The Seaweed Solution: From concrete, bricks to cattle feed and bacon’s doppleganger

It can be used to wrap sushi rolls or serve as a pestilent, sometimes smelly, nuisance for beachgoers. But is that really all seaweed is good for?

There has been a rising tide of interest in the best ways to use the versatile, ubiquitous aquatic plant, of which there are 12,000 known species. For several researchers and interested businessmen, many of whom are located in the Pacific Northwest, seaweed has the potential to save the world. It can replace concrete, plastic wrapping and even tastes like bacon when cooked the right way.

Concrete, just like seaweed, is everywhere. It fills in the cracks of the sidewalk, builds the foundation for skyscrapers and holds up monuments created thousands of years ago.

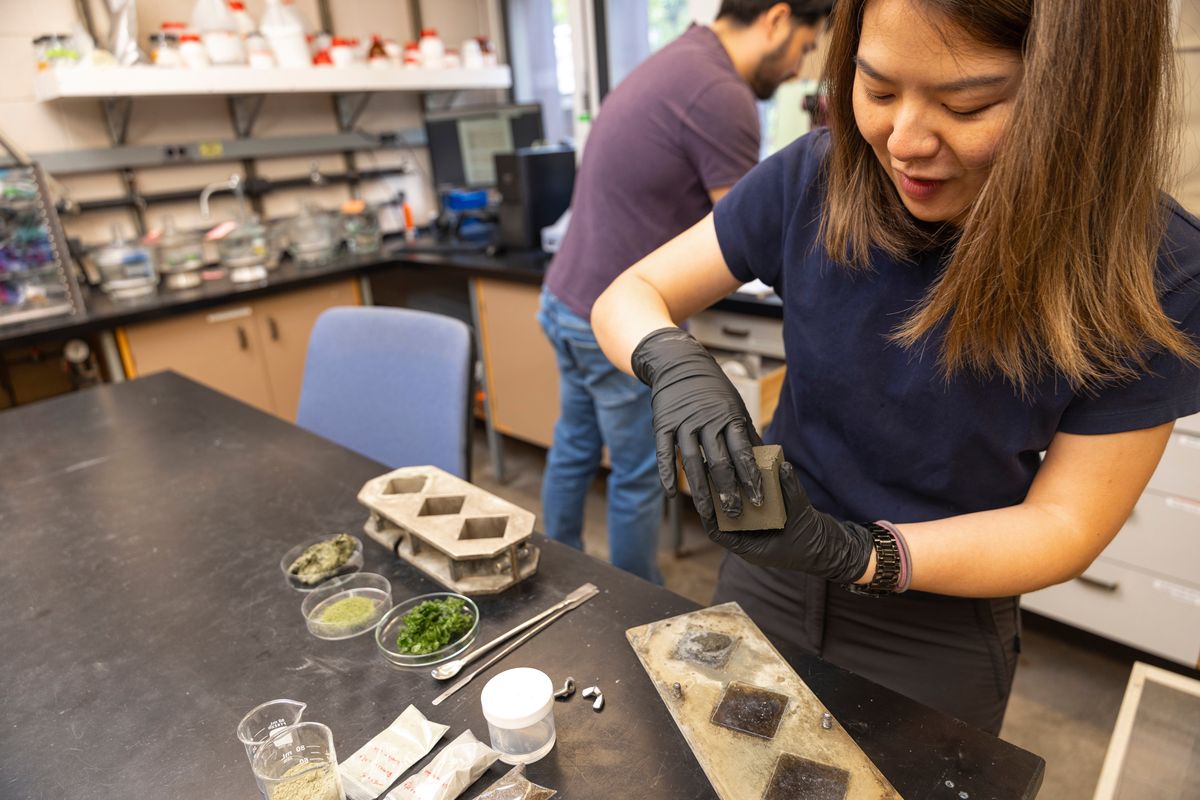

But cement, the key ingredient in concrete, is responsible for 8% to 10% of all worldwide carbon dioxide emissions, according to the World Economic Forum. That is why researchers at the University of Washington, in partnership with Microsoft, have developed a new kind of concrete with seaweed as the secret ingredient. By taking dried, powdered seaweed and mixing that with cement, the team was able to manufacture a seaweed-strengthened cement that has a 21% lower carbon footprint, while still performing on an industrial scale.

