Councilwoman Amber Waldref terms out at City Hall, returns to nonprofit work in northeast Spokane

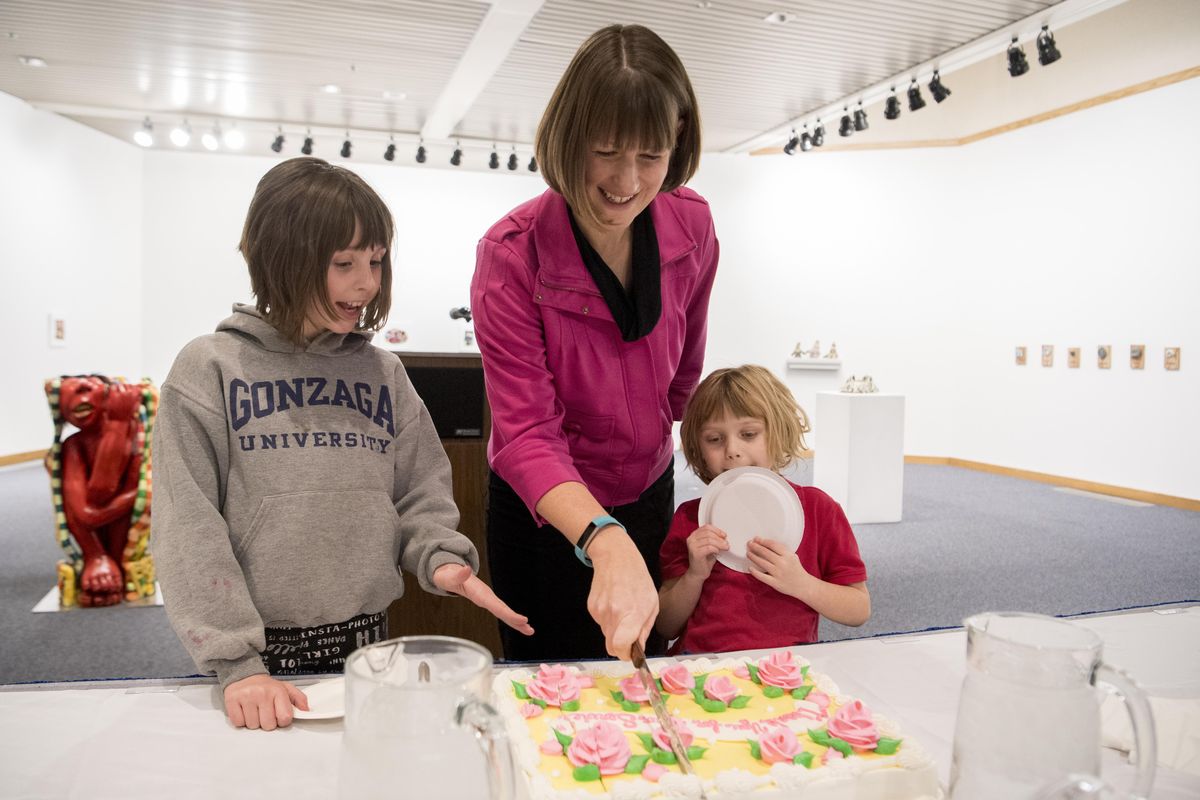

Amber Waldref, left, talks about her eight years as a member of the Spokane City Council on Monday, Dec. 18, 2017, at a reception before her final meeting as a sitting council member. (Jesse Tinsley / The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

Rita Waldref didn’t expect her daughter Amber to run for office.

“I thought the other daughter would,” said their mother with a laugh, referring to Waldref’s sister, Vanessa. George Waldref, Amber’s father, joked that they had to bribe Amber with a dollar to speak up in the classroom.

But run she did, with her mother taking on the role of campaign manager. She ran, and won. Eight years later, Amber Waldref has ended her eligible time at City Hall and is returning to serve, at least part-time, the northeast neighborhood where she was raised and cut her political teeth.

“We’ve put the building blocks in place for northeast,” Amber Waldref said, during an interview earlier this month. “I think it’s long overdue. We have plenty of building blocks in place, now we need to let them fly.”

Waldref, 40, plans to split her time working on behalf of Urbanova – a smart city public-private partnership based in the University District focused on improving public services – and working with the Northeast Community Center on The Zone, an initiative to improve education and battle poverty in some of Spokane’s poorest neighborhoods.

The councilwoman’s friends, colleagues and even some political rivals praised the longtime local lawmaker’s meticulous attention to detail and behind-the-scenes diplomacy. Most predicted future political positions for Waldref, a Spokane native who left town to attain degrees at Georgetown University and later Antioch University in Seattle, before returning to take positions at the Lands Council, where she served as development director before joining the City Council.

“Amber is very passionate about the quality-of-life issues,” said Spokane County Commissioner Al French, a Republican whose seat on the City Council went to Waldref in the 2009 election after he termed out of office.

“In my two years with her, she was the hardest-working, most conscientious council member,” said former Spokane City Council President Joe Shogan. “I think she’d make a great mayor for the city.”

Waldref’s foray into politics required some coaxing, however.

Sticking to the details: Buses and stormwater

Waldref’s decision to seek elected office came after giving birth to her first child, a daughter named Karolina, and working with volunteers in the Logan neighborhood, where she relocated with her husband, Tom Flanagan.

“At that point, I had never thought about running for office,” Waldref said. “It wasn’t until a couple friends-of-friends in the neighborhood said, ‘You need to start going to these Logan neighborhood meetings.’”

A second daughter, Nora, was born during Waldref’s first term in office.

Waldref worked with Karen Byrd, a longtime neighborhood resident and then a member of the city’s Plan Commission, to learn the ins and outs of city planning.

