‘There’s a bottleneck’: Interest in nursing outpaces opportunity in the Inland Northwest

The Inland Northwest doesn’t have enough nurses.

And while there are plenty of people who want to enter the profession, educators say the region doesn’t currently have the capacity to catch up.

Interest in joining the depleted nursing ranks can be seen throughout the region.

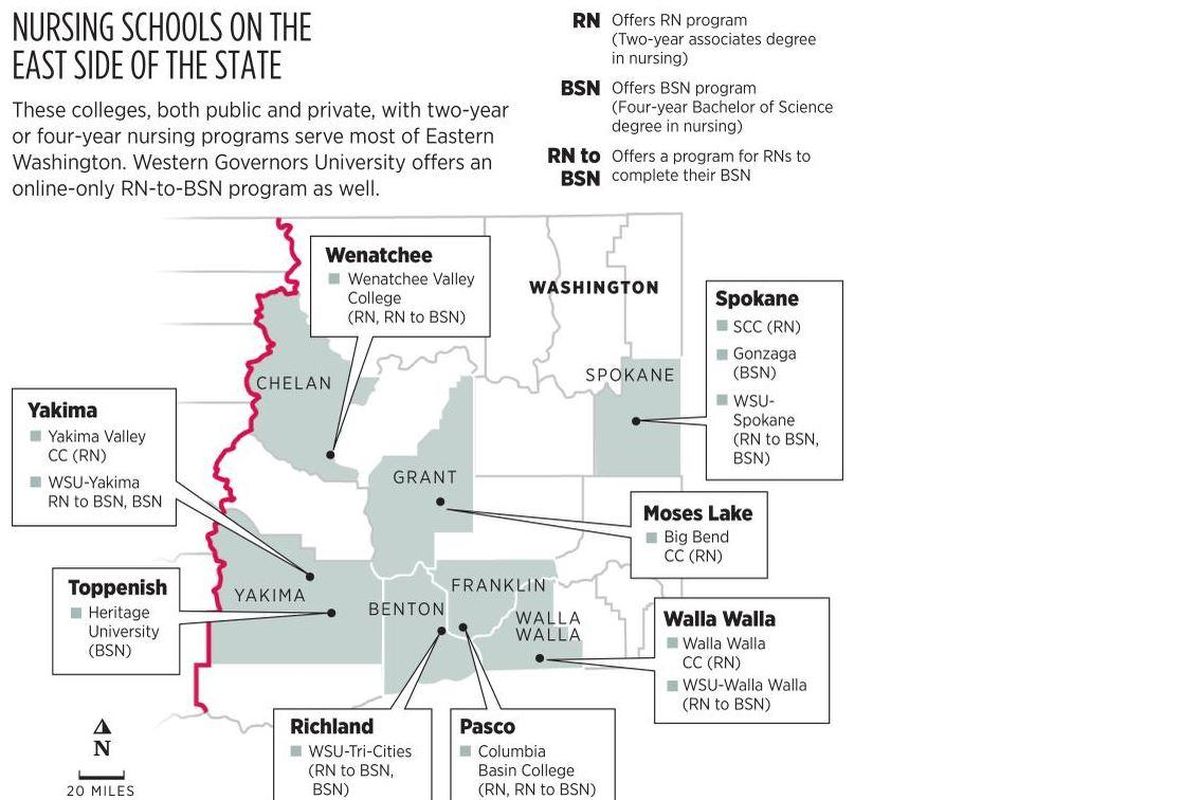

Washington State University’s three campuses with nursing programs – in Spokane, the Tri-Cities and Yakima – received nearly 1,000 applications for about 270 slots.

Spokane Community College, which offers a nursing program, accepts about 31% of applicants – or 96 students a year.

Gonzaga University had 896 applicants for 80 spots in its nursing program last year.

With interest exceeding opportunities for schooling in the area, nursing educators say the system is bogged down on both sides of the pipeline, with added pressures from the health care systems they work with to get their students hands-on experience.

Nursing shortages matter because nurses make up the largest segment of Washington’s massive health care employment sector, 2018 Bureau of Labor statistics show.

There are more registered nurses employed in the state than software developers. The nursing shortage is felt statewide, and recent labor negotiations highlight exactly how short-staffed some facilities are.

When about 8,000 nurses at Swedish hospitals in the Seattle-area announced a three-day strike at the end of January, Providence had to close two emergency departments and one labor-and-delivery unit.

Nursing programs in Spokane at WSU, SCC and Gonzaga graduate about 350 RNs each year, and students have numerous job opportunities once they graduate.

Becoming a registered nurse takes about two years of school at a community or technical college, given the right amount of math, science and other prerequisite courses. Students can also become a registered nurse through a four-year bachelor’s of science in nursing program and take the same exam as students in RN programs, called the NCLEX, to officially receive their license.

“Nurses that graduate have their pick (of jobs),” said Cheri Osler, associate dean of nursing at SCC.

Indeed, the majority of local hospitals list open positions for RNs. A survey of March 2019 SCC graduates found that 95% of students had secured jobs within three months of graduating. Some students reported getting jobs even before they graduated.

The Institute of Medicine released national recommendations about the nursing workforce a decade ago, including a goal of 80% of nurses having a bachelor of science degree in nursing by 2020. Many universities and colleges offer an RN to BSN completion program, which has coursework predominantly online for nurses who continue to work while in school.

