Difference Makers: Taking after namesake, WSU’s Steve Gleason Institute reaches new heights in battle against ALS

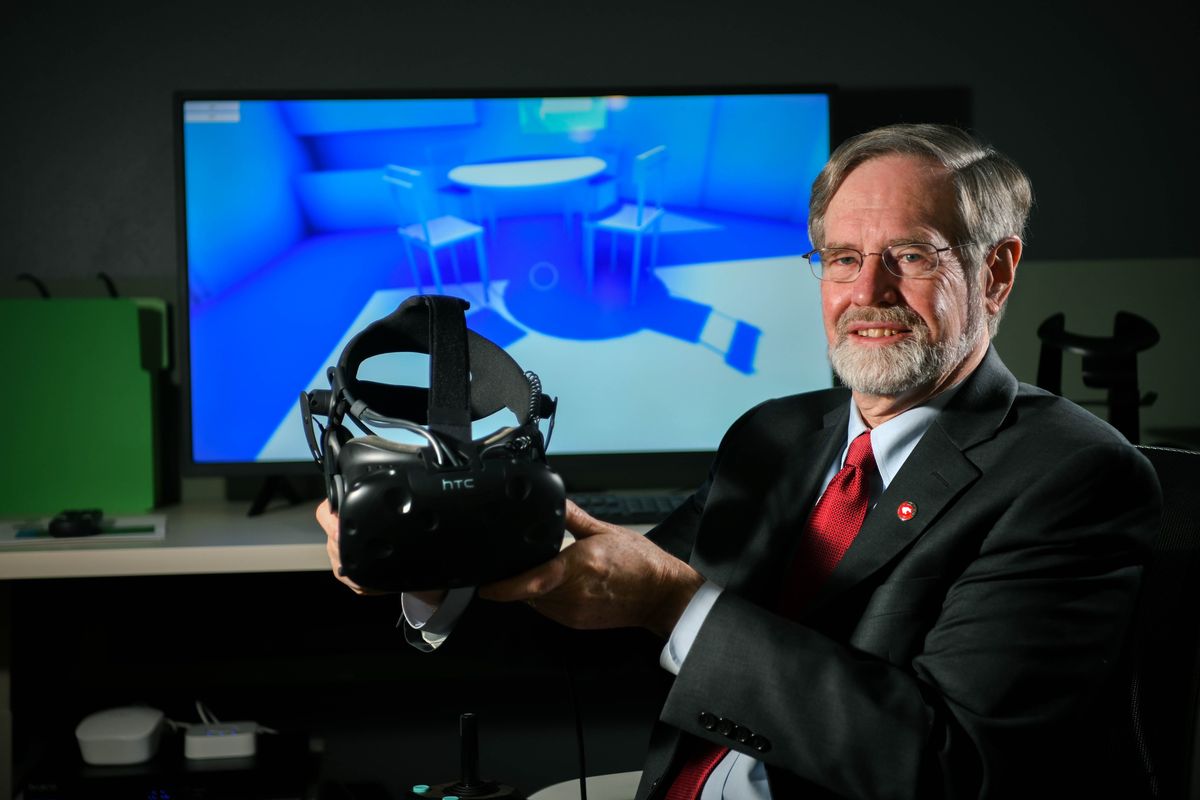

Dr. Ken Isaacs is director of the Steve Gleason Institute for Neuroscience in Spokane. Here he demonstrates a WSU Virtual Wheelchair Training Simulator that helps teach patients to use a motorized chair. (DAN PELLE/THE SPOKESMAN-REVIEW)Buy a print of this photo

Steve Gleason says he feels the best he has felt in several years.

Coming up on 11 years since he was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, the 44-year-old Spokane native said it’s been a while since he has been in the hospital for any illness or sickness. ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig’s Disease, is a progressive nervous system disease that degrades and destroys nerve cells in the spinal cord and brain, eventually causing loss of muscle control.

Gleason has fully progressed with ALS – “I don’t really have anything left to lose physically,” he explained via email – which he said allows him to focus on living and being productive.

Gleason has since made it his mission to help individuals suffering from neurodegenerative diseases live their best lives.

He and his wife Michel founded Team Gleason, a nonprofit organization that’s raised millions of dollars toward the advancement of supportive technology, including home automation devices, wheelchairs navigated with sight and voice banking equipment.

One of the projects benefiting from Team Gleason’s efforts came online this past year.

WSU’s Steve Gleason Institute for Neuroscience opened its new Adaptive Technology Center in October, serving as a testing ground for patients with neurodegenerative diseases and related disorders to see what kind of technology might serve to enhance their lives.

“Spokane is at a point of, in my view, evolving into a very substantial, regional, national center,” said Dr. Ken Isaacs, who was named director of the Steve Gleason Institute in October.

