Textbook case for e-readers

Students testing Kindles give lukewarm response

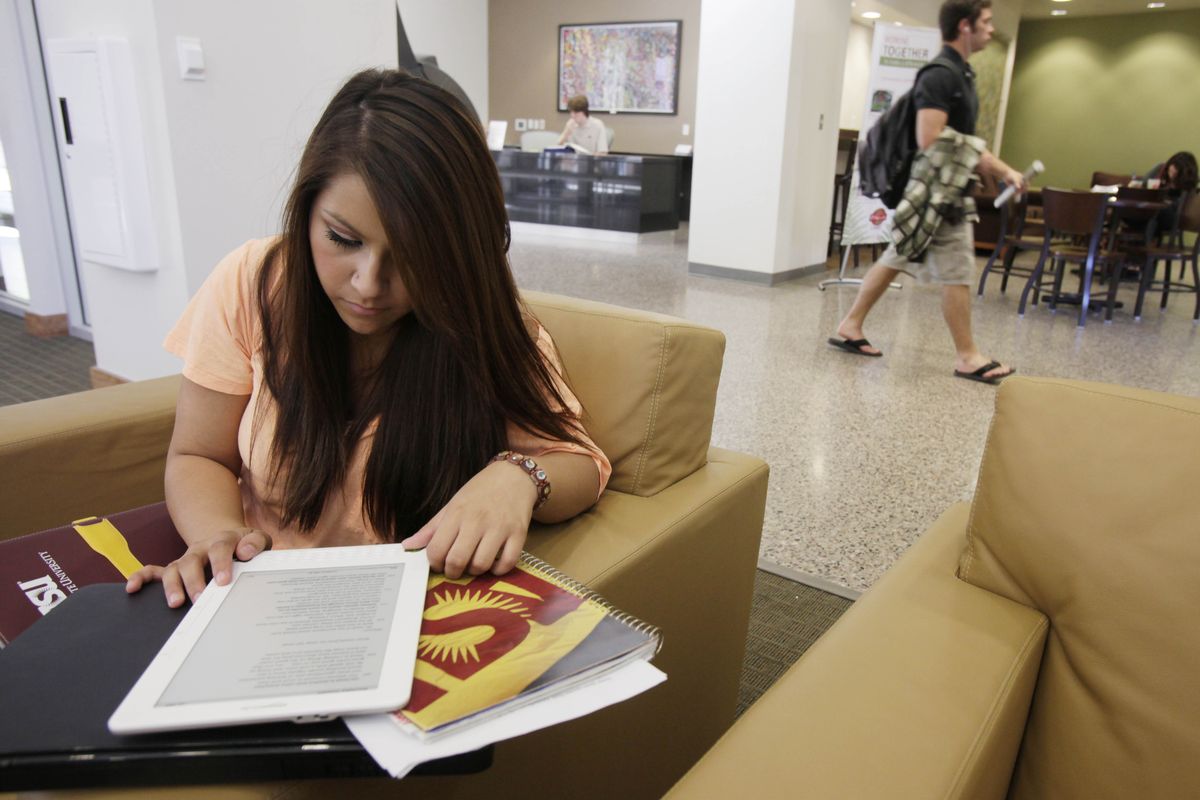

SEATTLE – It’s an experiment that has made back-to-school a little easier on the back: Amazon.com gave more than 200 college students its Kindle e-reading device this fall, loaded with digital versions of their textbooks.

But some students are finding they miss the decidedly low-tech conveniences of paper – highlighting, flagging pages with sticky notes and scribbling in the margins.

“I like the aspect of writing something down on paper and having it be so easy and just kind of writing whatever comes to my mind,” says Claire Becerra, a freshman at Arizona State University.

Becerra tried typing notes on the Kindle’s small keyboard, but when she went back to reread them she found they were laden with typos and didn’t make sense. After a month, she says she takes far fewer notes and relies on the Kindle’s highlighter tool instead.

Amazon wants to adapt the Kindle to academia, where it could reduce the notoriously high cost of textbooks. The Kindle DX, with a larger screen than the regular model, costs $489, but digital books can cost less than half what physical ones do.

While it might be the future of textbooks, Amazon or any other e-reader company has a long way to go to make it happen – even for a technology-saturated generation that should be more receptive to the shift.

When the Associated Press hit five of the test campuses to ask students how they felt about the Kindle, the responses were lukewarm.

Most said they liked the prospect of having anytime access to a semester’s worth of reading on the Kindle, which can wirelessly download books or get material by being plugged into a PC.

But several disliked taking notes on a keyboard with Tic-Tac-sized keys that sits under a 9.7-inch screen.

Students can also highlight text or bookmark pages – the digital equivalent of dog-earing – then look at those excerpts and links on separate screens.

Madeline Kraizel, a freshman at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, has amassed three Kindle pages of bookmarks for her chemistry textbook. That’s getting unwieldy, and she isn’t sure whether there’s a better way to organize them.

Another drawback: The Kindle doesn’t show page numbers. Because text can be made bigger or smaller, a turn of the virtual page doesn’t necessarily correspond to the printed book. Instead, Kindle uses “location” markers.

That threw Kraizel and one of her classmates, Hun Jae Lee. Lee, 19, says professors had to give Kindle-equipped students a few words to search for. Eventually, they started referring to both Kindle locations and textbook page numbers.

Other students struggled when professors had them read documents in PDF format, which doesn’t show up well on the Kindle. Users can’t zoom in or make notes on them, and diagrams sometimes get separated from notes explaining them.

John Sherman, a first-year MBA student at the University of Virginia, says he can read some case studies on the Kindle but still needs to print others.

“For the cases that require a lot of calculations, I find paper cases to be better,” says Sherman, 31. “For me, it helps to scribble my thoughts in the margins.”

Todd Schiller, 22, a student in the University of Washington’s doctorate program in computer science, says he prefers the visual cues of a paper textbook to the “tunnel vision” that today’s e-reading promotes.

Opening two big textbook pages puts the section he’s reading into context: Seeing how many pages remain in a chapter or the book helps him understand how far along he is in the author’s plot or argument.

The dozen or so students interviewed by the AP had compliments for the Kindle, too.

Most like how light the device is – just over a pound – and many would be willing to overlook technical hassles if it meant not having to carry any books. Most still had to buy and carry textbooks for non-Kindle classes this fall.

Students were also impressed with the “electronic ink” screen, which Amazon touts as far easier on the eyes than reading off a computer monitor.