US Reps. expect deeper look at NJ derailment

CLARKSBORO, N.J. (AP) — Federal regulations require inspections of rail bridges and other infrastructure and reports on accidents, but leave it to freight railroad owners to do the work themselves.

After a derailment that released thousands of gallons of a hazardous chemical into the air last week in New Jersey, forcing dozens of households to be evacuated, a congressman said Wednesday that it is time to end what he called “a culture of self-regulation” for the industry.

“We’ve got to come up with a sensible set of regulations,” U.S. Rep. Rob Andrews, a Democrat whose district includes Paulsboro, the site of the derailment, told The Associated Press on Wednesday.

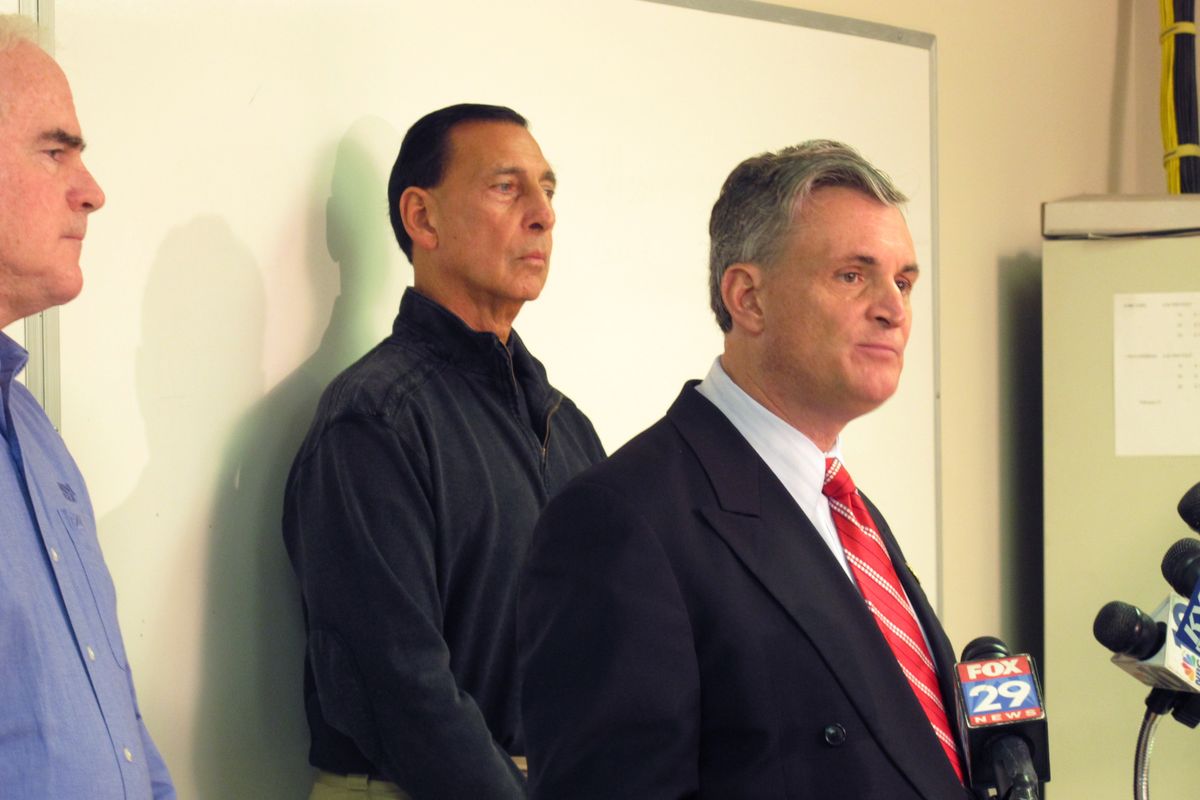

Andrews, and Republican Reps. Pat Meehan of Pennsylvania and Frank LoBiondo of New Jersey, met Thursday at a command center in nearby Clarksboro with officials working on the accident response. The congressmen said they expect to hold hearings looking at both the causes of the derailment and the response to it.

