Telescopes team up to forecast an alien storm on Titan

It was a cloudy day on Titan.

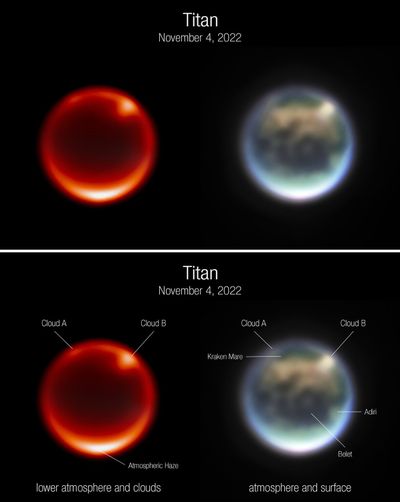

That was clear on the morning of Nov. 5 when Sébastien Rodriguez, an astronomer at the Université Paris Cité, downloaded the first images of Saturn’s biggest moon taken by NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope. He saw what looked like a large cloud near Kraken Mare, a 1,000-foot-deep sea in Titan’s north polar region.

“What a wake-up this morning,” he said in an email to his team. “I think we’re seeing a cloud!”

It triggered a kind of weather emergency among the Al Rokers of the cosmos, sending them scrambling for more coverage.

Titan has long been a jewel of astronomers’ curiosities. Almost the size of Earth, it has its own atmosphere that is thick with methane and nitrogen – and even denser than the air we breathe. When it rains on Titan, it rains gasoline; when it snows, the drifts are black as coffee grounds. Its lakes and streams are full of liquid methane and ethane. Beneath its frozen sludgelike crust lurks an ocean of water and ammonia.

Would-be astrobiologists have long wondered if the chemistry that prevailed during the early years of the Earth is being re-created in the slushy mounds of Titan. The potential precursors of life make the smoggy world (where the surface temperature is minus 290 degrees Fahrenheit) a long-shot hope for the discovery of alien chemistry.

To that end, missions are being planned to Titan, including sending a nuclear-powered drone named Dragonfly to hop around the moon of Saturn by 2034 as well as more notional voyages like sending a submarine to explore its oceans.

In the meantime, however, despite observations by Voyager 1 in 1980 and the Cassini Saturn orbiter and its Huygens lander in 2004-05, planetary scientists’ models of Titan’s atmospheric dynamics were still only tentative. But the Webb telescope, which launched almost a year ago, has infrared eyes that can see through Titan’s haze.

So when Conor Nixon of the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center got Rodriquez’s email, he was excited.

“We had waited for years to use Webb’s infrared vision to study Titan’s atmosphere,” Nixon said. “Titan’s atmosphere is incredibly interesting, not only due to its methane clouds and storms but also because of what it can tell us about Titan’s past and future, including whether it always had an atmosphere.”

Nixon reached out that same day to two astronomers – Imke de Pater at the University of California, Berkeley, and Katherine de Kleer at the California Institute of Technology – who were affiliated with the twin 10-meter Keck Telescopes on Mauna Kea in Hawaii and have called themselves the Keck Titan team. He requested immediate follow-up observations to see if the clouds were changing and which way the winds were blowing.

As de Pater explained, such last-minute requests are not always possible, as telescope time is a precious commodity.

“We were extremely lucky,” she said.

The observer on duty that night, Carl Schmidt of Boston University, was a collaborator of theirs on other planetary studies.

The Keck staff, de Pater added, is also eager to support Webb telescope observations.

“They love the solar system objects,” she said, “since they are just neat, and always changing over time.”

With the visible light images from Keck and infrared pictures from the Webb telescope, Nixon and his colleagues were able to probe Titan from features on the ground through the different layers of its atmosphere – everything that a long-range weather forecaster might need.

And more is on the way.

In an email, Nixon said his team was particularly excited to see what would happen in 2025, when Titan would reach its northern autumnal equinox.

“Shortly after the last equinox, we saw a giant storm on Titan, so we’re excited to see if the same thing happens again,” he said.