Founded in 2019, the institute takes a three-pronged approach with clinical research, discovery research and adaptive technology to providing services for patients suffering neurodegenerative diseases.

Beyond his role at the Steve Gleason Institute, Isaacs has served as the regional director for neuroscience at the Providence Neuroscience Institute in Spokane since 2015. The Providence institute’s ALS clinic collaborates with the Steve Gleason Institute.

Coming into his role at the Steve Gleason Institute with more than 30 years of experience in neurology, Isaacs previously served as president of the Washington State Medical Association and is also a former chair of the Washington Health Foundation.

Isaacs said the Adaptive Technology Center is also a doorway for innovation in furthering the available technology.

He offered a scenario: If a visitor was to explain a challenge they face in their lives, such as a certain technological need, innovators with WSU’s Biomedical Engineering and Design Service Center and Center for Innovation could theoretically take a look at somehow making a solution into an available reality.

“I think the Gleason Institute of Neuroscience has a real opportunity to grow into the future on a generational timescale to provide not only Spokane with a foundational presence in degenerative neuroscience research and care, but actually a much broader presence in even the broader region in the western United States,” Isaacs said.

The Adaptive Technology Center is still open by appointment only, said Theresa Whitlock-Wild, the center’s project manager.

To date, the center has provided tours for a couple of dozen families and local neurologists, she said, while the facility is also planning to host representatives from the local and Seattle VA hospitals.

Whitlock-Wild was largely responsible for the facility’s design. It was “a labor of love” for her, she said, as her husband, Matthew, suffers from ALS.

The facility is modeled with an office room used for virtual reality wheelchair simulations, a bathroom outfitted with adaptive equipment and a kitchen that uses smart home appliances. The Gleason institute hopes to build out the Adaptive Technology Center for more testing space in the rear of the building.

“When I designed the Adaptive Technology Center,” she said, “I wanted it to be as inclusive for families as well as scientists, researchers, therapists, doctors and really hoping to challenge the way that we provide care for these families, find ways to find immediate solutions for their needs and alleviate the burden of them doing that research themselves.”

Whitlock-Wild said she and her husband have met Gleason a few times in the past through Gleason Fest, a local music festival that benefits the Gleason Initiative Foundation.

“Steve has done a really good job of showing people, ‘This is the hand I was dealt and I’m going to live this hand all the way through’ … That is inspiring. That is what gives people hope,” she said. “What I’m trying to do is take the families that maybe aren’t as well known as Steve, the ones that are fighting it by themselves that don’t have the resources Steve has, and say, ‘You’re just as inspirational and you’re just as worthy as being noticed and we need to help you maintain your quality of life as well.’ ”

Gleason said he continues to have moments of severe emotional pain and struggle.

“I have very challenging moments each day, but I’m lucky to tell you that I also have moments of unexplainable joy and peace each day as well. And, at the end of each day, before closing my eyes for the night, I feel enormous exhaustion, but also, equally enormous gratitude for this life I’m living.”

Four years before his diagnosis, Gleason – a Gonzaga Prep graduate and a Washington State University football standout who played professionally for the New Orleans Saints – was better known for his blocked punt against the Atlanta Falcons on Sept. 25, 2006, that led to a touchdown. The touchdown was the Saints’ first in New Orleans three years after Hurricane Katrina.

The Saints erected a statue outside of the Superdome immortalizing the block by Gleason, who was given the news that he had ALS on Jan. 5, 2011. Doctors at the time estimated Gleason had as many as five years to live.

Isaacs has one of Gleason’s sayings posted on his wall: “I believe my future is greater than my past.”

“His inspiration has been something that, I think, serves all people,” Isaacs said, “because if we imagine ourselves confronted with a disorder as relentless and progressive as ALS, and to do so with a spirit of, ‘I can do more,’ that’s an inspiration that we can all take.”

As a partner with the Steve Gleason Institute, Team Gleason contributed several donations to help launch the Adaptive Technology Center, including eye tracking devices, Microsoft Surface Pros, iPads and a power wheelchair worth more than $40,000.

A unique contribution with the chair is the Ability Drive system, a module developed out of a Microsoft hackathon that allows users to navigate the wheelchair with their eyes, said Gleason, an Ability Drive user himself. He said Team Gleason is working to help change the reality that individuals with neurodegenerative diseases continue to face: overpriced machines powerful enough only “for someone to be a fraction of a human.”

To that end, Gleason said he is interested in the future in exploring ideas including augmented and virtual reality technology, exoskeletons and brain-computer interfaces.

“I believe we have the power to help someone like me, who can’t move, use technology to be far more independent and to communicate in real-time,” he said. “What ALS and other diseases or injuries take away, technology can give back.”