Large Spokane Valley development over a decade in the making in limbo again

Painted Hills Golf Course’s driving range is all that remains of the former golf course. (Kathy Plonka/The Spokesman-Review)

A proposed development that would bring up to 584 new residences to Spokane Valley may not be move forward, despite receiving city approval last year.

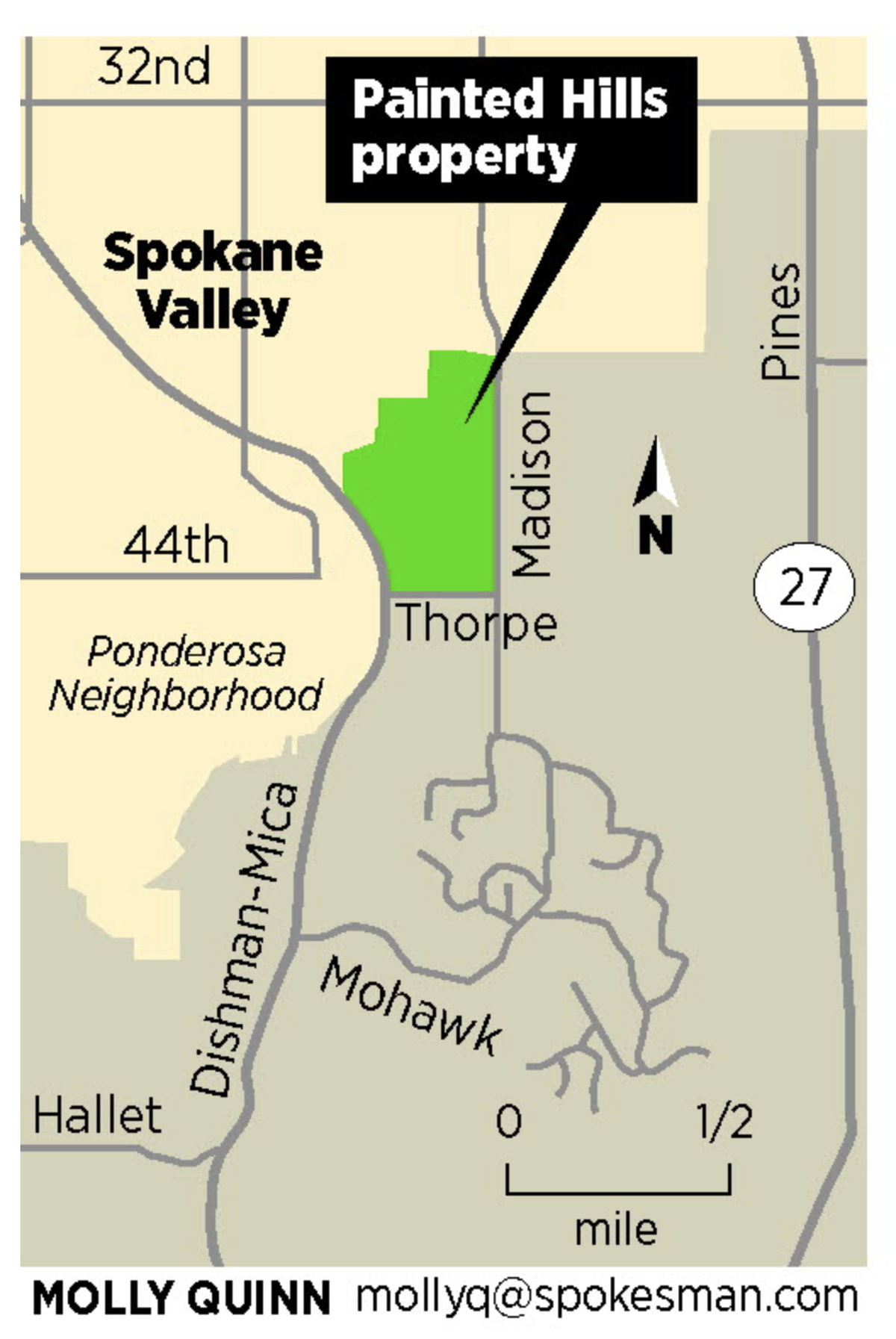

Spokane Valley’s contracted hearing examiner Andy Kottkamp’s approval of the Painted Hills development along Dishman Mica Road last March appeared to mark the end of more than a decade of back and forth between city officials, community members concerned about the neighborhood’s appearance and NAI Black, the developers behind the project.

But recent rumblings that the Spokane County Board of Commissioners might not support a condition of the project’s approval have put it in limbo, again. And the CEO of the company behind the project says the addition of that condition was a “completely disingenuous” way to derail it.

