Book review: ‘Atomic Pilgrim’ author’s faith never falters, even in the face of nuclear war

President Donald Trump recently proposed a budget for cleaning up hazardous waste at the Hanford Nuclear Reservation that’s more than a billion dollars short of what Washington officials have said is needed while slashing budgets for similar projects across America.

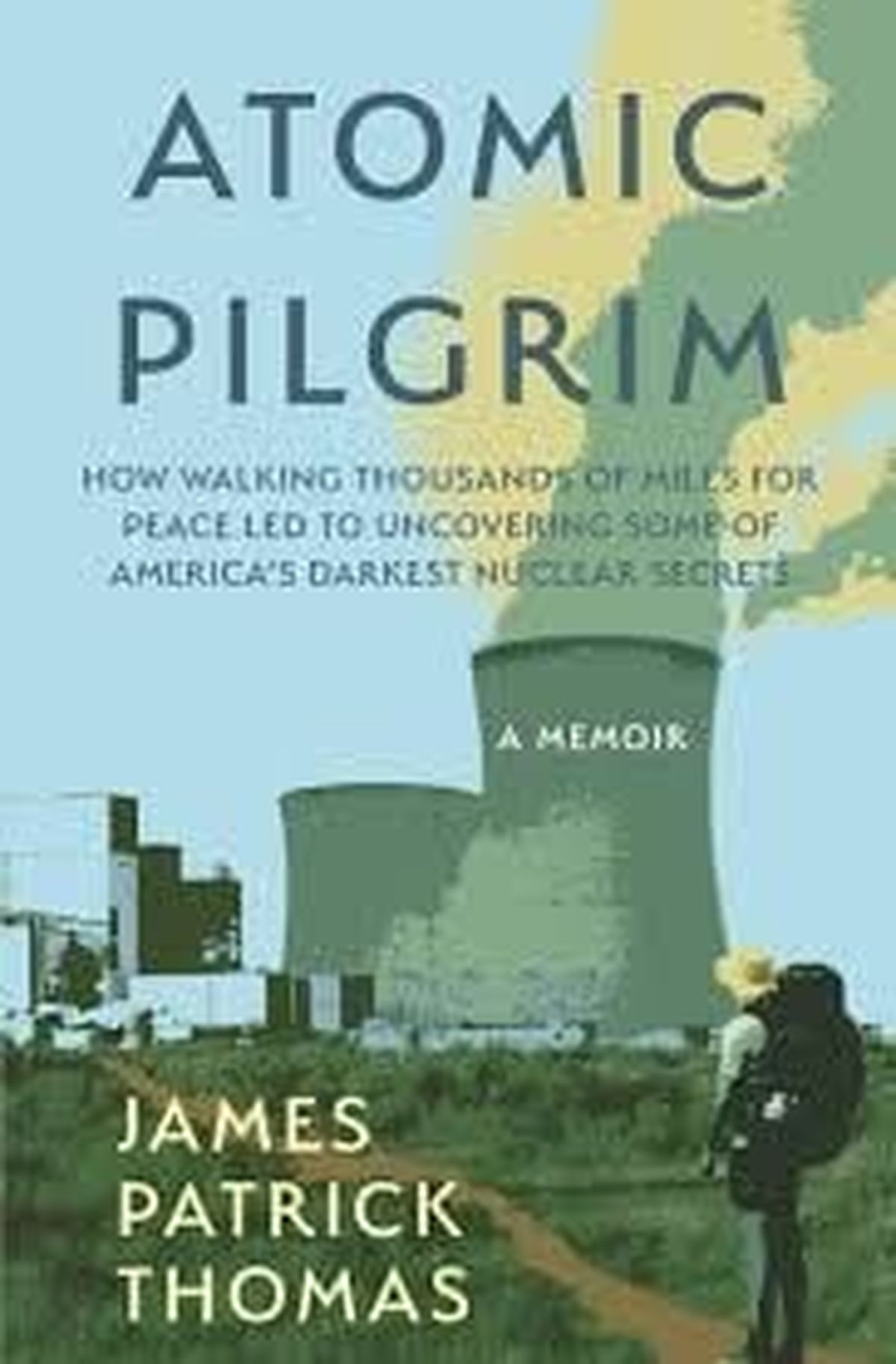

That alone is the kind of development James Patrick Thomas warns us about in “Atomic Pilgrim,” a new book that revives old fears and gives new warnings of a precarious future.

