Thirty years ago this week, the largest and most complete Tyrannosaurus Rex fossil – at the time – was found in the Black Hills of South Dakota by Sue Hendrickson. The fossil would be named for her, but that name would prove to have a second meaning as well.

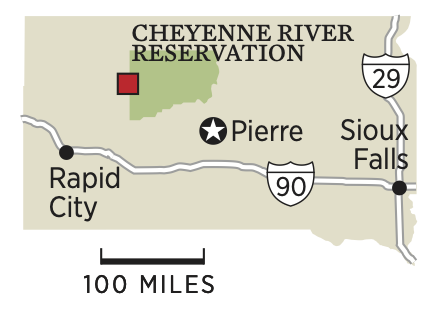

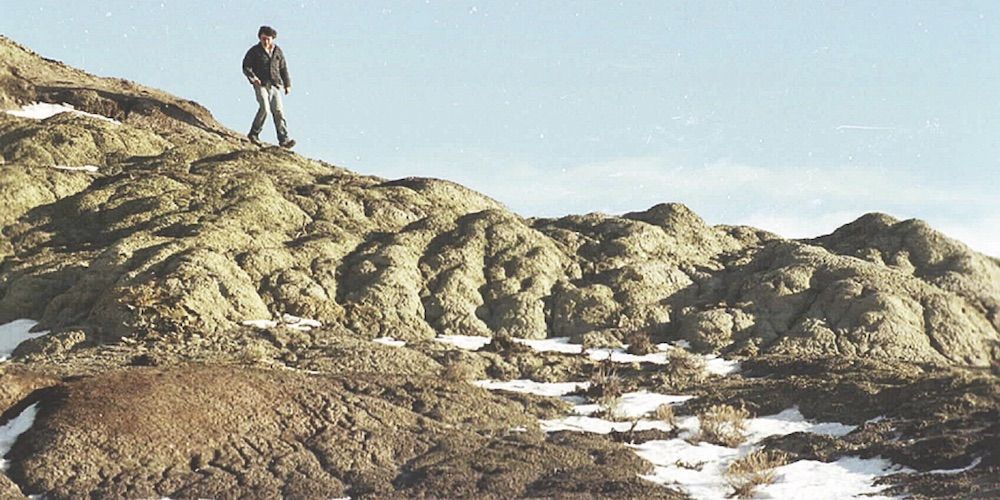

A group of fossil hunters working for the Black Hills Institute of Geological Research of Hill City, S.D., spent the summer of 1990 searching for dinosaur fossils in the Cheyenne River Indian Reservation. On what was supposed to be their last day on the site, Sue Hendrickson spent her final hours wandering through nearby cliffs when she stumbled across what appeared to be fossilized bones protruding from the side of the cliff.

The president of the Black Hills Institute, Peter Larson, recognized the bones as those from a Tyrannosaurus Rex. It took a team of workers 17 days to pull the bones from the cliff.

The find was officially labeled Specimen FMNH PR 2018, but everyone called it Sue, in honor of Hendrickson.

The fossil was notable because it was, at the time, the largest and most complete T-Rex skeleton ever found. But the rarity of such a find helped fuel a contentious custody battle that would last the better part of a decade.

The Black Hills Institute had paid the landowner, Maurice Williams, $5,000 for the right to excavate the skeleton. But as news of the find came out, Williams claimed that fee was only for the right to search for, dig out and clean fossils, not for possession of them. Williams was a member of the Sioux Tribe, so the tribe got involved in the dispute.

And then it was revealed that the U.S. Department of the Interior had been holding Williams’ property in trust for tax relief issues – which meant the feds would have had to give their consent for fossil hunting rights. Which it hadn’t.

In 1992, the FBI and the South Dakota National Guard raided the Black Hills Institute, seized the fossil and had it taken to the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology in Rapid City for safekeeping.

A federal court ruled that Sue belonged to the trust that held rights to Williams’ property. The U.S. Supreme Court upheld that ruling in 1994. The fossil was awarded to Williams and the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

In 1997, Williams auctioned off Sue. The winning bidder, Chicago’s Field Museum, paid $8.36 million for the fossil. It went on display in May 2000.

In 2014, a traveling exhibit would bring a replica of Sue to Spokane for a three-month stay at the Mobius Science Center.

