Microchip revamp

‘Printed semiconductors’ would be cheap, flexible and chock-full of information

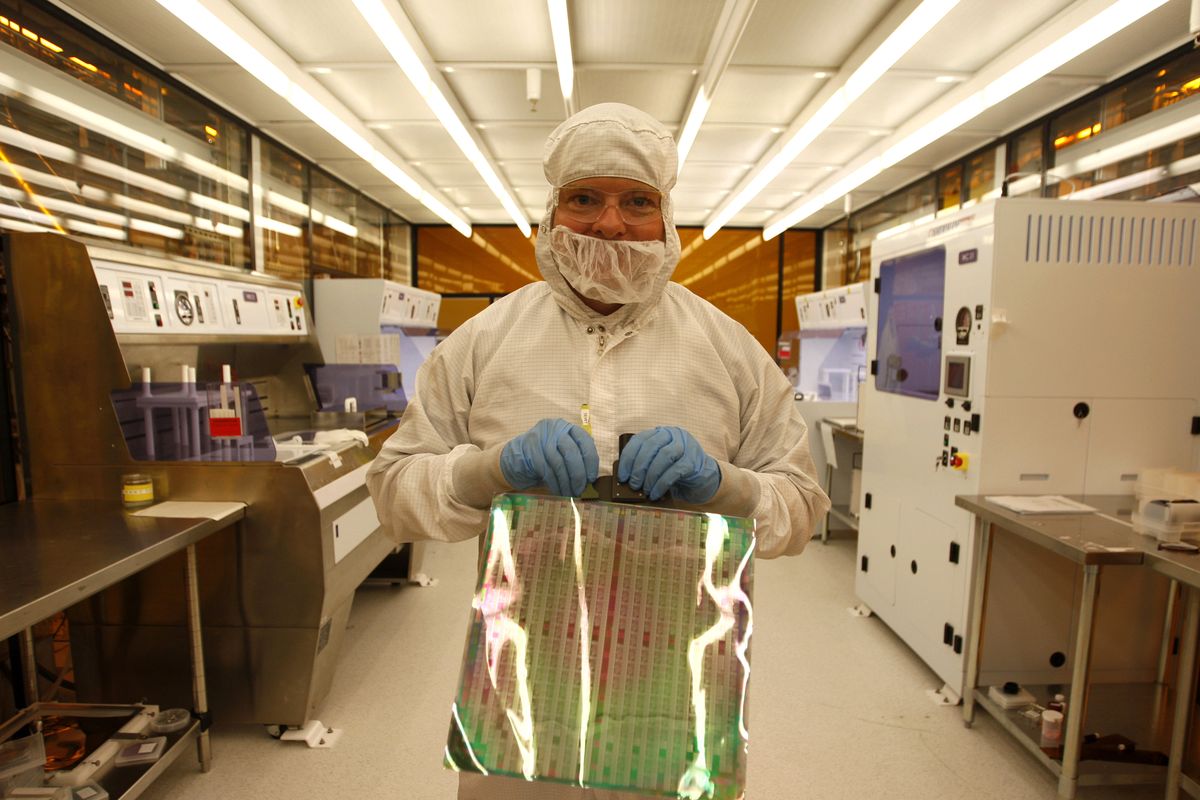

Michael Kocisis, a senior print engineer at Kovio, holds a steel sheet imprinted with silicon ink in the clean room at Kovio in Milpitas, Calif. Kovio is developing printed semiconductors.McClatchy Tribune photos (McClatchy Tribune photos / The Spokesman-Review)

SAN JOSE, Calif. – Until now, creating the microchips that power all of our electronic gadgets has been a laborious, complex and time-consuming process costing billions of dollars.

But if a Milpitas, Calif.-based startup succeeds, making them could be as easy as printing a piece of paper.

And that could open up a huge market for “printed semiconductors,” which would contain an enormous amount of data but would be cheap enough to slap on thousands of products.

Privately held Kovio hopes to launch in a matter of weeks what is believed to be the world’s first manufacturing plant for printed semiconductors. By using inkjet and other types of printers, the company plans to make radio frequency identification devices – so-called RFID tags. Such tags traditionally contain microchips, but are so expensive now their use has been relatively limited.

If Kovio succeeds in keeping the price of the devices low, according to its executives and others familiar with the company, it could herald a new era for consumers and the chip business. Imagine going to the grocery store and being able to find out what wine works best with your favorite chicken recipe.

“If Kovio can pull that off, it’s an enormous opportunity,” said Carl Taussig, director of Hewlett-Packard’s Information Surfaces Lab, which is exploring a different but related technology. “It’s going to revolutionize that whole industry.”

What Kovio, HP and a growing list of other companies are working on falls under the broad category of printed electronics, which includes such things as solar panels, disposable blood glucose sensors and gadgets for displaying various types of information.

Using an imprinting method it has developed, for example, Taussig’s group at HP is trying to make flexible electronic displays that can fold like a newspaper or bend around a building. Research firm IDTechEx predicts the printed electronics market will surge from less than $2 billion this year to about $57 billion in 2019.

The niche Kovio is exploring – offering printed semiconductors featuring memory and logic capabilities like those on traditional chips – now is only about $10 million a year, according to Raghu Das, IDTechEx’s CEO. But IDTechEx expects printed semiconductor sales to hit $100 million by 2012, and Das expects Kovio to be the first to begin manufacturing them.

Kovio’s CEO, Amir Mashkoori, who has labored for 28 years in the chip industry, believes the market one day will be much bigger than that. He sees printed semiconductors eventually becoming a multibillion-dollar business.

Founded in 2001 by scientists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Kovio initially focused on making flexible displays, but it switched to printed semiconductors, believing those devices hold greater promise.

By using silicon-based ink, the company says it can print RFID tags on soup cans, textiles and a range of other surfaces. While Kovio’s printed semiconductors aren’t nearly as complex and powerful as many other traditional chips, particularly the brainy microprocessors made by such companies as Intel, Mashkoori said his tags take far less time to make. They also don’t require as many chemicals to manufacture, making them a greener alternative, he added.

But the biggest selling point is their cost. Mashkoori said Kovio should be able to produce them for about 5 cents a tag – perhaps even for as little as a penny – making them appealing, he says, to a broad assortment of businesses.