By Charles Apple

The Spokesman-Review

At 8:32 a.m. on May 18, 1980, all the rumblings, the trembling, the minor earthquakes, the bulges in the mountain and the occasional venting of steam led to an enormous eruption that generated the thermal energy equal to 26 megatons of TNT, hurled ash 15 miles into the air, killed 57 people and caused more than $1 billion in damage.

Beginning with a series of minor earthquakes that began on March 20, Mount St. Helens developed a number of bulges and gas vents, especially on its north face. This led geologists to conclude that an eruption might occur soon.

Scientific observation of Mount St. Helens would be increased over the course of the spring.

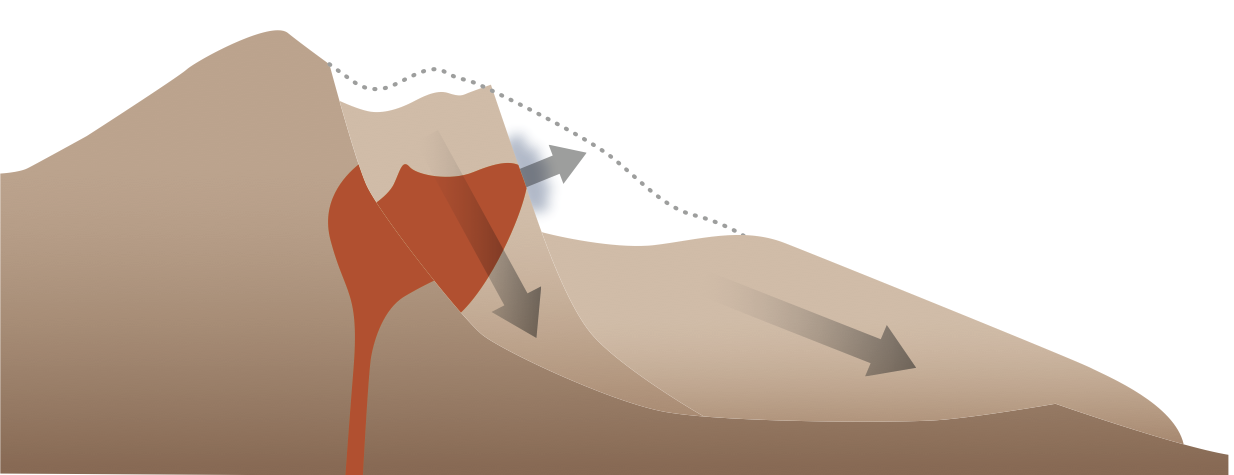

On the morning of May 18, the dome suddenly collapsed in a 5.1-magnitude earthquake. This resulted in an enormous landslide on the north side of the mountain.

Spokane residents Dorothy and Keith Stoffel happened to be flying over Mount St. Helens that morning just as it erupted.

