With a shutdown in view, McCarthy plays a weak hand

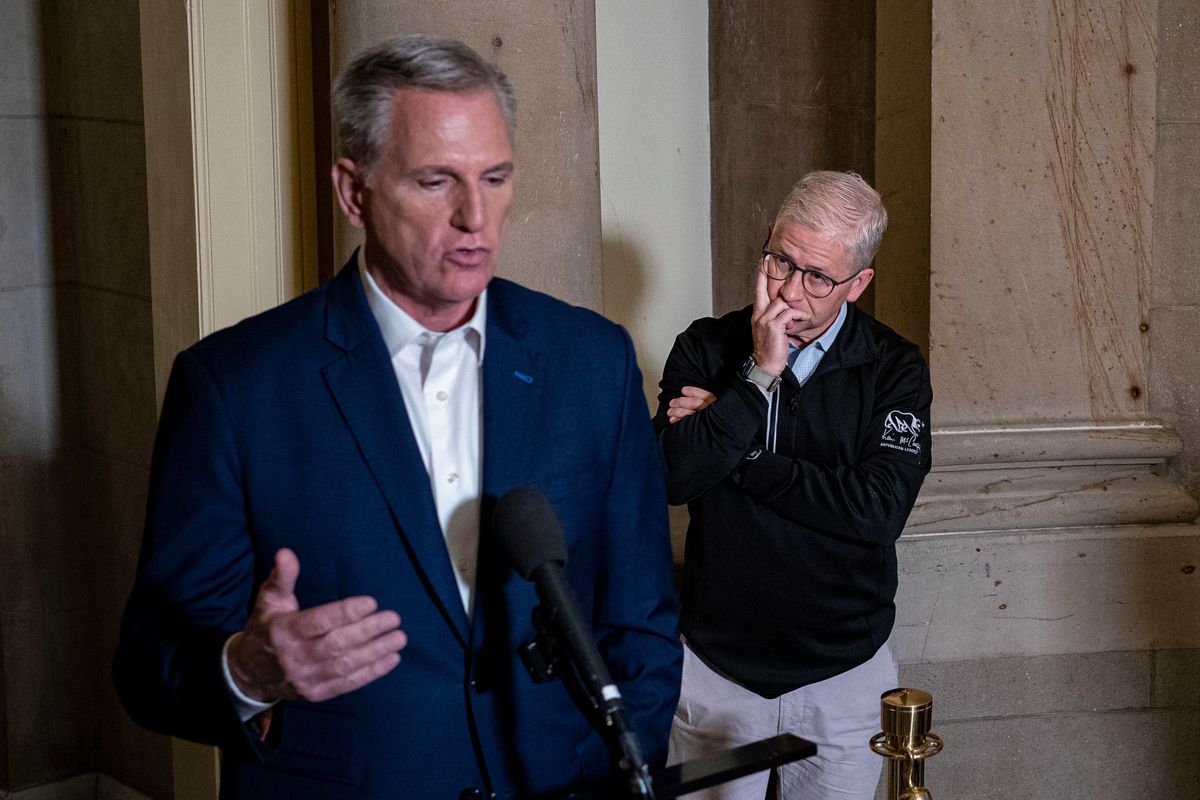

Rep. Patrick McHenry, R-N.C., right, with Speaker Kevin McCarthy, R-Calif., who McHenry said had made progress in uniting the conference since January, when a group of 20 members branded themselves “Never Kevins,” stand on Capitol Hill on May 28. (HAIYUN JIANG)

WASHINGTON – When Rep. Kevin McCarthy was short the votes he needed to become speaker in January, he didn’t browbeat his far-right Republican detractors or threaten retribution. Instead, he granted them major concessions, subjecting himself to a long, humiliating slog to win them over.

McCarthy is now facing a near-certain government shutdown and a possible move by the same faction to oust him from his post if he moves to head off the crisis. And he is turning to the same people-pleasing script, seeking to mollify a faction of his conference he privately scorns.

He has once again caved to the demands of far-right lawmakers, opening an impeachment inquiry into President Joe Biden and then agreeing to slash government spending to levels they clamored for. When that was not enough, McCarthy pushed aside a stopgap spending bill to avert a government shutdown. Instead, he bowed to the right flank’s insistence on first bringing up a series of individual yearlong spending bills loaded up with arch-conservative policy dictates – even though none had a chance of enactment.

Democrats have criticized him as the weakest speaker in history. Hard-right members continue to demand more. But members of McCarthy’s inner circle – a coterie of mostly traditional Republicans who are deeply conservative but share little in common with the hard right – argue that the speaker’s malleability is actually his strength. They say it is the only way to deal with what they regard as a nearly ungovernable majority.

