Increasing property values likely will mean higher property taxes for most in Spokane County

A house sits for sale on the 1700 block of West 14th Avenue in Spokane in 2019. High demand for homes has sparked increased property values, which are causing property taxes to rise thanks to a change in state tax law benefiting schools. (DAN PELLE)

Property tax bills across the state are spiking thanks in large part to a massive overhaul of education funding approved by lawmakers more than three years ago.

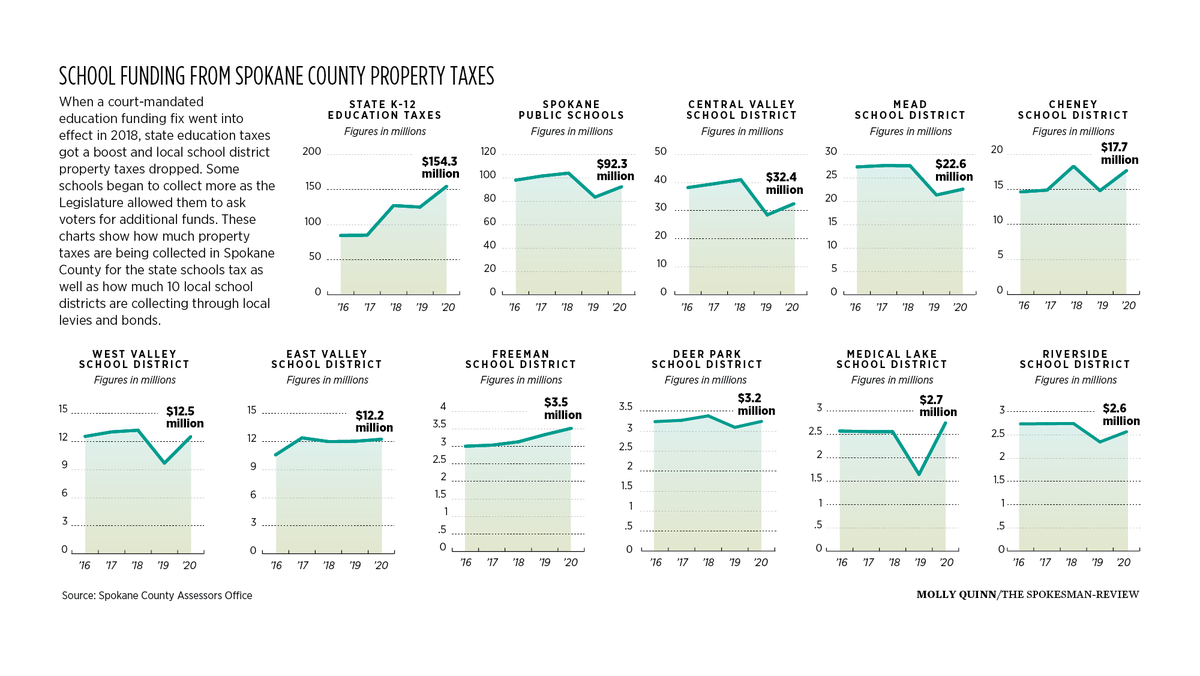

This year the county will collect $154 million in K-12 state education property taxes, a $29.4 million increase from last year. Local officials expect another increase next year, but have not yet calculated how much more the changes to tax policy will generate.

The average Spokane County resident saw their assessed property value increase by at least 9% this year, an increase that will likely be reflected on next year’s tax bill.

In past years governments and other public service providers including libraries and fire districts were only allowed by state law to increase property taxes by 1% of their total budget a year. That changed in 2018 when a court-mandated fix to fully fund public education went into effect. While most local governments are still limited to small increases in taxes, the state school property tax levy is now a fixed-rate system, which means increases and decreases are tied to property values – not a budget. In a fixed-rate system increased property values lead to higher tax collections.

About 55% of property taxes generated in Spokane County will go to education in 2020, or $361 million of $658 million. Around half of what is collected for education includes local bonds and levies voters approved for maintenance, operations and funding construction of buildings, with the remaining $154.3 million going to the state for basic education.

State Rep. Pat Sullivan, D-Covington, one of the sponsors of the bill to change education funding, said the initial proposal had included more diverse forms of funding including a capital gains tax, but architects of the bill ended up agreeing to a property tax compromise to make sure the education fix and the budget was completed before the end of that fiscal year. When the bill passed, Democrats controlled the Washington state House and Republicans controlled the Senate.

He said limiting property taxes to a 1% growth or tying them to property values both present challenges. He said sometimes schools need to grow by more than 1% in a year. While property values have grown recently, they stagnated in the years following the Great Recession. Tying taxes to property values has provided a boost in revenue, but Sullivan acknowledged it was also a risk.