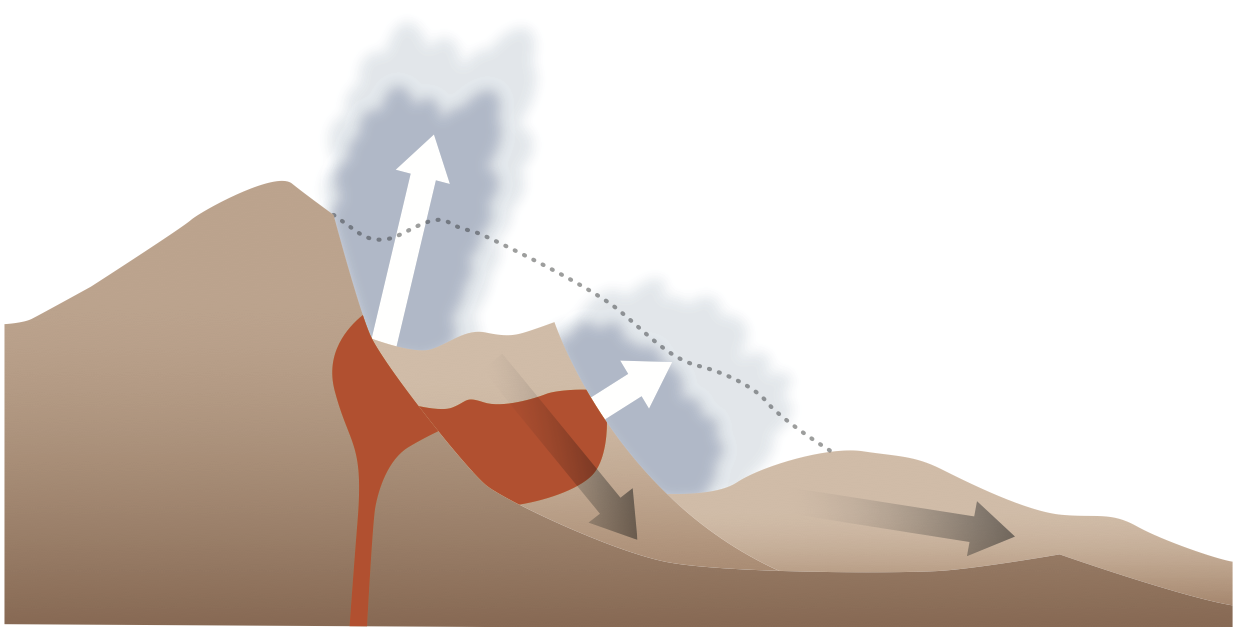

At top, a glacier falls away just as the earthquake hits, resulting in the largest landslide in recorded history.

