Back in 1944, hatchet murder was front page news

To be murdered in Spokane is no great distinction. Homicide in the Lilac City has been rather regular throughout the town’s history. But a hatchet murder in Spokane, ah, now that is rare. And a bloody hatcheting with total victims that one-upped Lizzie Borden has only happened a single time in Spokane history.

If you drive on Sprague Avenue between Spokane and the Spokane Valley, you pass by the site of this gruesome event, described as the “Massacre at the Dillons” on the cover of the Official Detective Magazine June 1944. The Spokesman-Review called the deed a hatchet slaying on the Jan. 21, 1944, front page.

Whatever the description, someone chopped up four people at 1806 E. Sprague Ave., in a small apartment next door to the Rainbow Tavern. The tavern proudly sells cheer by the glass to this day and is the place where the hatchet story began, although the Rainbow Tavern moved from the corner to the middle of the block sometime during the last 60 years

T.P Dillon and his wife, Flora, owned a sign painting shop next to the tavern and lived in the small apartment in the back of the store. The Dillons joined in one of those Friday afternoon parties that so often come together in various saloons at the end of the work week. Predictably, the party went on until closing time which was midnight by Spokane law back in 1944.

The Rainbow bartender said the revelers purchased a quantity of beer and left to continue the party at the Dillons’ apartment next door.

The following morning, a man stumbled into the bar. The bartender offered him a beer. The customer could not speak. The bartender recognized the silent man as an employee at Dillon’s sign shop, Arthur Decker Brown.

Finally, Brown found his voice and implored the bartender to, “Go next door – around the back – see if you saw what I saw. It’s a massacre at the Dillons.”

The bartender did as asked. He returned white-faced and called the police.

Shortly, two of Spokane’s finest arrived and were led to the back door of the apartment by the bartender and the Dillon employee.

Four fully dressed persons had been reshaped with a bloody hatchet that was later found about 15 feet from the back door of the apartment.

At the crime scene, the cops found that two of the victims still had a pulse. The duo were transported to the hospital where one of the two later died.

The police had several suspects with motives, kind of like an Agatha Christie plot, and they all seemed guilty:

One of the victims, a 22-year-old woman named Jane Staples, was married to 55-year-old Charles Staples who stated he did not know where his wife was that night. However, when the police located him, Staples had blood on his shoes but claimed it was from a nosebleed. He declared that he knew his wife had recently cheated on him with at least three men. The newspaper reported that, although the husband was employed by the Armours Meat Packing plant, “Staples did not work in the killing department.” Prosecutor Leslie Carroll reported that in the 1930s, Mr. Staples was active in Communist circles. This had to be the guy?

Arthur Decker Brown was an employee of the Dillons at the sign painting store in front of the crime scene. He quit his job that fateful Friday afternoon due to differences with the Dillons. It wouldn’t be the first time that a disgruntled employee got back at his employers. And of course, Brown was the person who reported the crime which always makes for a good suspect. The police detectives held Brown, because when the police arrived on the snow-covered scene outside the apartment, only Brown’s footprints and the bartender’s footprints led to the door of the apartment where the chopping occurred. Brown admitted that his footprints were there first.

The only hatchet victim who lived, Frank S. Winnett, muttered the name “Ed Quentin” as he was being rushed to the hospital. Quentin showed up at the prosecutor’s office a couple of days after crime day. He claimed that he and the hospitalized victim worked at a defense plant in Ephrata and the police were told by Quentin that “Winnett disliked women, although he went on drinking sprees.” Probably both of these seemed like bizarre behavior in 1944. Was Quentin suggesting that the victim was sufficiently deranged to chop himself up with a hatchet? Quentin probably wished that the semiconscious victim would quit muttering his name.