“In order to be responsible and actually get things done, we had to agree to some things that we liked less, and that was one of them,” he said.

Next year will be the last year the state school portion of taxes will be calculated using a fixed-rate system. The temporary change expires in 2022, and the state’s levy rate will rise from $2.70 per $1,000 in value to $3.60, but will switch to a budget-based system.

Michael Dunn, the superintendent of North Eastern Washington’s Education Service District, said the implementation of the state’s solution to education funding has run into some issues. Dunn’s agency supports local school districts in its position below the Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction.

The solution addressed the problem of large funding gaps between school districts that had low property values and those that had high property values. He said districts with higher property values were able to spread out the cost, but in areas with lower property values, individual taxpayers had to take on a higher burden to provide needed services.

Before the Legislature approved a new funding plan, property owners in some districts in Spokane County – including Spokane Public Schools – were paying more than $4 per $1,000 in assessed value to cover basic maintenance and operations. In 2020, the district’s maintenance and operation levy has dropped to $1.60 per $1,000 in value. Most districts in the area had a rate below $2.

Dunn said the change has helped districts that have significantly lower property values, but the requirements have also created some challenges for districts that want to provide additional services because they are limited in how much in taxes they can ask voters to approve.

Mike Volz, who is the deputy county treasurer and a Republican state representative, said it’s difficult to calculate how much Spokane County residents’ tax bills will go up in 2021, because it’s dependent on their assessed value and which taxing district they live in.

He said his calculations showed, on average, most people in Spokane County would experience at least a 3% increase due to the levies.

“Because of the state school levy, in almost all cases, there will be a tax increase,” he said.

Other upticks on their 2021 property tax bill are likely tied to different levies and bonds voters approved increasing funding for fire districts, or school operational or capital expenses. Those who live in school districts that recently approved a bond or levy may see larger increases.

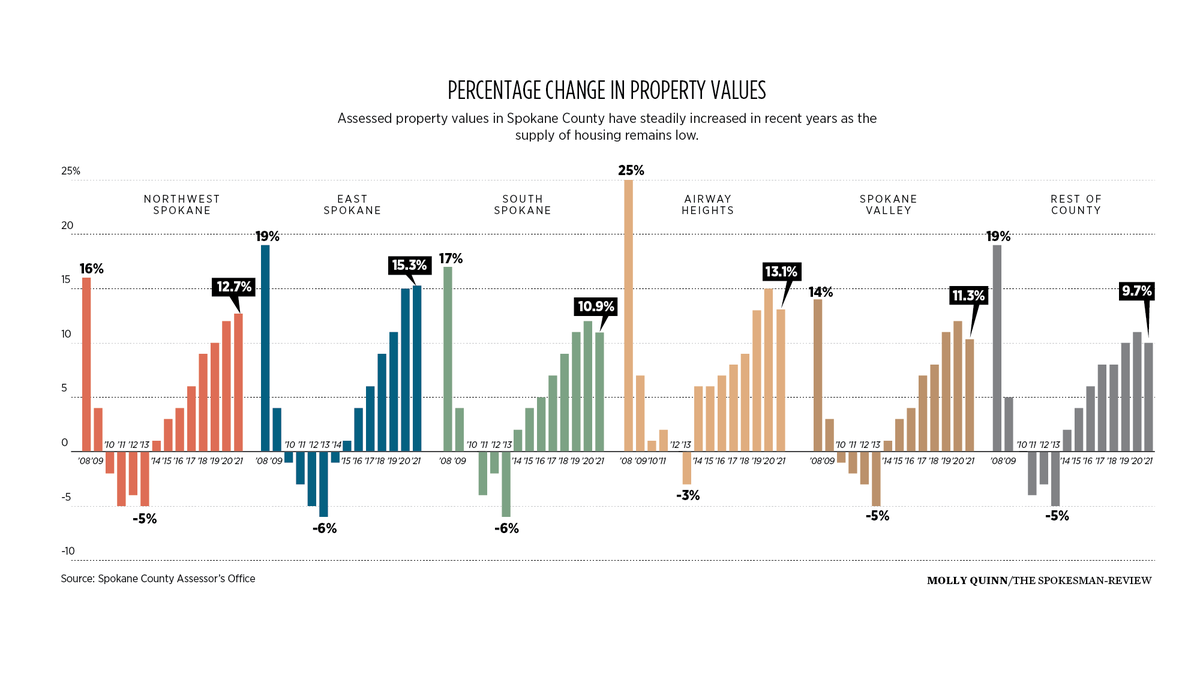

Spokane County Assessor Tom Konis said he hasn’t seen assessed property value increases this high since just before the real estate bubble burst in 2008. After 2008, property values stagnated for several years, with some properties losing value, and have steadily been increasing since 2015.

