Health district and charitable groups respond to hepatitis A outbreak

“Make sure you let them know they can get their second dose,” Heather Schleigh, director of the House of Charity, tells her front-desk staff before they make an intercom announcement.

It’s 8 a.m., and the House of Charity, a 185-bed downtown homeless shelter, is lively. People are finishing their breakfast and some are waiting for showers.

Others are listening to the intercom to come get their hepatitis A vaccine for free.

A team from the Spokane Regional Health District set up a mobile vaccination unit in the conference room at the front of the House of Charity on Tuesday, where people could stop by to get the first, second or third dose of the vaccine to prevent hepatitis A or B.

Spokane County has nine confirmed cases of hepatitis A, up from three cases reported in June. Some of these cases required hospitalization, and so far those people impacted by the spread of the infection are all experiencing homelessness.

“We’re trying to focus on our population,” Schleigh said. “And it’s tough because they are in survival mode, so stopping to think about that is not their first priority.”

The health district is partnering with several community organizations to provide vaccinations to prevent hepatitis A and B in the midst of a state-declared outbreak of hepatitis A last week, focusing on those organizations that serve free meals, including House of Charity, Women’s Hearth, Hope House and the Salvation Army.

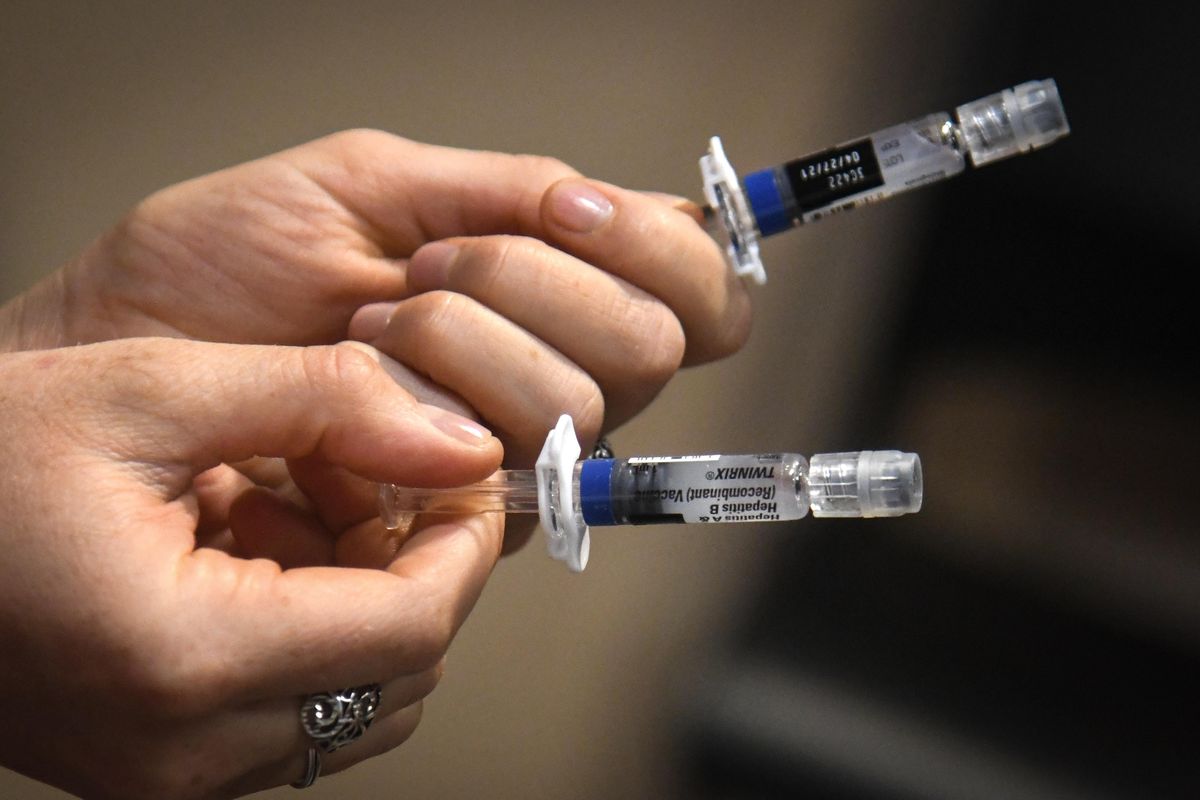

Spokane Regional Health District nurse Kira Lewis prepares hepatitis vaccinations Tuesday, Aug. 6, 2019, at the House of Charity in Spokane, Wash. (Dan Pelle / The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

Schleigh got the vaccine for herself when the health district first came in June, she said.

“I offered it to every employee of Catholic Charities … all of our volunteers, anyone could walk in off the street and get it,” Schleigh said.

Hepatitis A is a contagious acute illness that mainly impacts the liver. Symptoms include jaundice, abdominal pain, joint pain, nausea and vomiting as well as abnormal coloration of urine and stool.