“We need to make significant changes, or every year is going to be worse than the last in terms of weather and climate change,” said Eleftheria Roumeli, the lead researcher and assistant professor of materials science and engineering at UW. “So it’s very simple. The motivation is very clear for me.”

Roumeli said her lab focuses on studying organisms like algae, seaweed and food waste to retrieve what is useful from them. They have been working on different iterations of this project, including examining seaweed’s unicellular cousin, micro algae, for the last six years. Seaweed was a natural choice because it pulls carbon from the air and locks it away during photosynthesis. Compared to land plants, Roumeli said aquatic plants are considerably better at absorbing carbon dioxide.

But in order for Roumeli and her team to get the right mix of seaweed incorporated into cement, they first needed some help from a familiar tech behemoth.

Kristen Severson, a principal researcher at Microsoft Research, made an artificial intelligence, or a machine learning model, that could help Roumeli and her team identify the optimal mixture of seaweed and cement. This machine learning approach reduced the amount of time they had to spend on the experiment by more than 100 days to only 28 days.

Ulva, sometimes known as “sea lettuce,” is an edible type of seaweed that Roumeli used for this experiment because she believed its complex cellular structure would be particularly adept at reinforcing cement. People around the world are incentivized to grow ulva because it grows fast, soaks up carbon, is a good source of protein and can improve water quality by removing heavy metals.

Roumeli said that lowering the carbon footprint of cement while not sacrificing strength were the two criteria they built their experiment around. Roumeli verified the hardy durability of the seaweed-cement by subjecting it to compressive strength tests.

“The paper is not necessarily about these materials,” Roumeli said. “It’s giving the framework for other people, as well as us, to explore further. Now we have an optimization tool that if you use it, it shouldn’t take you years to get to nicer combinations.”

She said their team wants to look at other kinds of seaweed to see if they can put a bit more in cement and still have construction-grade material. Sargassum is an invasive, smelly species of seaweed that Roumeli identified as the next species they are focusing on.

Stinky sargassum for building homes

The rotten-egg smell of sargassum has plagued communities from the shores of West Africa to the beaches of Mexico the last few years. While sargassum serves as a breeding ground for turtle hatchlings and a safe space for hundreds of species of fish in the depths of the ocean, once it washes ashore it begins to rot and emit hydrogen sulfide, a chemical compound that is toxic to humans and many animals.

In 2018 , the cost to clean up decomposing sargassum across the Caribbean reached $120 million, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. This figure does not include money lost from tourism and fisheries.

A study published earlier this year in Nature Communications reported the huge sargassum boom is because of changing wind patterns, ocean currents and nutrient-rich waters. Much of the increase in sargassum can be blamed on warmer water temperatures because of climate change paving the way for more suitable sargassum habitat in the 5,000-mile stretch of tropical Atlantic Ocean known as the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt.

Omar Vazquez is an entrepreneur and innovator in Mexico who has turned sargassum into bricks to build houses. Vazquez and his team can make approximately 2,500 bricks per day with only one machine, which was designed to make adobe bricks, and 20 tons of wet sargassum. After drying in the sun for four hours, the rectangular slabs from under the sea no longer stink and are ready to be used. The “Sargablocks” that Vazquez patented are 40% sargassum and 60% other organic materials.

The houses that his company, Vivero Blue-Green, build can withstand the elements for around 120 years. But Vazquez and his crew aren’t the only ones examining new ways to use smelly sargassum.

Seaweed biorefinery

The sargassum biorefinery, or SaBRe for short, is a coalition of various research institutions and universities, including Princeton and Rutgers, looking to develop processes and technologies for converting sargassum into usable products. A biorefinery converts raw biomass material, sargassum in this case, into a product, just like how an oil refinery would turn crude oil into fuels like gasoline or diesel.