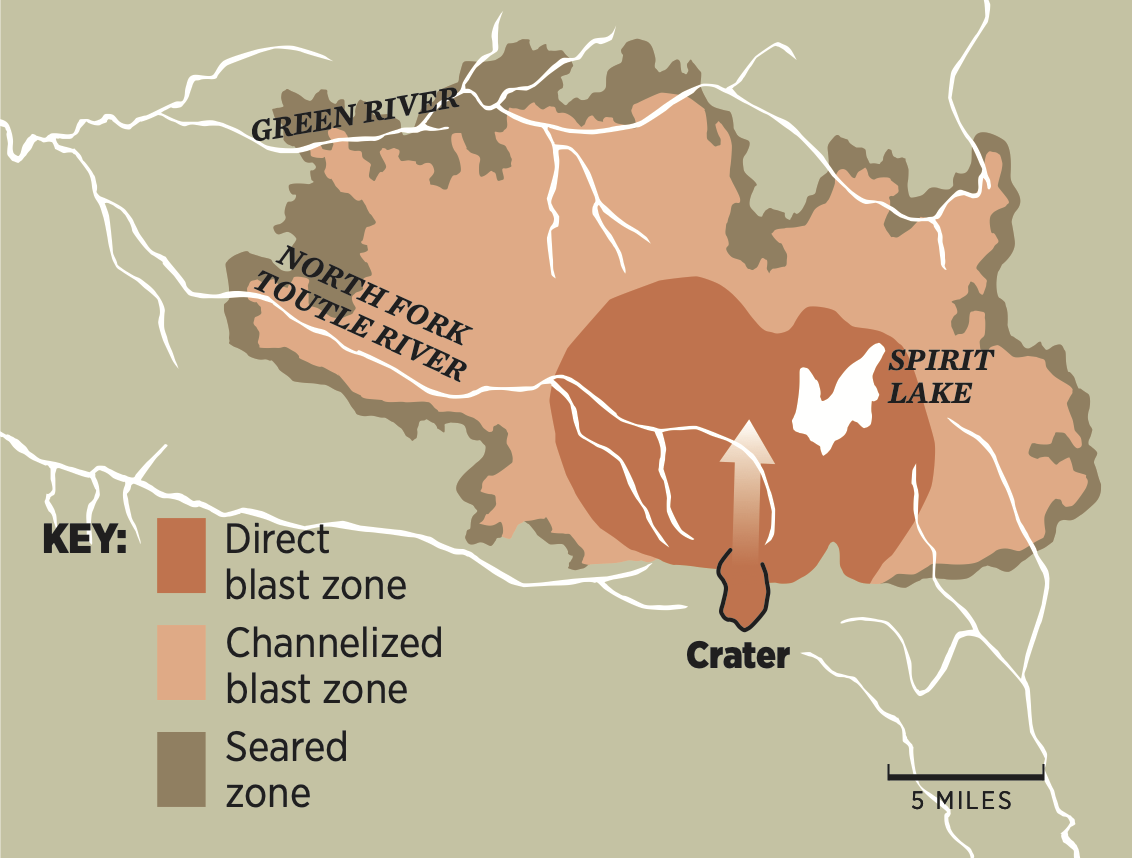

As the side of the mountain slid away, the hot gasses inside that were under intense pressure blasted northward, creating a fan-shaped path of destruction 15 to 19 miles long.

The north side of the mountain erupts with tremendous fury, ripping 1,300 feet. The Stoffels’ pilot put his plane into a nose dive to outrun the explosion and flew to Portland instead of trying to return to the airport in Yakima, from where they had set out.

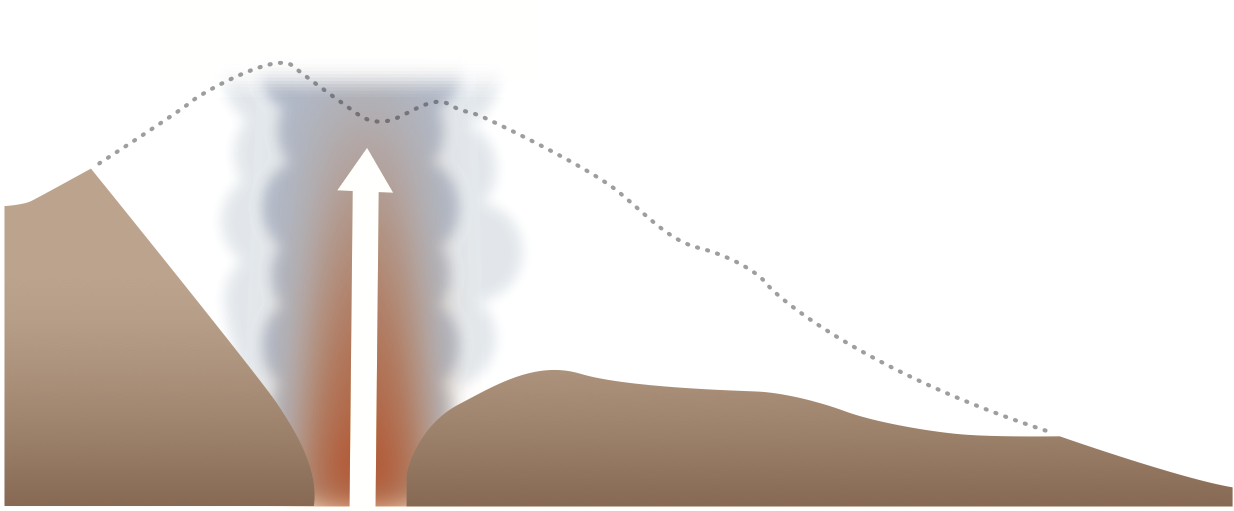

About a minute into the eruption, much of the mountain top had slid away. The upward blast – now at full strength – would continue for nine hours and would reach 15 miles into the atmosphere.

In less than 10 minutes, the column of superheated ash had risen more than 12 miles high.

Particles of swirling ash generated lightning – which in turn created forest fires. About 540 million tons of ash spewed out of Mount St. Helens that day – about the equivalent of a football field, piled 150 miles high. The photo above is one of a series that won a Pulitzer Prize for general news photography in 1981.