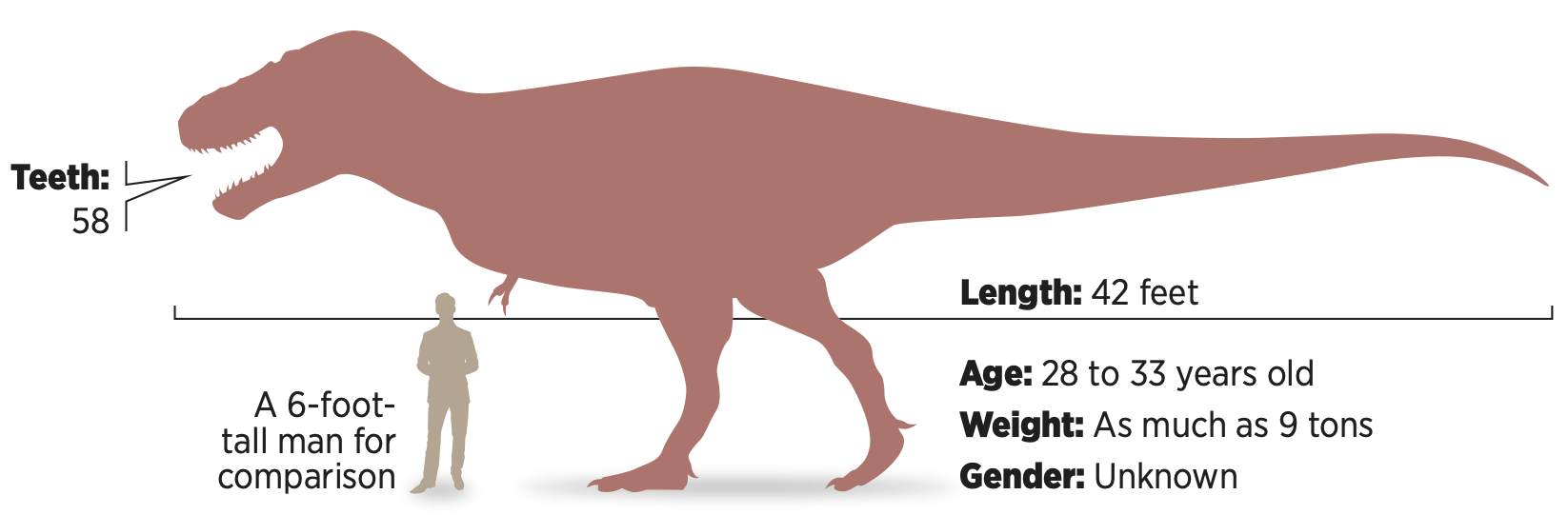

Sue by the numbers

Lived: About 65 million years ago

Our changing view of the Tyrannosaurus Rex

Originally, it was thought that the T-Rex stood upright and let its tail drag along the ground. The Smithsonian’s American Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., assembled a T-Rex skeleton it had on display upright, and that display was kept that way for 77 years, until 1992.

By the 1970s, scientists realized the T-Rex couldn't possibly have stood that way. Instead, it would have walked with its body parallel to the ground and its tail extended behind as a counterweight for its head. The first popular depiction of a T-Rex standing and walking this way: The 1993 movie “Jurassic Park.”

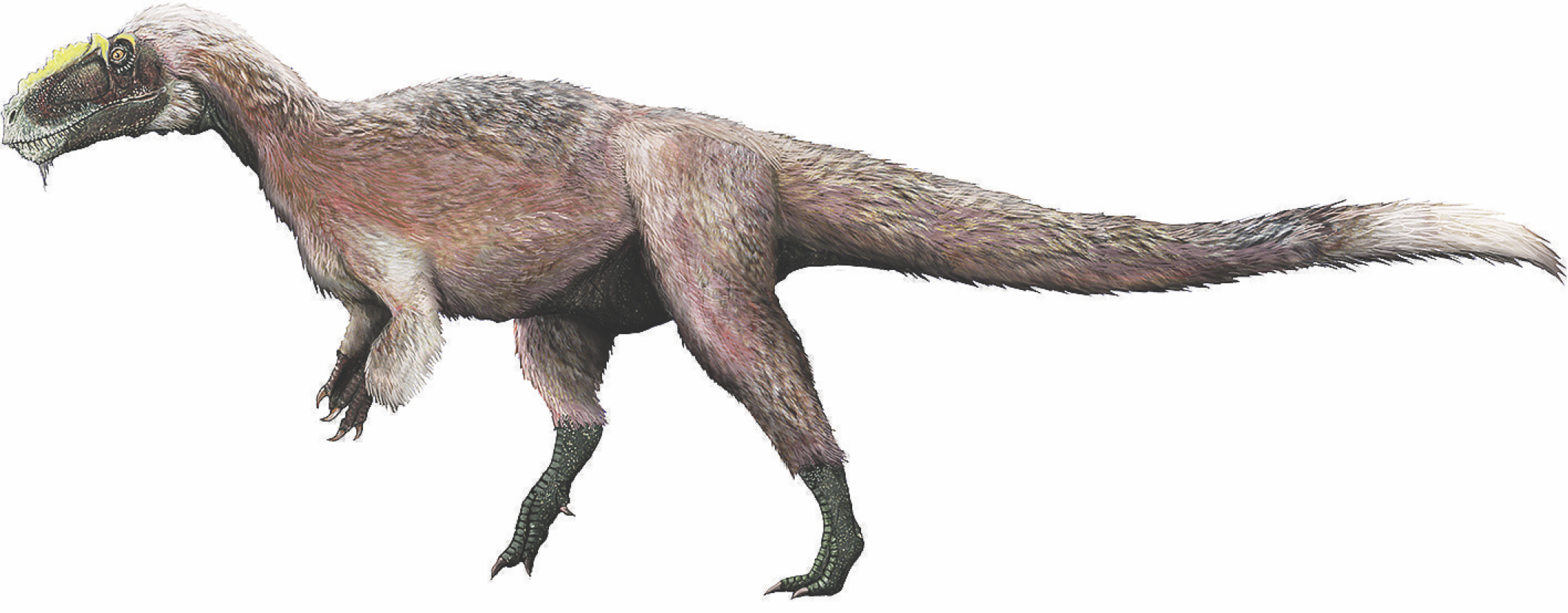

It was assumed from the very start that the T-Rex – and, in fact, most dinosaurs – were lizards and, therefore, covered in scales. By the 1990s, scientists had become convinced that many dinosaurs were actually more closely related to birds than to lizards.

Subsequent fossil discoveries have shown that the T-Rex and its closest relatives were covered with feathers. One theory is that smaller dinosaurs may have had feathers but those were replaced by scales or scale-like features as the animals grew larger.

Shown here is an artist’s rendering of an earlier species of tyrannosaur, Y. huali, discovered in 2012 in China. A study by the Beijing Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology found that Y. huali had a feathery coat.