Like SCC, many schools have capped enrollment due to the need for more nursing faculty and more clinical spots to host students during their programs.

“We have a shortage of nursing instructors, and if we don’t have enough instructors, we don’t have enough students and programs,” Osler said.

Schools have to recruit nursing educators, but they need to be able to pay nurses as much as they could be making in the field. And to teach bachelor’s level courses, a nurse must have a master’s degree in nursing.

In response to such issues, the Washington Legislature appropriated $40.8 million to raise nurse-educator salaries at community and technical colleges, including at SCC, for the next two years. Nursing groups statewide supported the measure.

“One of the really shocking things was that to be faculty in these nursing school programs, you need to have a master’s degree, yet those master’s degree-trained faculty were making less money than those new nurses they were graduating with RNs and going into the hospitals,” said Jennifer Muhm, director of public affairs at the Washington State Nurses Association. “So the discrepancy is pretty significant.”

Nursing groups say the salary increase has worked.

“We actually think that this salary increase is the best solution we’ve seen in years to be able to increase the pipeline of nurses in Washington state to help address the shortage,” Muhm said.

There are 71,386 registered nurses with Washington addresses, a 2018 survey found. But it is difficult to deduce exactly how many of them are actively practicing.

To work at solving the nursing shortage problem, as well as accurately define exactly where in the state and in what care settings there are shortages, accurate data is needed.

And that data could be coming soon. This spring, the Washington Center for Nursing will publish an analysis of national and state nurse licensing data from the University of Washington Center for Health Workforce Studies. This data will help accurately identify the demographics, education and workplace characteristics of Washington’s nurses.

The center also is working to increase the number of nursing educators statewide, hosting a workshop this year in central Washington and planning another in 2021 in Eastern Washington for nurses interested in becoming educators.

“Nurse educators and recruitment for them is a challenge,” said Sofia Aragon, executive director of the Washington Center for Nursing. “They are leaving due to benefits and pay.”

Beyond the need for more nursing educators, the need for more clinical spots limits local nursing programs from graduating more nurses.

All nursing students need clinical or practicum hours to hone their skills and put their theoretical coursework to the test in real care settings. Eastern Washington has reached its capacity in local facilities for clinical spots, local nursing educators said, and nursing programs must share limited clinical spots in Spokane-region hospitals.

“I would love to say that everybody who wants to be a nurse, come and we’ll get you prepared and send you through. But the fact of the matter is that’s not an option,” said Julie Derzay, nursing program director at Gonzaga. “We are on a desert island with limited bottles of water, and the clinical spots are our bottles of water. We try to be fair, share them, collaborate, and the number of spots we’re allowed is based on the number of students we can educate.”

Nursing educators do not want to overwhelm hospital units with students, who shadow and work with a licensed nurse for several weeks. Ensuring all students get clinical spots determines how many students are accepted into the program at Gonzaga, Derzay said.

“Essentially, we need more nurses; we would like to be able to take more,” she said. But, she noted, “there’s a bottleneck to get into those clinical spots.”

At WSU and other programs, nursing students who want to do their clinicals in other settings or at smaller hospitals can work with faculty to arrange that, but the majority of nursing students want to do clinicals and work in hospitals, local nursing program deans said.

“Most students at the BSN level are addicted to the adrenaline that comes in acute-care settings,” Derzay said.

Hospitals are also where nurses can make the most money. The median salary of a nurse in the Inland Northwest working in a hospital is $84,000. Nurses in all other work settings in this region, from long-term care to public health, make a median salary of $76,000.

Retention of nursing students is important not only to nursing programs but also to health care providers that are trying to keep recent graduates local.

Not all nursing programs have exact data on where students go when they graduate, but surveys show that the majority of recent SCC graduates stay in Eastern Washington, while the majority of WSU and Gonzaga students stay in the state, with students spread across all regions.

“A lot of our graduates will work across the whole Northwest,” said Jo Ann Dotson, BSN program director at WSU. “We’re not only trying to staff Tri-Cities, Yakima and Spokane, we see our responsibility to be state- and regionwide and if you look at the less-populated states, those areas that we still have a whole lot of nursing need and even in the large cities, there continues to be a need.”

Ideas to open up more clinical spots are out there.

Anne Hirsch, an associate dean in UW’s nursing program, found one university’s solution to clinical spots this fall in Virginia. She visited George Mason University, which has its nursing and health care program students provide free and low-cost care to their communities in university-operated clinics. This model is attractive for several reasons, Hirsch said, but mainly because it would ensure spots for students to get hands-on experience and also provide a practice space for faculty members.

“Every student – graduate and undergraduate – rotates through those clinics,” Hirsch said. “Undergraduate baccalaureate students have a caseload and patients assigned to them that they care for with chronic disease management. Advanced practice students have their own caseload and patient panel, and the faculty is there and paid by the university.”

Hirsch agreed with others that there just aren’t enough clinical sites and faculty to go around. But she also said that can change.

“We’re going to change the culture to make it part of the culture of health that we need to be educating while you’re working, so if that means a little bit fewer patients that day or a little bit of recognition given to folks who have a student with them, we need to build that into the system,” Hirsch said.

Editor’s note: On Feb. 5, 2020, this story was edited to reflect the full title of the University of Washington Center for Health Workforce Studies.