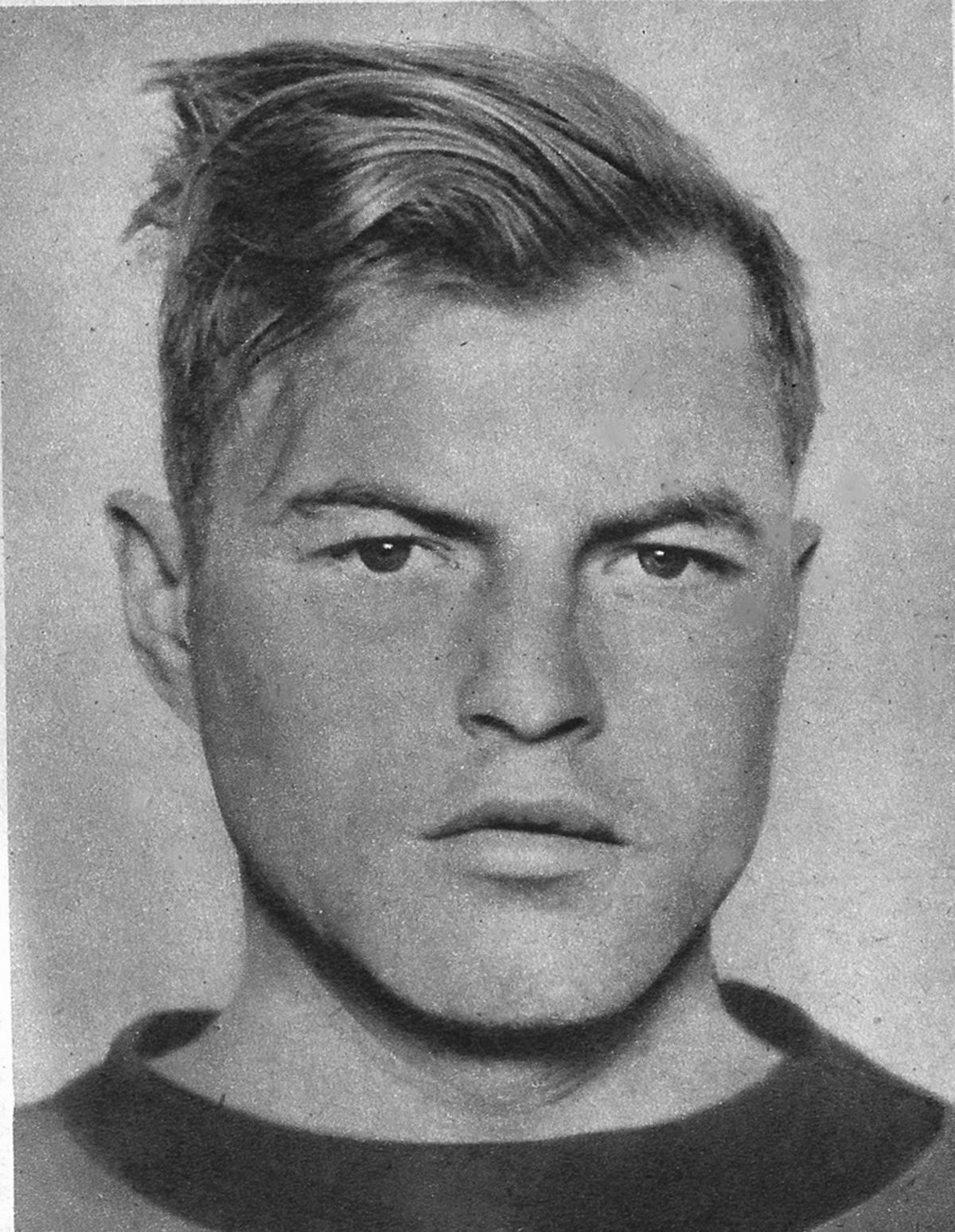

Then there was Whitey Clark, who walked with a limp. He was drinking with the crowd and took over chef duties to fry up an early breakfast for the late-night party at the Dillons’ apartment. He admitted to using a hatchet to split some kindling to fire up the wood cook stove in the Dillon’s kitchen. Clark said the group ate his breakfast of bacon and eggs. He claimed to have departed from the premises at “half-past two” before the party ended.

This mystery was not solved by Miss Marple or Sherlock Holmes working toward the identity of the murderer using deductions built on deductions. No, it was the 1944 version of C.S.I. that came into play. Forensic files were alive in the local Police Department before anyone had a television in Spokane.

To be specific, the coroner determined that the victims had been killed at 5 a.m. Further internal (and I mean internal) investigation determined that the victims had eaten their eggs and bacon 30 minutes before death, at approximately 4:30 a.m. Oops. Clark claimed he had cooked and eaten breakfast with the soon-to-be-murdered and had left the place by “half-past two.” The bacon and eggs had digested a half an hour when the murders occurred at 5 a.m. Whitey was a liar, if not a murderer.

The police rounded up all The Spokesman-Review newspaper delivery boys in the area and had them observe a line-up that included Clark. They all picked him out and reported that he had red stuff on his shirt while walking down Sprague Avenue as they delivered their early morning routes on the day of the hatchet work.

The police started a lengthy all-night interrogation of Clark, probably rigorous questioning. Back in the 1940s, the only “Miranda” that police talked about came with the first name Carmen.

Meanwhile the cops had found Clark’s bloody clothing at a friend’s house. Whitey Clark was presented with his bloody clothing and confronted with the bacon-and-eggs contradiction. He signed a confession.

Clark said that he and Mr. Dillon had a confrontation while the others dozed off at the party. He and Dillon reportedly had several quarrels during the evening over Clark’s advances on Flora Dillon. Clark said Dillon pulled out a gun and that inspired him to administer the hatchet treatment upon Mr. Dillon. Then he chopped away at the others as each of them awakened in order to eliminate witnesses.

They all died for Whitey’s hope of romance with Mrs. Dillon.

Woodrow Wilson “Whitey” Clark was convicted of first-degree murder and paid the ultimate price.