“A major goal here at SaBRe is to develop localized processes,” said Rebecca Garcia, a second-year PhD student at Rutgers University. “So we’re developing these processes in our lab spaces right now, but obviously we want to be able to scale-up at some point, and so that would involve working with local communities and strengthening local economies.”

Garcia works in professor Shishir Chundawat’s lab extracting carbohydrates from sargassum to create products, including biofuels and biopharmaceuticals. SaBRe is split into six or seven different divisions, each focusing on a different aspect of turning raw sargassum into something useful. Garcia said SaBRe has 30 to 40 professors, students and innovators from around the world working together.

Fuels, chemicals, fertilizers, pharmaceuticals and more valuable commodities are possible from this stinky seaweed, which SaBRe dubs the “feedstock of the future.” Schmidt Sciences and the Foundation for Food and Agriculture Research has committed up to $47.3 million over five years toward this effort. Questions remain about how to transform their efforts into a model to attract investors.

Plastic wrappers, spoons and bacon-flavored seaweed

Picture bacon. Now, picture seaweed. Mentally correlating the slimy marine algae with crispy, sizzling, delicious bacon could be a jarring juxtaposition.

But for Oregon State University professor Chris Langdon, anything that tastes remotely like bacon, even if it once had a slick texture and swayed under the sea, is a sought after delicacy. Palmaria palmata, or what’s colloquially known as dulse, is a red seaweed with high nutritional value. When fried, it also tastes like bacon.

“This was based on a remark that was made by some customers in a Portland restaurant that was deep frying dulse and serving it as an hors d’oeuvre or as the accompanying meal,” Langdon said. “So that little phrase, ‘tastes like bacon,’ kind of went around the world, and a huge amount of news activity associated with that. Some people got the wrong end of the stick and thought that we had somehow crossed seaweed with pigs.”

On a scale of 1 to 10 on the “taste-like-bacon” scale, Langdon said fried dulse rests around a 6. It is crispy, salty and savory when deep fried, but is lacking the fatty flavor prominent in bacon. Still, Langdon said dulse is rich in proteins, antioxidants, minerals, vitamins which makes it a great replacement for vegans and people with religious restrictions.

Langdon has been examining potential uses for dulse since the 1980s. He said that as temperatures rise, fresh water, which makes up about 3% of the Earth’s total water, will become less readily available. But seaweed only needs salt water and sun light, and it is mostly insulated from temperature extremes in the ocean.

“I was sitting at home here in Oregon and listening to a Filipino newscast on television where they were reporting on the (bacon) story, and most of it was made up, not based in fact, but it was fascinating to hear the story had reached even that part of the world,” Langdon said. “At the time, I was inundated with phone calls, and I got venture capitalists with $100 million to spend wanting to talk about investing in it. So, there’s a huge amount of interest now in seaweed, and I think that is going to grow as we go into this century.”

Of all of those venture capitalists, Langdon said, not one invested.

A couple of years ago, Zhongfan Jia, a professor at Flinders University in Adelaide, Australia, worked with a team to create a grease-resistant fast food wrapping made of seaweed. Whether it is burgers, fries or any other oily fast-food hankering, the wrappings of these foods are usually laminated with a layer of thin plastic. When this material, which is often made of synthetic polymer, goes to get recycled, it cannot biodegrade. Instead, it breaks down into smaller pieces, or what are called microplastics.

But the wrapping they made in less than a year that could repel grease, oil and water never went further than the confines of his lab. He said the company that supported the research was an intermediary “broker” company that stopped funding his work once they could not find anyone to buy the formula for the seaweed wrapping. Companies often want fast results they can sell in a hurry. This mindset, Jia said, is “against the nature of the research.”

While using seaweed for cement is vastly different than using it for plastic wrapping, seaweed’s multifaceted capabilities should not be ignored. Other companies are looking at turning seaweed into fishing gear, compostable polybags and even spoons, among other things.

