Success with 10-year bond drives Spokane levy for streets

If there’s one thing Jim West would want to be remembered for, it’s probably pavement.

In his race to become Spokane’s mayor in 2003, West promised to remake the city’s pockmarked streets into ribbons of smooth asphalt.

“Inaction is not an alternative,” he said at the time.

Voters agreed, put him in the mayor’s office and followed his lead in passing a 10-year, $117 million street bond. West made the street project the cornerstone of his first year in office.

Those bond projects are wrapping up. The trenches on Monroe Street between Eighth and 17th avenues were dug using the last dollars of the bond. When the concrete is poured later this month, Monroe will be among the last stretches of the bond’s work on 110 miles of streets – enough road to connect Spokane with Lewiston, all within city limits.

City officials tout the project as an unmitigated success. It was finished on time, they say, and came in under budget. Excess funds went to Monroe and three other projects that weren’t originally part of the plan.

Now the city wants another shot at re-creating Spokane’s streets, and voters have the chance to approve a broader investment this fall.

Without changing the property tax rate related to street maintenance, the city has a plan to extend work another 20 years while paying off the $84 million of debt left on the 2004 bond. The ballot measure would levy about $5 million a year for arterial street work and, by combining it with repairs to water lines and stormwater drainage systems, the city expects to bring in $25 million a year for integrated projects.

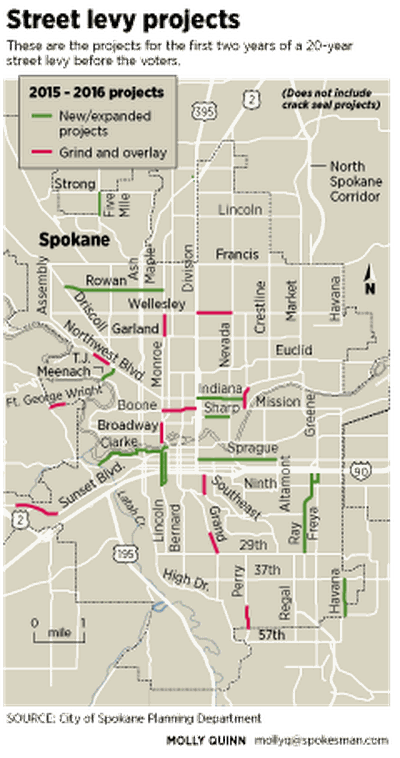

The first two years of projects under the levy already are planned, including a rebuild of East Sprague Avenue, South Ray Street and West Rowan Avenue.

“People always want more services without paying any more money,” City Council President Ben Stuckart said. “That doesn’t happen very often. But this is an example of it actually happening.”

‘Golden Gate Bridge mentality’

Think about the year 2034, said Gavin Cooley, the city’s chief financial officer. If the levy passes, that’ll be the next year Spokane voters will be asked to consider streets. All of the city’s 266 miles of arterials will be fixed.

“The notion of driving on streets with potholes will be absolutely a thing of the past,” Cooley said.

“Don’t worry. We’ll always have potholes to fix,” said Mayor David Condon, when asked if Spokane’s storied pothole reputation was at risk. “The reality is this allows us to focus on maintenance. I jokingly say we should start on one side of the city for crack seal, go across the city, and then turn around and go back. It’s the Golden Gate Bridge mentality. As soon as you’re done painting it, you turn around and go the other way.”

The idea of perpetual maintenance is central to the ballot measure. It’s why City Hall is going for a levy and not a bond, which is a city-issued loan. Street work always is needed. Going into debt for something that needs an ongoing source of funding is inappropriate, Condon said.

The argument to use a levy instead of a bond is simple, said Rick Romero, the city’s utilities director. Bonds are good for fixing parks, building libraries and other one-time projects, but levies are good for ongoing needs, such as police, fire and, Romero argues, streets.

Street work paid for with the 2004 bond is basically complete, but there are still 16 years of payment left on the bond because debt was sold in three increments: 2004, 2007 and 2010, each with 20-year terms. The debt is paid for with a property tax of 57 cents for every $1,000 of assessed property value. That’s $74 a year on a $130,000 house, the median home value in Spokane.