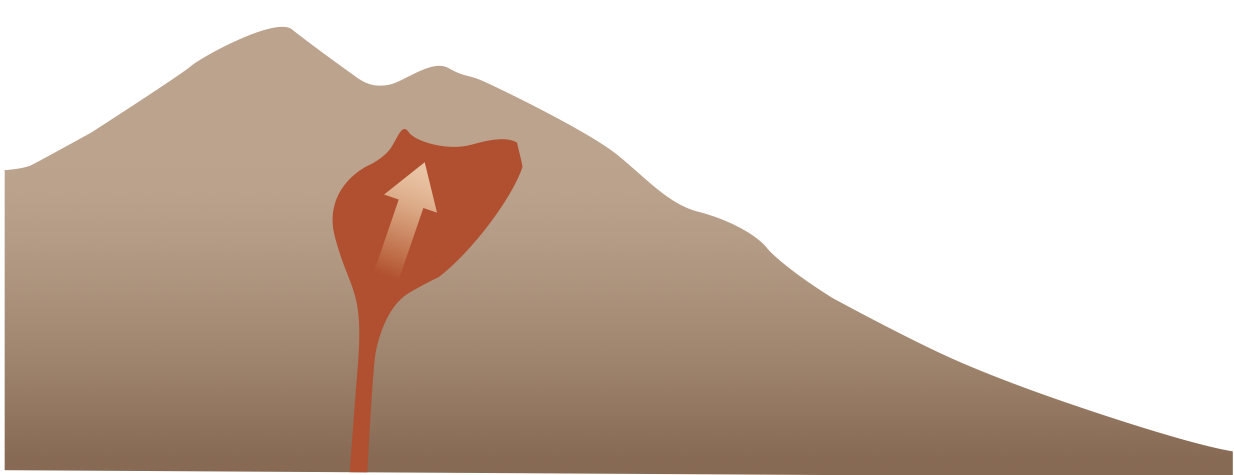

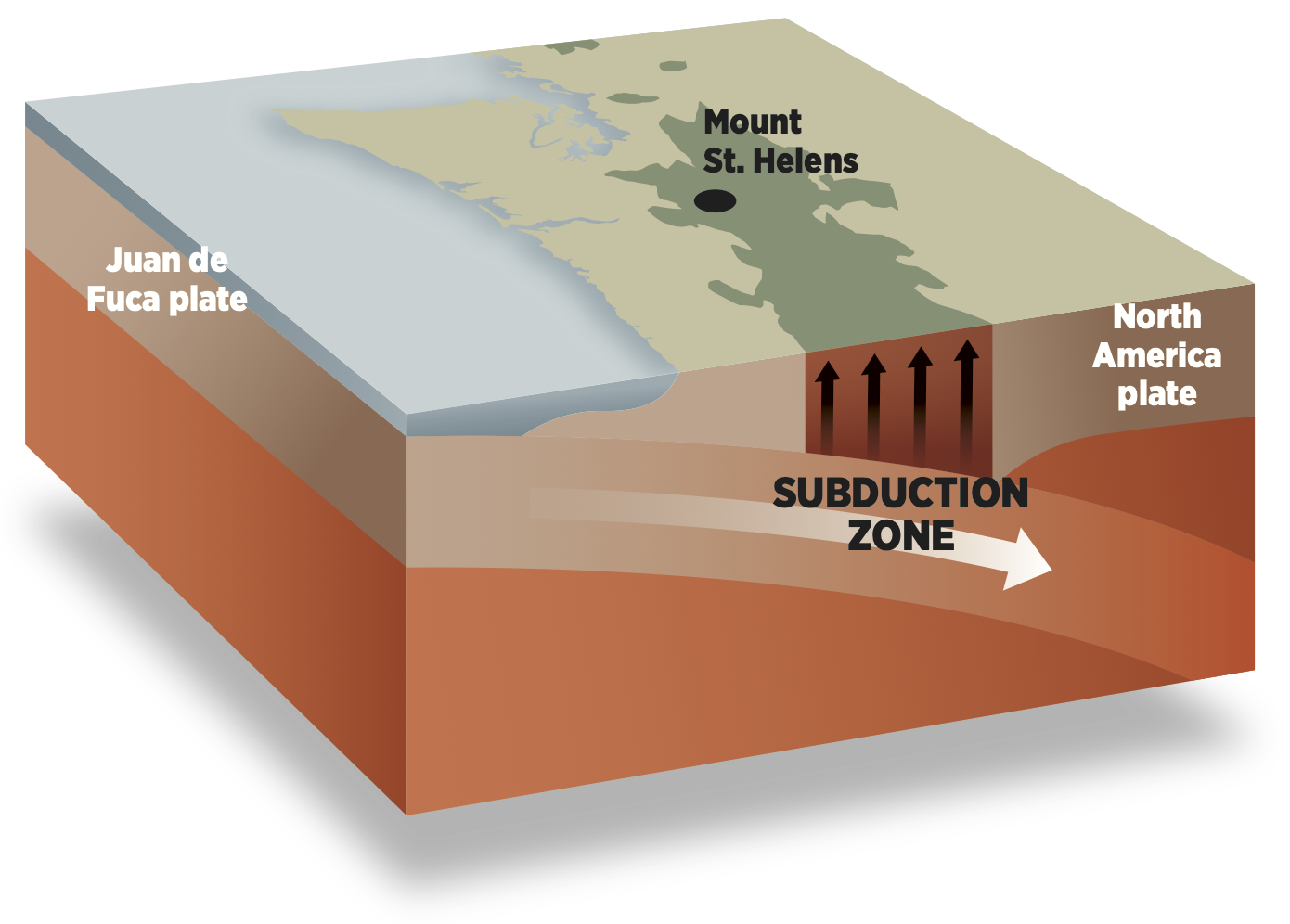

Why Mount St. Helens erupted

The Cascades mountain range – including Mount St. Helens – were formed by two sections of the Earth’s surface running into each other.

These sections, called tectonic plates, float on a sea of molten lava deep within the Earth. The Juan de Fuca plate is shoved beneath the North America plate creating high pressure and hot temperatures.

This pressure and these hot temperatures force molten rock to the surface, creating a chain of volcanoes.

Mount St. Helens had erupted several times over the centuries – most notably in 1800 – but had been relatively quiet since 1857.

A ‘stone wind’

The explosion ripped 1,300 feet off the top of Mount St. Helens and moved outward at speeds up to 200 miles per hour.

About 150 miles of forest – much of it 180-foot-tall fir trees – was cut down, uprooted or sawed in half by rocks of all sizes moving at tremendous speeds. Rock, dirt and ash forced the water out of Spirit Lake and the rivers around Mount St. Helens. The silt would clog the Columbia River, about 40 miles or so downstream, reducing navigability from 39 feet to only 13 feet deep.

The material that belched out of the mountain was a superheated 1,000 degrees. Two weeks later, some of the pumice covering the mountain still measured 780 degrees.