“He is in the driver’s seat, but he’s also willing to ask members in the car to help him navigate,” said Rep. Dusty Johnson, R-S.D., a McCarthy loyalist. “That is not – with all due respect to other speakers – they have mostly been interested in taking everyone in the car where they wanted to go.”

Yet with a four-vote voting margin and a far right that appears bent on forcing a shutdown, McCarthy’s car has spun out of his control.

On Friday, he brought up a temporary spending bill even though he knew he lacked the Republican support necessary to pass it, simply to show the public that he tried to keep the government open – a step that would likely have been deemed unthinkable by many of his predecessors.

“Increasingly, members have been going to McCarthy to say we have to vote on it anyway,” Johnson said. “We need to show a good-faith effort to not shut down the government.”

But in doing so, McCarthy also showed his weakness. Twenty-one right-wing Republicans ultimately voted against the bill – a far bigger group than had signaled their opposition – in an extraordinary display of defiance that made it all but certain that Congress would miss a midnight deadline Saturday to keep federal funding flowing. The size of the defection underscored the speaker’s feeble grip on his conference and how willing his right flank is to go to war with him.

The group of allies advising McCarthy, a California Republican, as he navigates another difficult chapter in his speakership also includes Rep. Garret Graves of Louisiana, who has no official leadership role but has become the speaker’s crisis consigliere; Rep. Patrick T. McHenry of North Carolina, his longtime sounding board; and Rep. French Hill of Arkansas, an old-school Republican who looks and sounds like he comes from a different political party than the rebels who are tying the House in knots.

As chair of the Main Street Caucus, Johnson has been in constant contact with McCarthy since he took on the lead role in trying to work with members of the hard-right House Freedom Caucus to find a stopgap funding deal that could pass.

Rep. Jim Jordan of Ohio, a foe-turned-friend who has become a bellwether for what conservatives can stomach, has been offering advice, too. For months, he has been telling McCarthy that he needs to get the funding level of any stopgap bill as low as possible and then ask for one big policy concession from the Democrats that he can win: tighter restrictions on the border. But even that has so far proved to be a nonstarter with the rebels.

As days go by and House Republicans squander any leverage they might have to influence the Democrat-controlled Senate, choosing the least bad option has become the sad refrain of McCarthy’s closest allies.

That has left him celebrating any progress – however tiny – he can muster, such as the passage this week of a routine procedural measure that allowed several spending bills to go to the House floor for debate. Under previous speakers, winning adoption of such a measure, known as a rule, was a foregone conclusion; McCarthy has lost three in the past eight months.

“Many of you asked the question many times, could you pass the rule,” McCarthy said at a late-night news conference at the Capitol that served as a feeble victory lap for a race that was far from finished. “Now I just want to let you know that the rule has passed.”

Former Speaker Newt Gingrich, the Georgia Republican who led the GOP revolution of 1994 and tried to wield a 21-day government shutdown as a political weapon against former President Bill Clinton, said McCarthy faces a far more difficult predicament.

“I could never manage this kind of majority,” Gingrich said. “It takes patience; it takes focusing on individuals; it takes resilience. Kevin has what will be a continuing problem, and that is his margin is just too small.”

But McCarthy’s problem is not only the punishing math. Some of his colleagues say he has made so many promises to members that they simply do not trust him.

McHenry, however, argued that the speaker has made progress in uniting his conference since January, when a group of 20 members branded themselves as “Never Kevins” and had to be slowly won over with concessions.

“The speaker has proven himself to those that were strongly in his favor – the 200 that were strongly in his favor in the opening week,” McHenry said between meetings at the Capitol on Friday last week, dressed down in jeans and a T-shirt after McCarthy had sent lawmakers home for the weekend, scrapping plans for a weekend session because there was no agreement on what to do.

He noted that some of the onetime GOP holdouts, like Reps. Chip Roy of Texas and Byron Donalds of Florida, were now working with McCarthy rather than against him.

“They’re inside trying to solve problems instead of sitting across from us,” McHenry said. “The players are similar – actually the same – but where people are sitting is a little bit more toward our favor in being able to function and originate policy.”

The players may have shifted in their seats around the table, but as Congress careened toward a shutdown, it was still the far-right members of the conference who appeared to be dictating policy and procedure, with McCarthy merely reacting to their desires.

During the vote Friday, the Republican opponents rushed to put their “no’s” on the board, mostly casting their votes in the first few moments as if to emphasize that they had no qualms about going against the speaker and taking down their own party’s bill.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.