Speaking now, Waldref lauds the importance of local elected leaders looking toward the future. It’s not the new police officers in this year’s budget that are most exciting for her; it’s the addition of new city planners, who can help draft the documents for neighborhoods, like the ones that were written for Hillyard and the Hamilton corridor in northeast Spokane, that will have the most lasting effect on the future of the city, she said.

“We just have so much opportunity for development, and we say we want to grow in these infill areas,” Waldref said. “But until we do the work with those neighborhoods and identify the goals and put the tools in place to make it happen, nothing’s going to change. It’s going to be status quo.”

City Councilwoman Candace Mumm, who followed a similar path to Waldref’s as a neighborhood advocate in north Spokane and a member of the city’s Plan Commission before joining the City Council, said it’s rare to see a lawmaker with the breadth of knowledge and perspective her colleague brought to the office.

“She was able to look at issues from a global perspective as well, with her environmental background,” Mumm said. “She’s interested in protecting our river and our environment, while still supporting an urban core. That’s not something you find often in a person of her age, or someone who really hasn’t been in city government for a while.”

One of those projects is the planned opening in 2021 of a rapid Spokane Transit Authority route cutting through downtown Spokane, called the Central City Line. Waldref served as one of the city’s representatives on the STA governing board since 2009, pitching to voters a sales tax increase to fund the new service. The original proposal was narrowly rejected in April 2015, but a scaled-back measure passed in November 2016 with 55 percent of the vote.

“If transit can be frequent enough, and accessible enough, then it gives people a true option to leave their vehicle at home or not need to have one,” Waldref said. “I think that’s really important for our growth goals.”

Mumm, who serves with Waldref on the STA board, praised her work on the project.

“I don’t think we’d have a Central City Line coming if it wasn’t for Amber Waldref,” Mumm said. “That project is going to be transformational for the city.”

Coming from the Lands Council, where she served as water watch coordinator in the mid-2000s, Waldref also leapt at the chance to work with Mayor David Condon’s administration in developing the new clean water plan that revised downward the size of massive subterranean storage tanks that trap stormwater from overflowing into the Spokane River and meet standards established by the Washington Department of Ecology and the Environmental Protection Agency.

Waldref described herself as “kind of a geek” about pollution levels.

“I was very careful about looking at all the data that we had, and it showed that even if you had an overflow on every tank once, you would still meet the guideline,” Waldref said. “I hope that continues. I hope that we did our math right. Time will tell with climate change whether or not we’ll see more rain events.”

Rick Romero, the city’s utility director who developed the revised plan, called Waldref “a huge asset to the city.”

“The two best words I can think to describe Amber is just positive energy,” Romero said.

Waldref said she tapped into that positive energy in an attempt to get the mayor’s office and council talking again after the exit of embattled former Police Chief Frank Straub tore a gash between the two branches of government.

Repairing for the future

Waldref called the summer of 2016 one of the most stressful of her life.

A report was released implicating members of Condon’s cabinet in the delayed release of records detailing a sexual harassment claim against Straub by Monique Cotton, a civilian employee in the department. City Council President Ben Stuckart called for those officials to resign, while Condon denied the handling of records was politically motivated and settled an ethics complaint charging he’d lied about the reasoning for Straub’s dismissal in a news release announcing the separation.

“I think a lot of trust was broken,” Waldref said. “I think the council has to trust in the administration making good (human resources) decisions. We have no control over that.”

Since that summer, Waldref said she’s been working with Romero and others in the administration to find common ground, beginning with priorities for economic investment and branching out from there. The result is a document, approved with the budget last year, that lays out nearly $52 million in investments while also detailing policy priorities jointly shared by the council and Condon.

The document is what Gavin Cooley, a financial adviser who has served under five Spokane mayors, calls “inside baseball” that most citizens won’t recognize unless the branches of government are at odds with each other. But he said the work is indicative of a more harmonious City Hall that he said developed with Waldref’s guidance.

“I think if you polled every member of the cabinet, they’d have really good things to say about Amber,” Cooley said. “She puts in a lot of time, and effort, and dedication.”

“I think it’s a legacy she’s left the city, how important it is to work together,” Cooley added.

Waldref hopes it’s more than just the ethic that created the document, but also the goals outlined within that continue to shape the city after she’s left. The councilwoman said she’s been asking for an overarching plan document ever since taking her first oath in 2009.

“We need to have a scorecard for our community,” Waldref said. “We need to measure our success.”

What’s next

Waldref’s parents still live in the same house where the couple moved a month after she was born, in the Logan neighborhood. Longtime residents are likely to see her jogging through the neighborhoods of northeast Spokane, where she intends to continue her work in the nonprofit sector this year.

“If we can address stabilizing families, and housing issues, I think that’s the next huge issue, and I’ve only touched the surface of that over the last four years,” Waldref said.

That includes work on a foreclosure ordinance intended to foster redevelopment of so-called “zombie” properties, which have been repossessed by banks but sit vacant. Waldref is in the process of handing off work on that issue to colleague Karen Stratton.

Waldref’s family and friends expect the councilwoman to throw herself into her nonprofit work, but see a political future for her as well.

“I think it’s in her blood,” Rita Waldref, her mother, said.

Shogan expects that, too.

“I look forward to her re-entering public life,” the former council president said.

French, the Republican county commissioner, said he too envisioned a run for some future elected office at City Hall.

“She enjoys working with the community,” French said. “It’s a challenge to work toward all that knowledge, and then walk away from it.”

For now, Waldref is content to recede into the background and enjoy some Monday nights with her family for the first time in eight years.

“I really enjoyed doing it, but after eight years, I’m really looking forward to a little break,” she said.