Airborne ash

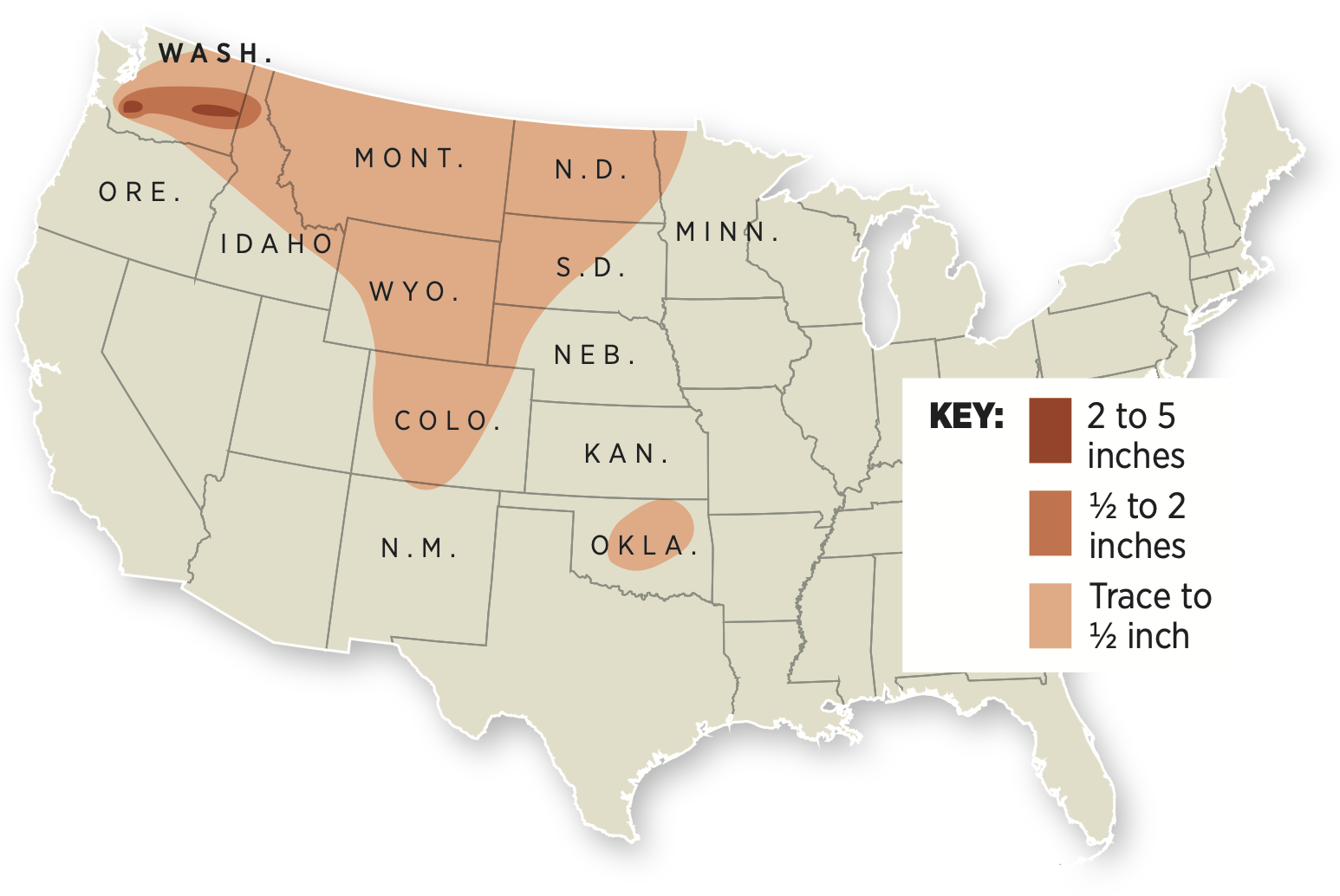

540 million tons of thick volcanic ash was thrown 15 miles into the air, where winds carried it hundreds of miles away.

The eruption continued for about nine hours. Over that time, thick layers of ash were spread across Washington and into Idaho and smaller amounts began to rain down on the Northwest and Midwest, over an area of more than 22,000 square miles.

The estimated toll for Mount St. Helens eruption:

