We the People: Senate rules for filibuster up for debate. Here’s where Washington’s senators stand

Each week, The Spokesman-Review examines one question from the Naturalization Test immigrants must pass to become United States citizens.

Today’s question: How many senators does each state have?

The Constitution lays out a vision for two bodies to serve in the legislative branch: the House of Representatives and the Senate.

The House would be a larger, more diverse body while the Senate would be a smaller body that could partake in deliberation and meaningful debate on a variety of topics.

While the number of representatives varies by state, the number of senators is the same: two each. Washington’s are Democrats Maria Cantwell, who’s served since 2001, and Patty Murray, who’s served since 1992 and is currently up for re-election.

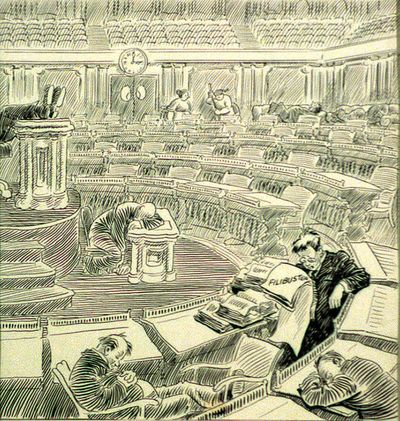

One element of the Senate rules, which some say helps with meaningful debate while others say hurts it, is the filibuster. And senators, including Washington’s own, have talked for years of reforming it.

Most recently, Democrats have pushed for reforms or exceptions to the filibuster to pass voting rights legislation and legislation to expand abortion access.

The filibuster is the ability for senators to prolong debate and delay or prevent a vote on a bill. The only way to end the debate is with 60 votes, which can be difficult to do with such a divided Senate, currently 50-50.

The Senate is supposed to “deliberately debate the legislation, so it’d be good for the country,” Gonzaga law professor Upendra Acharya said. And the filibuster is said to allow that to happen.

But with such a divided body, it can be difficult to get anything passed because the minority can use the filibuster to essentially kill a bill before it’s even put up for a vote, Acharya said.

“In the present days, the filibuster has not been used to deliberate,” he said. “It has been used to block legislation.”

The Constitution requires 51% of senators to pass a bill, so some people have argued the 60-vote requirement to end debate is unconstitutional, he said.

“It informally changed the constitutional requirements to pass a bill as opposed to what the text of the Constitution requires,” Acharya said.

Calls to reform the filibuster or allow exceptions for certain legislation are not new, but have received renewed support in recent years as Democrats have tried and failed to pass voting rights legislation and legislation to codify Roe v. Wade, which was overturned by the Supreme Court earlier this year.

Both Cantwell and Murray have been outspoken about their support of creating exemptions to the filibuster to codify Roe v. Wade.

In last week’s debate, Murray held her position for creating exemptions to the filibuster to codify Roe v. Wade. She said she believes the rules of the Senate should change to uphold constitutional rights, such as the right for a woman to choose and voting rights.

Cantwell said earlier the same day that she would eliminate the filibuster for the measure.

It’s not the first time either of them have pushed for changes in the filibuster process.

Murray became a strong proponent of changing the filibuster after the Senate failed to pass voting rights legislation.

In an interview with KUOW earlier this year, Murray said she believes in the right of the minority but that the way the Senate is being run right now “is keeping us from protecting our democracy.”

She acknowledged that if Republicans took control of the chamber, they could use the change to pass bills without debate.

“I also think that the way this filibuster rule has been implemented is now pushing Democrats and Republicans further into their own corners, rather than toward collaboration, which is really what the filibuster was designed to do, to force people to work together,” she said at the time.

But Murray has also defended the use of the filibuster by her party at times. In 2003, Democrats filibustered two federal judicial nominees, Priscilla Owen and Miguel Estrada. During Owen’s nomination Murray said in a statement that the filibuster was not “new or unique.”

“Every senator is familiar with the filibuster process,” Murray said. “It is one of the many tools available to every Senator.”

She went on to say the filibuster is not a step the Senate should take often, or lightly, but that it was “clearly warranted” in this case.

Last year, Cantwell tweeted that she did not want the Senate procedure to stand in the way of important issues like voting rights.

She also pointed to her continued support for a proposal from Sen. Jeff Merkley, D-Oregon, that would create a “talking” filibuster.

Merkley’s 2011 proposal would require at least 41 senators to vote for additional debate.

It would require senators to talk at length on the Senate floor for a debate to continue.

For example, under Merkley’s 2011 plan, if the Senate held a vote to end debate and a majority voted to end the debate but not 60 – the current requirement to end debate – the Senate would have “extended debate.” During extended debate, one senator must be on the floor speaking at all times. If there is no senator present to speak during the debate, another vote would be had to end the debate but that vote would only need a simple majority of 51 senators to pass.

In her 2021 tweet, Cantwell said she supported the bill at the time and she still does.

Merkley’s proposal received a vote in 2011 but did not pass. Both Cantwell and Murray voted for it at the time.

Any new reforms to the process wouldn’t be the first time the filibuster has been changed.

Prior to 1917, there was no rule to end debate and force a vote, but the Senate voted in 1917 to require a two-third majority to end the debate. That number changed again in 1975 when the Senate changed their rules to allow three-fifths, or 60 senators, to end debate.

In 2013, Democrats voted to remove the filibuster for presidential nominees. Republicans voted to do the same for judicial appointments in 2017.