The hepatitis A vaccine only began to be routinely administered to children in the U.S. in the early 2000s, so many adults older than 20 years old might not have the vaccination, unless they were traveling out of the country and got it – or have diligently kept up with their vaccinations at doctor appointments.

The infection is usually transmitted through fecal-oral contamination, which can occur when a person comes into contact – by touching, eating or drinking – with microscopic particles of contaminated fecal matter.

The infection spreads primarily due to lack of good sanitation services, which means it can disproportionately affect people experiencing homelessness.

“It’s primarily a sanitation issue, so we want to reiterate that this is not a cleanliness issue for this vulnerable population, it’s really an access to proper sanitation services issue,” said Anna Halloran, an epidemiologist at the Spokane County Health District.

Molly Kircher has been staying at the House of Charity for about six weeks, and on Tuesday morning she got her second dose of the hepatitis A vaccine. Health district staff were able to look up her vaccination records using the state’s immunization tracking system, and she figured out she needed the second dose.

Kircher religiously washes her hands, before and after meals, when she is at the House and not at the House, she explains, and even after putting her dirty clothes in a washer.

“It’s about not wanting to get sick,” she said, which is also why she got her second dose of the vaccine on Tuesday.

The city of Spokane installed a hand-washing station at the House of Charity in July as well as at the Salvation Army and outside City Hall in response to the outbreak. House of Charity also added an independent hand-washing sink outside of its laundry room.

“Access to hand-washing, particularly before eating, is extremely important,” Halloran said. “We want to make sure that everybody in our community has access to both preventive health care and sanitation service.”

There’s a wide spectrum of how the infection can affect a person’s health. For some people, hepatitis A could lead to a two-week period with little to no irritation. But for others, the illness could lead to hospitalization, a liver transplant or even death.

There is no cure for hepatitis A, and although it is not chronic, those who get infected have to wait it out.

Since the June outbreak in Spokane County, the health district has given 388 vaccinations, including both the hepatitis A vaccine and the hepatitis A and B combined vaccine. At the House of Charity alone, health district staff have given 60 vaccinations in the last two months.

Schleigh and her team have worked diligently to encourage hand-washing and sanitation at the House of Charity. Since November 2016, when 80 people staying at the House of Charity were sickened by norovirus, Schleigh said the protocols for public health at the house have changed.

Staff at the House of Charity monitor their clients’ gastrointestinal symptoms, and if Schleigh notices an increase in people who are sick or the severity of sickness, she immediately contacts the health district and local area hospitals to compare numbers and look at what is happening on a larger scale.

Catholic Charities Director Rob McCann said most of the homeless people who contracted hepatitis A were House of Charity patrons. The House of Charity can feed many more than it can house, however. The shelter can house 185 people overnight but feed up to 400 people a day. Some of the same protocols established after the norovirus outbreaks are being used to stop hepatitis A from spreading, McCann said.

“We’re doing what we can, but we’re also up against a pretty daunting challenge,” he said.

Since the norovirus outbreak in 2016, Schleigh said House of Charity has only had to shut down meal times once or twice, due to a certain percentage of the people in the shelter experiencing symptoms. She said two cases of norovirus last winter did not even change the House’s services because the triage and coordination was so tight.

“If we see an increase (rate of infection) that we find alarming, we increase our cleaning protocol and stop serving meals because we know that meal sites are more apt to be a place, even if we’re not the origin and it’s not our food or cooks – it is a place for it to spread,” she said.

The House of Charity does not turn people away.

“We’ll take anybody in any shape, and we don’t care if you’re dirty, and even if you won’t wash your hands, we’re still going to feed you – but we’re doing the very best that we can to work with everybody we can to not do that,” Schleigh said.

While Schleigh and her staff can encourage patrons to wash their hands inside House of Charity, she has no control over what happens outside her shelter’s walls. She said an added challenge to containing sanitation services during meal time is when people or groups show up to give food to House of Charity patrons outside the shelter, on the sidewalks or on street corners. She said sometimes patrons get sick eating this food, and there are limited ways for people to wash their hands before eating out on the street.

“I would welcome them to come volunteer if they would like to help serve meals here or prep food here or donate food to us so we can cook it and store it properly, that would be helpful,” she said.

Schleigh said she is not alarmed about the hepatitis A outbreak for now, despite the increase in cases. The health district continues to offer vaccine clinics, and free vaccines are also available at the NATIVE Project, Providence House of Charity Medical Clinic downtown as well as three Rite Aid locations, including the stores on Howard and Division streets.

“The goal is really to respond conservatively to make sure this doesn’t grow beyond the few cases that we’ve had so far. And so, by making more vaccine available and creating greater awareness across the health care community to looking for early signs of infection with vulnerable populations in particular, (it) helps us be on the front-edge instead of running behind,” said Susan Sjoberg, program manager at the health district.

Spokesman-Review reporter Chad Sokol contributed to this story.