◼ 57 dead

◼ More than 200 homes and cabins

◼ 185 miles of roads

◼ 15 miles of railroad

◼ More than 4 billion board feet of saleable timber

◼ Nearly 7,000 big game animals

◼ A total of about $1.1 billion in damage

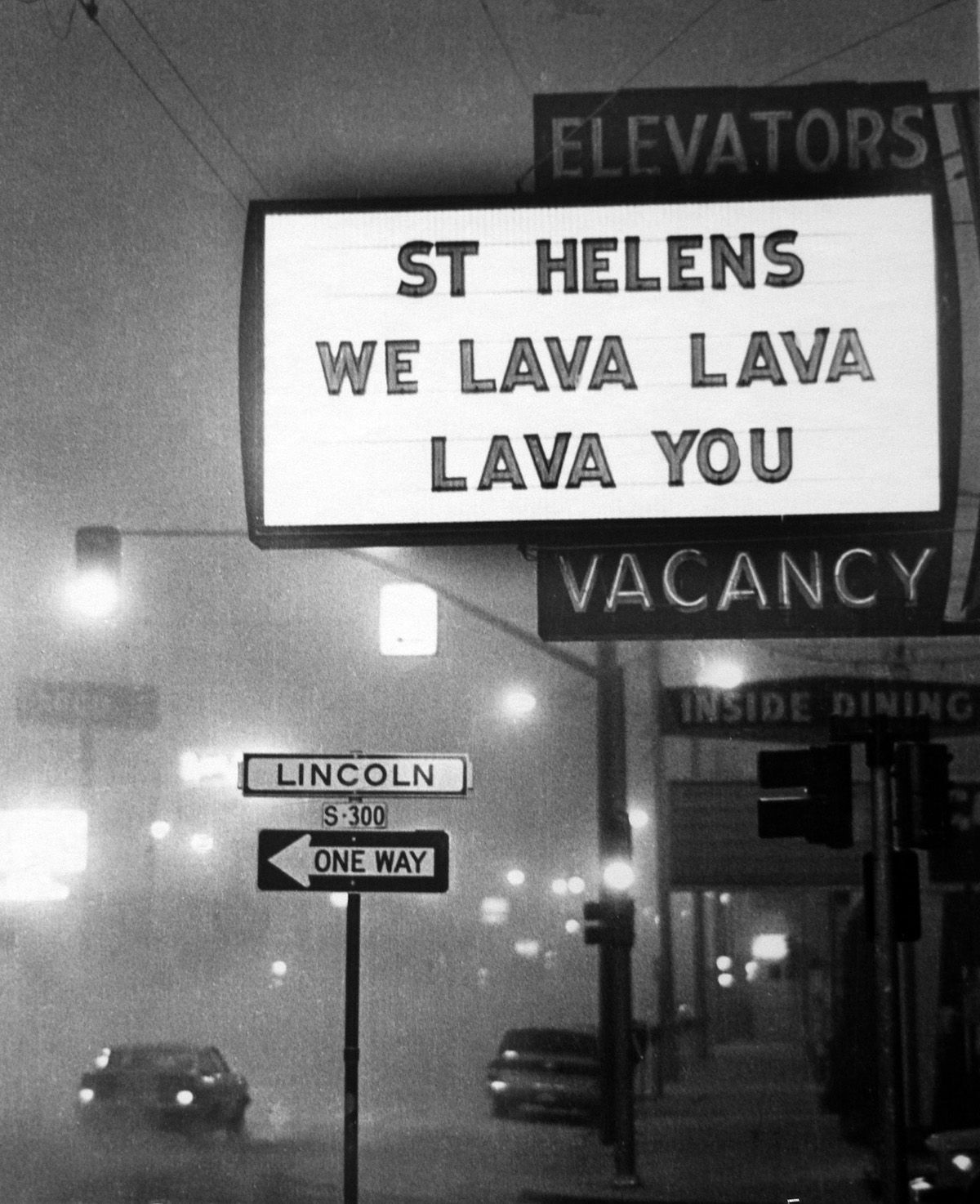

Moving at about 60 miles per hour, the cloud of ash reached Yakima by 9:45 am and Spokane by just before noon. The skies darkened. Steetlights came on and stayed on for the rest of the day.

Six inches of ash fell on Lind – quite a bit more than fell on other communities in the region. Geologists later theorized this was caused by fine particles of ash clumping inside a cloud.

Residents tried to hose the ash down the drains – until area drains became clogged. Shoveling ash proved to be difficult as well: There just wasn’t anywhere to dump it all.