At Romero’s urging, the city found a way to restructure the debt while keeping the rate the same. If the levy passes, about half of the 57 cents per $1,000 of property would pay off the old debt, and the other half would pay for new projects. In 2015, the levy would bring in about $4 million. By the time it was retired in 2034, it would generate $8 million in funding.

Romero took it one step further. The city plans to combine the annual money coming in through the levy with $5 million from the utilities department. That approximate $10 million will be used to bring in matching state and federal grants, which typically draw two or three times the local match.

If the levy passes, Romero said, the city can expect up to $25 million a year in integrated projects. Over 20 years, that comes to about $500 million.

“It’s innovative. We’re being self-sufficient,” Councilwoman Amber Waldref said. “Having a local match shows the state and federal government that we’re serious.”

Streets as park land

Just two years before West’s successful street bond in 2004, a smaller, $50 million street bond measure was thumped in the polls. Just 44 percent of voters approved, when 60 percent approval was needed for passage.

Cooley said some at City Hall were surprised West asked voters for an even larger bond.

“He said, ‘Look, the reason it was voted down was because citizens didn’t think it would make a difference. They’re not concerned about the dollar amount. The citizens want this thing handled.’ ”

Others, including Condon, said West’s plan was so specific and prescriptive that it built trust with citizens as well as built roads.

“It laid it all out. These are the streets we’re going to do. This is when we’re going to do it,” Romero said. “They had to have that. What we’re trying to do in terms of integration wouldn’t have worked in 2004. We weren’t ready as an organization. We weren’t ready for it in terms of trust.”

The successful completion of the bond projects helped build trust, Romero said. But as West knew early on, he needed the public to participate if it was to succeed.

“There was a huge amount of citizen engagement,” Condon said.

At the outset, a board called the Citizen Street Advisory Committee was created to oversee the projects. Its scope was limited, but every month for the past 10 years, its seven members have met to check how the money was being spent.

In July, the City Council passed an ordinance creating a new, expanded oversight process. One difference with the new group, which is a Plan Commission subcommittee, is it falls under the City Council’s purview, not the mayor’s.

More importantly, the group will be involved in levy projects from the earliest design phases and will oversee more than project dollars. The ordinance recommends that the subcommittee, which will be led by Plan Commission Vice President Brian McClatchey, draw its members from the city’s Bicycle Advisory Board, Spokane Regional Transportation Council, disabled communities, Spokane Regional Health District, Spokane Transit Authority, Spokane Public Schools and Greater Spokane Incorporated, among others.

“The street bond was limited to just paving curb to curb. The new levy actually looks at the whole street. From sidewalk to sidewalk and down underneath it,” said Councilwoman Candace Mumm, who sponsored the ordinance. “Think of streets as park land. It’s public land. This is public space. We want to see what else we can do with it.”

Lukewarm to enthusiastic

Supporters of the levy have raised about $48,000 so far, according to the state Public Disclosure Commission. The money was raised by a campaign that also supports the Riverfront Park bond, which is on November’s ballot as well.

The biggest donors include CPM Development Corp., Visit Spokane and the Cowles Co., which owns The Spokesman-Review. Each gave $5,000. Individual donors include Downtown Spokane Partnership President Mark Richard, Inlander Publisher Ted McGregor, Councilman Jon Snyder and local businessman Larry Stone.

There’s no organized opposition to the levy, but it took some lobbying of council members before they agreed to put it on the ballot. All members now support the levy.

“I started out very lukewarm to the levy,” Snyder said. “I wondered how the money would be spent in an equitable way.”

After Mumm’s ordinance, he signed on.

As a pedestrian and bicycling advocate, Snyder said he’s been assured levy projects will keep different forms of transportation in mind.

“The people are really demanding it,” he said. “The subcommittee will demand it.”

Councilman Mike Allen sees the need for a levy in starker terms.

“The citizens have been asking for 30 years for a long-term street solution,” he said. “Now they have one in front of them. They just have to vote for it.”