‘There’s a lack of trust’: Native American education in Spokane Public Schools

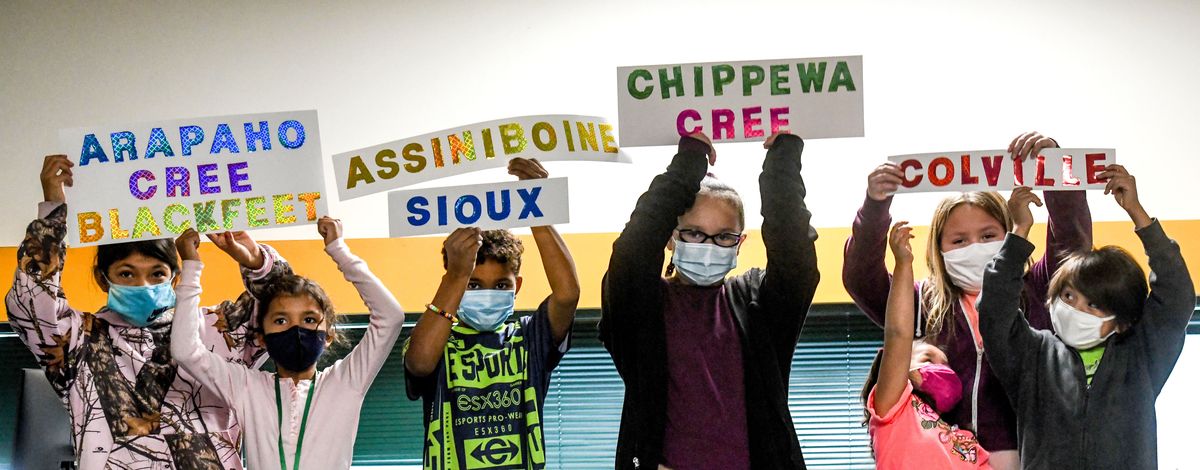

During a recent class at Grant Elementary School, several Native American students held up identifying signs that reinforced a point that the general population has seldom understood.

Not one of the signs read “Native American.” Instead, they identified the children as members of the Spokane, Colville, Assiniboine and other tribes.

For Tamika LaMere, the director of the Native Education program at Spokane Public Schools, this was a teachable moment for the students and their guests.

“That’s one of the goals of our program, that we are educating internally and externally, and not perpetuating stereotypes,” LeMere said.

“We talk about equity and diversity that lies in our people as distinct tribal nations: our language, our style of dress, the food we eat – all the things that make us feel distinct – so that we don’t perpetuate those stereotypes.”

Of the 547 federally recognized tribes, 130 are represented by almost 2,000 students in Spokane Public Schools.

Based on the statistics collected by the state superintendent of public instruction, Native American Students need help – in the classroom and out. To that end, LaMere and her assistants focus on the latter – providing cultural enrichment through traditional activities such as drumming, singing and cooking.

Raised in Great Falls, Montana, LaMere is a member of the Little Shell Chippewas, which, like so many tribes, no longer has land to call its own.

While it’s important to acknowledge that the school district and the city sit on the unceded lands of the Spokane Tribe, she also understands the needs of urban-dwelling Native Americans “with no knowledge of who they are as Native people.”

“Some kids, you ask them what tribe they belong to, and they won’t know,” LaMere said.

At the same time, Native American students in Spokane and elsewhere struggle inside and outside of the classroom.

In the spring 2020, about 78% of the district’s Native American and Alaska Natives graduated on time compared to 89% of the overall population.

In that same year 59% of Native American ninth-graders passed all their classes, compared to 74% for all students. One out of eight dropped out before their senior year.

Those numbers are better than national averages and comparable to those in other districts around the state – with one glaring exception: Spokane has one of the lowest kindergarten-readiness rates in the state at 32%; yet for Native American children, it’s only 18%.

Some of those same children have grandparents who were forced into boarding schools that attempted to strip away their cultural identities.

“There’s a lack of trust,” said LaMere, a former counselor at Glover Middle School who has led the Native Education program since the summer of 2020.

That’s the challenge: to build trust among Native American families that the educational system will help them assimilate the knowledge and experiences that will help them succeed while not being assimilated themselves.

Focusing on areas of greatest need, the Native Education staff works primarily at five elementary schools: Stevens, Grant, Logan, Regal and Bemiss.

The work includes intervention with students who are struggling behaviorally and socially – “to keep them engaged, to have someone they can go to,” LaMere said.

That task was complicated by the COVID-19 pandemic, as many families retreated to their homes; LaMere and her staff responded with in-home visits.

While serving as a liaison with teachers and staff, the program also attempts to provide consistent support to Native American students.

In line with the signs held by LaMere’s students, other students are getting an education.

In March 2018, the Legislature passed Senate Bill 5028, which requires teacher preparation programs to integrate the “Since Time Immemorial” tribal sovereignty curriculum into existing Pacific Northwest history and government requirements.

For non-Native students, the curriculum changes are intended to create greater awareness and compassion. For native students, it can teach strength and resiliency, foster positive identity development and help uphold tribal sovereignty.

“To help them feel visible,” LaMere said.