Cow Burps and Seaweed

A study published in December 2024 revealed that feeding seaweed to grazing cattle cuts methane emissions by almost 40%.

Livestock accounts for 12% of global greenhouse emissions, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The largest portion of these emissions come from cows burping up methane. By 2050, the demand for livestock is expected to increase by 20%, which makes efforts to reduce methane emissions crucial in the fight against climate change.

Ermias Kebreab, an associate professor of animal science at the University of California Davis, said his team infuses red seaweed with molasses and different kinds of oils to make it taste better for cattle.

He said red seaweed naturally has an ingredient called bromoform that inhibits the enzyme that produces methane. In the lab, Kebreab said the cows that ingest red seaweed in a controlled environment reported a reduction in methane emissions by up to 90%. Kebreab and his team are still in the initial phase of their research, but he said around four startup companies are trying to commercialize their work.

“Cows are picky like people,” Kebreab said. “They eat what they know. Something new, they’re a little suspicious. But then once they get used to it, they’re fine.”

Seaweed Farms of the Future

Chuck Toombs’ business, Oregon Seaweed, has two dulse farms in Garibaldi and Bandon. Instead of the traditional method of growing seaweed where seeded ropes are suspended horizontally in the ocean, he is growing his seaweed in 1,500-gallon, 10-foot diameter tanks on land.

“I thought that doing it in tanks at a large scale would be better, because you could feed it, and you could harvest it, and you could watch it,” Toombs said.

Being able to monitor water temperature, pH levels, water quality and other factors through an on-land method is an approach that few U.S. seaweed farmers have tried. Not to mention, Toombs and his three employees can conveniently scoop up their seaweed with a net, which is considerably easier than traditional methods. With 30 operational dulse tanks across their two locations, Oregon Seaweed is the largest land-based seaweed farm in the United States.

Toombs came across the power of dulse while teaching business classes at OSU. For his class of about 400 students, he decided to make a Shark Tank-style assignment where students found and marketed technologies that faculty and professors at Oregon State had developed.

It did not take long for Toombs to find Langdon working on dulse. Toombs said around this same time, the popularity of kale saw a huge spike because Gwyneth Paltrow promoted kale on Ellen DeGeneres’ TV show and Beyonce wore a kale shirt in public. But when Toombs tried kale, he thought it tasted terrible.

“Why can’t (dulse) be the next kale?” he asked Langdon.

It didn’t take very long for Toombs to see the potential in dulse, which led him to creating Oregon Seaweed in 2015. Now a decade later, his business still is not profitable, but that is not because of lack of demand. Around 80% of Toombs variable cost comes from electricity. He said his business model is more akin to a data center than a traditional farm because he only needs sunlight and energy to keep optimal conditions in the tanks. Because of this, he has made numerous trips to the state senate asking them to grant him the same price for electricity as all the data centers popping up. So far, he has not had much luck.

“The real economic choice in 10 years when people wake up is, what are you going to want?” Toombs said. “Are you going to want protein or are you going to want data? That’s going to be the tradeoff in the future.”

Toombs said if he got the same price for electricity that the data centers get on average, he could sell dulse protein at 20% below the cost of soy protein without having any carbon footprint. He also said dulse grows about 50 times faster than soy beans. He believes he is revolutionizing the way that seaweed is grown and is disappointed more people haven’t caught on. He has had visitors from foreign countries, like Korea, check out his farms and game plan for something similar, but has received little attention from people in the U.S.

Toombs wants to scale-up his business even more, but in order to do that he estimates he will need between $5 million to $10 million. Ideally, he would like a 50-acre property, with 1,000 tanks and a processing facility. This is a dream he hopes to make a reality in the next couple of years, as the popularity of dulse grows. Along with snacks and restaurant items, dulse is also used in pet food because it has an amino acid called taurine that is crucial for the well-being of cats.

Toombs believes he has found the plant of the future.

“I believe using market forces, you can create a wonderful environment for people to live in,” Toombs said. “I see it as a gift to the world”