“This is a market unlike anything I’ve ever seen before,” he said.

Assessors determine property values based on the sales of property in the area. When prices go up, higher assessments usually follow.

“We go on the sale price regardless if they were in a bidding war with someone else or not,” Konis said.

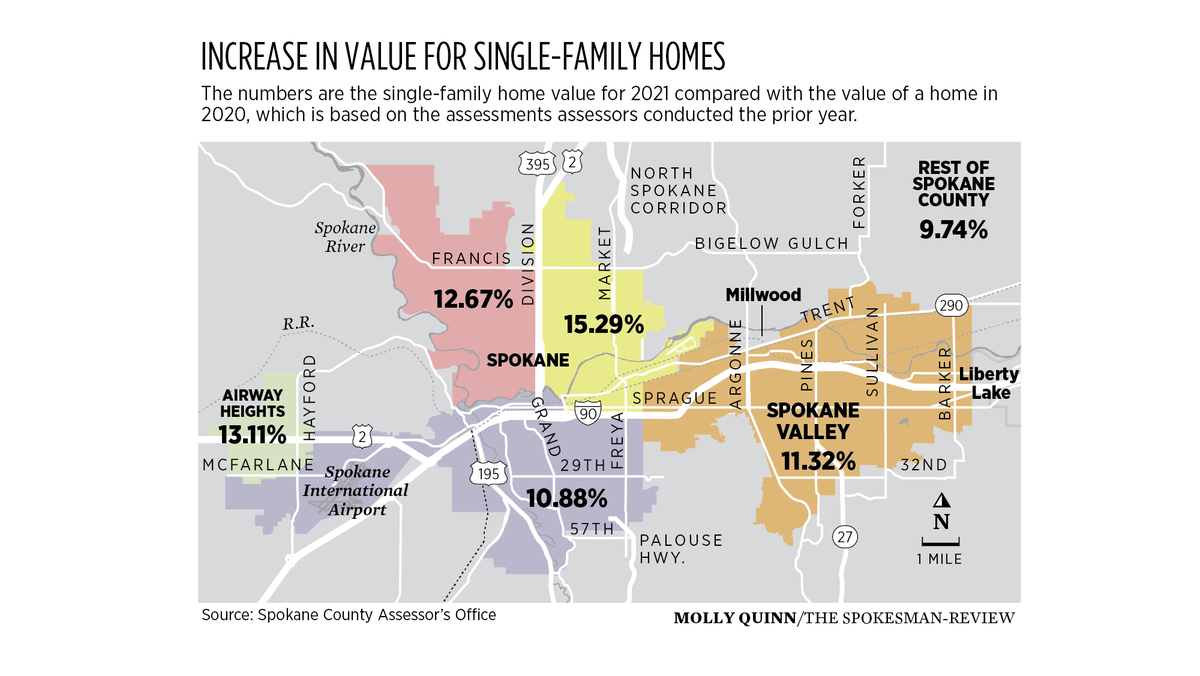

Certain areas of the county also are seeing higher assessed value increases than others, with single-family homes values in Airway Heights rising 13%, and homes in the northeast part of Spokane increasing an average of 15% in assessed values.

The factors behind rising prices and assessed values – limited supply and increasing demand – likely will get worse before they get better, said Rob Higgins, executive officer of the Spokane Association of Realtors.

“Real estate has done well, it’s still really strong, but our big Achilles’ heel is lack of inventory,” Higgins said.

He said lack of available properties has been an issue in Spokane County for years, with some areas of the county experiencing a more acute shortage than others.

He added COVID-19 exacerbated the shortage of housing, with some homeowners who would have considered selling deciding to wait.

Higgins noted some may have been nervous about the prospect of showing their home to strangers during a pandemic, or feared they wouldn’t be able to buy another home and safely move.

The number of people looking to buy has not decreased, Higgins said, with many people looking to take advantage of low interest rates and offering far more than the list price to outbid other buyers. He said some who were working from home, in apartments in Spokane or other cities may be looking to buy a house in Spokane County as they look for solutions to working from home in the long-term.

Konis said some of the biggest increases in property values were for parcels valued between $175,000 and $200,000, which he and Higgins agree is the most active market.

“It’s the lower ranges that are seeing the biggest increases, and that’s because people really want to get into housing,” Higgins said.