Dave Black, CEO of the company that shares his name, bought the nearly 100-acre Painted Hills Golf Course at auction in 2013, with the intent to convert the property into a mixed residential and commercial development with homes, apartments and local shops.

Following Kottkamp’s decision, the path to Black realizing that goal seemed clear, so long as the company met the requirements to build laid out by Kottkamp.

Black argues the decision allowed Spokane Valley to “stop our project by approving it,” and has filed a lawsuit against the city to recuperate damages related to the project’s decadelong delay and to refute one of Kottkamp’s conditions of approval.

“It was completely disingenuous,” Black said.

The condition with which Black and his associates take umbrage is Kottkamp’s requirement of a formation of a flood control district on the site, a request that originated with the city.

A large chunk of the property lies within a floodplain for nearby Chester Creek, and neighbors have long worried any action taken to mitigate seasonal flooding could push that flood risk onto their properties.

NAI Black has planned to install a large, multifaceted flood control system, which includes a network of culverts and pipes directing water to swales, an infiltration pond and an empty 4-acre field when needed. In addition, developers would dump around 330,000 cubic yards of dirt atop the old course to bring it above the floodplain – the equivalent of more than 21,000 commercial dump-truck loads.

Spokane Valley argued the district was necessary to oversee and maintain the system that developers plan to install on the historic flood site, as they did not want the responsibility to fall on the city.

Spokane Valley City Manager John Hohman said in a written statement Tuesday that the city is “committed to actively seeking the creation of additional housing opportunities, prioritizing compliance with environmental and developmental regulations, and addressing flood control and land use concerns in our community.”

NAI Black, on the other hand, had proposed a homeowners association to take responsibility for the massive system.

Hohman said in addition to Spokane Valley, the county and the Federal Emergency Management Agency all expressed concern over the long-term viability of a homeowners association taking the charge during the project’s environmental review process.

The lawsuit, which aimed to do away with the requirement of the flood district, is still working its way through Spokane County Superior Court.

State law requires a board of county commissioners to approve the formation of a flood control district, either by their own volition or through the directive of voters in the form of a petition “signed by twenty-five percent of the electors within a proposed zone,” as worded in the Revised Code of Washington.

Hohman said the city would support NAI Black’s effort to form a district, as the county board has indicated it may not take action on its own.

At a county commissioners informational meeting Tuesday, Spokane County engineer Matt Zarecor recommended against forming the flood control district, citing the administrative burdens of forming and managing the district, like collecting fees, directing maintenance and the county’s liability in the event of a disaster.

Zarecor also pointed to the location of the flood systems, which is within Spokane Valley city limits, and how the county would be placed in the middle of disputes between the city and the neighborhood HOA.

Commissioner Al French said he and Commissioner Josh Kerns met with Spokane Valley officials recently, and made it abundantly clear the county is not interested in forming the district “at all.”

“One thing we did reiterate fairly clearly is the whole idea of a flood control district was off the table, that there was no support to do that at all,” French said.

In a written statement, Hohman said the condition of the formation of a district was developed after an “extensive environmental review process and multi-day hearing,” and urged the county commissioners to “support the wishes of the neighborhood and align with the hearing examiner’s findings.”

French and Zarecor both posited that the city or the county could manage an alternative system instead, like a drain water account. Residents of the development would be charged a fee, and the municipality would oversee all maintenance for the flood control system.

Zarecor argued it’s the “right-sized solution” as it ensures fees are collected through special assessments on property tax statements, without the administrative burdens associated with a flood control district.

“It gives the assurance that everybody wants: to make sure that the money will be there to maintain facilities,” Zarecor said.

The county already has around a dozen similar accounts in place and could take on another, French posited.

Chair Mary Kuney responded that the county would still be overstepping into the matters of one of its cities.

“Even this puts the county in the middle of it,” Kuney said.

The city would still be reliant on the county even if it opted for the alternative, Hohman argued, as state law only grants the power to use tools like flood control districts and drain water accounts to county leadership, he said.

“As a separate corporate entity that can sue and be sued, the flood control district alone would bear the responsibility and liability of maintenance, whereas a drain water account puts the onus on the County to ensure proper maintenance and operation,” Hohman added.

Black said he’s holding out hope for a path forward, mainly through a settlement with Spokane Valley . He said the property is one of the last few areas of the growing city that can still be developed amid the nation’s housing crisis, and admonished Spokane Valley leadership for “denying private property rights.”

“Fortunately, there’s no bad real estate; you just got to live long enough,” Black said with a chuckle.