Thomas’ book is a memoir of a part of U.S. history that’s often forgotten but is in danger of being repeated.

I’ve often tried to tell my children, all grown, what it was like to grow up in the Cold War of the 1960s, ‘70s and ‘80s. It’s hard for them, because they face their own disastrous future amid global warming. But as Thomas writes, the threat of nuclear war still faces us, and needs addressing right alongside climate change. We ignore either at our own peril.

But the threat of immediate destruction of humanity was real during the nuclear arms races that began at the end of World War II with the dropping of the atomic bomb and raged for most of the second half of the 20th century.

Thomas explains those with vivid details that will give many baby boomers, and even some in Generation X, chills. We remember the “duck and cover” drills that permeated our schools, much like the active shooter drills today. But instead of someone with a gun invading our classrooms, this was an exercise – a ridiculous one at that – where we would drill on what to do in case of a nuclear weapons strike. As if sitting crouched on the floor with our hands over our heads would have done much to stave off Armageddon.

“Another ever-present reminder that the nuclear threat was real was the weekly wailing of Civil Defense sirens, every Wednesday at noon,” Thomas writes. “On summertime Wednesday, I was visiting my Aunt Jo in Spokane. I was in the backyard cleaning out the concrete birdbath under the shade of several large trees. I glanced at my watch and saw it was nearing noon. I steeled myself in the anticipation of the weekly reminder that we lived under a nuclear cloud. The fear of nuclear war was built into Cold War culture, haunting many of our waking moments.”

As a college student, inspired by Jesuit leaders and Catholic bishops, Thomas joined a walk protesting for disarmament that began in Seattle and stretched to Bethlehem. A core group of 13 pilgrims, including Thomas, and often joined by hundreds of others, walked some 6,700 miles. The path stretched from the Naval Base Kitsap-Bangor to the city of Jesus Christ’s birth.

Their goal was to call attention to the threat of destruction that the race for arms between the U.S. and the Soviet Union posed to the world.

This book is really two books in one. The first part chronicles the march for peace. It’s a slow and deliberate tale, as Thomas provides the blistering walks and personal challenges alongside the headlines of the day. The Chernobyl nuclear disaster, for instance, happens during their walk.

The second part of the book picks up after the pilgrimage, as Thomas begins his calling as a voice of peace and justice ministry in Spokane as part of the Catholic Diocese.

Part of the Gonzaga graduate’s work included filing Freedom of Information requests to the government for recently unclassified reports from Hanford. One request resulted in 19,000 pages of previously classified reports detailing Hanford’s history of collecting nuclear waste. Thomas read them all.

It turned out the biggest threat to Americans may not have been a nuclear strike from a foreign enemy, but from their own government operations.

“What we discovered shocked even the most pessimistic among us: Hanford’s bomb making had spewed extensive radioactive pollution into both the air and Columbia River since 1944,” Thomas recalls. “Even more jarring: the contamination was no accident. The releases resulted from regular factory operations, just as designed.”

“Atomic Pilgrim” documents lies told by the government and tells the stories of the people who became sick, and in some cases – including Ernest Johnson in 1952 at age 48 – died from radiation poisoning at Hanford. General Electric, the site contractor, led a coverup to hide Johnson’s cause of death, according to documents Thomas found.

Even faced with the threat of annihilation, Thomas’ faith never falters, and that allows him to keep his hope that eventually humanity will save itself.

But as this book reminds and instructs us, and as current events informs us, there’s still much work to do.