An industry spokeswoman said the rail companies have specific requirements from the Federal Railroad Administration and other regulators, and that it makes sense for companies to conduct their own inspections and report on their own accidents.

“We are the only mode of transportation that owns, maintains and repairs its own infrastructure,” said Holly Arthur, a spokeswoman for the Association of American Railroads. “It is in the railroad’s interest to ensure that infrastructure is world-class.”

Many standards for rail operation, she said, are laid out in federal regulations and the FRA has the power to go after noncompliant railroads with civil penalties. She said that the industry is required by law to haul hazardous chemicals and that leaks are rare.

Last Friday, seven cars on an 84-car train derailed on or near a swivel-style bridge over Mantua Creek in Paulsboro. A tanker car carrying vinyl chloride, a gas used to make PVC plastic, was ruptured, sending thousands of gallons of the chemical into the atmosphere.

Dozens of people who live or work nearby were checked out at an emergency room and none showed serious health effects. Since then, more than 200 homes in the industrial town across the Delaware River from Philadelphia International Airport have been evacuated. Vinyl chloride levels have intermittently risen high enough that workers trying to recover the remaining chemical, which naturally hardened into a solid, have been pulled off the scene.

By Wednesday, Andrews said, the efforts to recover the chemical were moving ahead and a barge was in place to haul the tanker cars away.

Meanwhile, Paulsboro residents are growing frustrated. At a raucous meeting with officials Wednesday night, hundreds showed up with concerns that they were getting inconsistent information about whether the air was safe to breathe and when everyone could return to their homes.

Andrews said one area he wants to explore is the structure of the government’s response team, which includes several federal, state and local agencies coordinated by the U.S. Coast Guard.

“When everyone’s in charge,” he said, “no one’s in charge.”

He said that for future problems like this, perhaps one specific agency should be given broad powers the way the Federal Emergency Management Agency is after natural disasters.

“I’m certainly aware of the fact that people in the community have had too much misinformation and too many false deadlines,” he said.

Meehan said that’s one of the issues he wants to explore after the accident investigation is complete.

The National Transportation Safety Board is investigating the crash and has not ruled on its cause.

But board chairman Deborah Hersman has laid out how the bridge, originally built in 1873, had problems in the weeks leading up to the derailment. When the train pulled up to the swivel-style structure on Friday, the signal light was red. She said that was an indication that all four locking mechanisms on the bridge were not secured. But after the train’s conductor looked at the structure, he received permission from a dispatcher several miles away to cross even under a red light.

Hersman was careful to say that the train crew members followed their training.

But Andrews said that guidance may have been incorrect.

He said it’s a similar story with other railroad matters. Conrail and the FRA may have been following their protocol, he said, but the rules themselves could be flawed.

There was a derailment on the same bridge in August 2009, but from the publicly available documents, it’s hard to tell whether it was similar to last week’s.

Consolidated Rail Corp. and Norfolk-Southern, at the time co-owners of the line, each filed the requisite one-page form on the accident, which caused $480,000 in damage when nine coal cars derailed. According to a code on the form the cause was found to be “bridge misalignment.”

Each form contained just one sentence of written description of what happened.

Neither the FRA nor the NTSB investigated the accident — and neither was required to do so.

Railroad experts agree that there are relatively few swivel-type bridges remaining out of an estimated 75,000 to 100,000 freight rail bridges across the country.

But FRA spokesman Kevin Thompson said the agency does not keep a complete inventory of bridges, either.

Andrews said he believes that an independent agency should have a greater role in rail safety, especially for trains carrying hazardous materials that, if spilled, can jeopardize public health.

He said it’s Congress that needs to force such changes.

Bob Comer, an Ohio man who has investigated 300 train accidents, most on his own and some as an expert witness for plaintiff’s lawyers in lawsuits, said the problems run deep.

“All the way back to 1825 when the railroad industry started in the United States,” he said, “they have put money ahead of safety.”

___

Follow Mulvihill at http://www.twitter.com/geoffmulvihill