Parade change averted blast

Harpham wasn’t close enough to detonate bomb

The lingering mystery of why the bomb left along the planned route of the Martin Luther King Jr. Unity March didn’t explode finally has an answer: The remote triggering device never got close enough to detonate it.

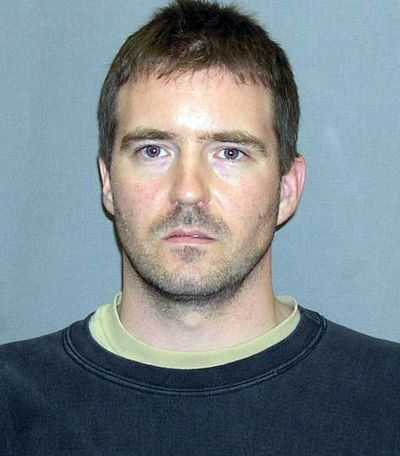

A federal source close to the investigation confirmed late Tuesday – after court files were unsealed in the case against Kevin W. Harpham – that the actions of two city contract workers and Spokane police Sgts. Jason Hartman and Eric Olsen likely averted an explosion that could have killed or severely injured several people.

Harpham “was in the parade,” the source said. “It was the good work of the Spokane Police Department in moving the parade that removed an opportunity to detonate the device.”

Harpham, 37, has pleaded guilty to attempted use of a weapon of mass destruction and targeting minorities with the bomb he admittedly built using quarter-ounce fishing weights laced with rat poison. He placed the bomb on the northeast corner of Main Avenue and Washington Street, originally along the march’s route.

According to the case file, it was the fishing sinkers that sank Harpham.

After learning of the bomb’s contents soon after Jan. 17, FBI agents did a records search of all 72 Wal-Mart stores in the Northwest trying to find any large purchases of quarter-ounce fishing weights. An agent on Feb. 12 discovered three such purchases at one Wal-Mart in Colville. Two of those purchases were made with cash and one was made using a debit card owned by Harpham.

“The whole thing went through a sequence of events,” the federal source said, indicating that Harpham was the prime suspect about a month prior to his arrest. “But that was the genesis. It started with the lead weights and the debit card.”

Two days later, federal investigators knew where Harpham lived. While the records don’t indicate when the surveillance began, one notation indicates that a federal agent was watching Harpham on Feb. 19 as he walked with “at least two dogs” at his 10-acre property in a remote area near Addy, Wash.

“He is the prototypical lone wolf,” said the source, referring to domestic terrorists who work independent of any organized movement or group.

Between Feb. 25 and March 4, agents identified 1,139 postings by Harpham on the racist website Vanguard News Network under the user name “Joe Snuffy.”

Then on Feb. 28, investigators obtained Harpham’s DNA profile from samples he provided while serving in the U.S. Army from 1996 to 1999. Within days, the FBI had DNA linking Harpham to the strap of the backpack that contained the bomb found just prior to the march.

The first week of March, agents from all over the country began gathering at a downtown Spokane hotel as search and arrest warrants for Harpham were signed on March 8. The next morning, the agents geared up and headed north.

On the morning of March 9, Harpham drove away from his home at about 8:45 a.m. and noticed a flagger who stopped him and asked him what direction he was driving, according to court records filed by defense attorneys Roger Peven, Kimberly Deater and Kailey Moran.

After directing Harpham to drive across the bridge, a van on the opposite side pulled forward and blocked the road. Harpham then attempted to drive backwards off the bridge.

“Without warning, the bucket, of what appeared to be a back-hoe, came down with full force on the back of Mr. Harpham’s car, breaking out the rear window on impact,” defense attorneys wrote. “The back-hoe then began pushing the car, with Mr. Harpham in it, forward across the bridge and toward the van.

“As this was happening, the van doors opened releasing approximately a dozen men dressed in camouflage and armed with assault rifles.”

Harpham asked what was going on and he was informed that he was under arrest for the bomb found along the march’s planned route. As FBI special agents Joe Cleary and Ryan Butler drove Harpham to the Stevens County Jail, Harpham asked how long the FBI had known about him.

Cleary responded that they just met. “Harpham then said, ‘No, how long have you known about me?’ Agent Cleary did not respond. Mr. Harpham then muttered, ‘About two months,’ ” the defense attorneys wrote.

Searches found indications that Harpham had built a second “practice” bomb that he detonated in a gravel pit. They found how-to books on bomb making and the biography of Timothy McVeigh, who orchestrated the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing.

Harpham faces between 27 and 32 years at his sentencing, scheduled for Nov. 30. On Monday, defense attorneys wrote a motion seeking leniency from U.S. District Court Judge Justin Quackenbush during the upcoming sentencing.

“Mr. Harpham, who has lived an exemplary life until recent events, who has no criminal history, who has been a good son, brother, neighbor, soldier and friend deserves to have this Court take into account the good works that account for the majority of his life,” Peven, Deater and Moran wrote. “He accepts responsibility for his crime and a sentence of 27 years is just punishment for his misdeeds.”

Harpham’s mother, Lana Harpham, wrote in a letter to the judge that her son dropped out of high school his senior year but later earned his GED as well as an associate degree in applied science.

“I know how and what he is,” Lana Harpham wrote. “I am very proud to say he is my son. I would want no other.”

Harpham’s sister, Carmen Harpham, also wrote to the judge saying she had never seen “Kevin be anything but gentle with both people and animals.”

The letters describe family members attempting to understand how the Kevin Harpham they knew – who went great lengths to care for his father and neighbor – would leave a bomb in downtown Spokane.

“There are many things that I have heard over the past nine months regarding my brother’s actions that I cannot explain,” Carmen Harpham wrote. “While I know we do not share a common philosophy about race, I am puzzled at what brought my brother to this point in his life.”