Increased odds of lightning-caused fires expected in the near future, according to new study from WSU researchers

Ruinous fires across the West often lead to smoke-filled days with flames tearing through large swaths of natural land.

While most of these fires are started by people, many fires start because of lightning strikes.

It’s common for fires started by lightning to tear through more acreage than human-caused fires because they often happen in remote areas that are difficult for crews to reach.

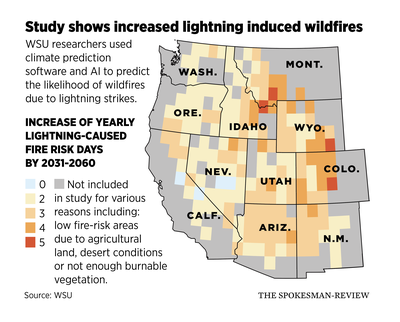

A new study from researchers at Washington State University offers projections of lightning across the Western United States between 2031 and 2060 using a subset of artificial intelligence and global climate modeling. The lightning predictions were then matched with future wildfire risk to discover the changes in daily risk of lightning-induced fires.

Their results show that an elevated risk of lightning-caused wildfires is supposed to spark across 98% of the Western United States. Depending on the region, an average increase of between four and 12 days per year of lightning can be expected. For example, the Bitterroot Valley of Western Montana stretching to the Idaho border is predicted to see one of the largest increases in both lightning and wildfires.

Much of the Inland Northwest is expected to see an increase in days of lightning, but that doesn’t necessarily correlate to more days of fire.

Dmitri Kalashnikov, a current post-doctoral fellow at the University of California-Merced, and the lead researcher on the project while he finished his Ph.D. at WSU, said they couldn’t model or predict much of a change for Spokane and surrounding areas because the majority of land here is agricultural, which is not considered a risk for lightning-caused wildfire ignition.

Kalashnikov used a subset of artificial intelligence called a convolutional neural network to predict the future. He compared setting up a network to how Waymo or Tesla might program self-driving cars.

A self-driving car knows what another car looks like, what a pedestrian looks like and even knows what color a stop sign is. But in order to get the AI to that level of comprehension, it has to be shown thousands of images so it can learn how to differentiate.

“So in my case,” Kalashnikov said, “instead of giving it images of stop signs or pedestrians, I gave them a whole bunch of daily weather maps for a 28-year period. Some of those days had lightning, some of those days did not have lightning.”

Kalashnikov then had the network assess what the weather patterns looked like for days with and without lightning using observational data available from the past alongside three meteorological variables favorable for lightning formation. Once the neural networks were trained, he then applied it to a global climate model that simulates past, present and future conditions for ocean, land, atmosphere and more.

“It predicts these future days will have lightning, and then these other future days won’t have lightning because it learned that from historical data,” Kalashnikov said.

The neural network models analyzed a grid cell of 1 degree by 1 degree across the whole Western United States for every single day starting in 2031 and ending in 2060. Each grid cell is roughly 62 miles on each side, Kalashnikov said. Because the 1-degree box is such a finer scale of examination than in previous studies, Kalashnikov and his team’s approach is the first of its kind when it comes to predicting future lightning. Other studies have looked more broadly, but Kalashnikov said this is the first study of its kind to look at lightning occurrences in each single grid box.

In addition to observational data from the past, three meteorological variables conducive to lightning were inputted to more accurately predict lightning in the future.

When these variables are combined with historical lightning data stretching back 30 years, the computer models can better learn to predict lightning. Once the machine -learning program has a good grasp on what conditions lead to lightning, then it is introduced to the Community Earth System Model so it can map what areas of the Western United States will see an increase in days with lightning.

The other part of this project, once the predictions for cloud-to-ground lightning were made, was to combine the data they got with the projected Fire Weather Index for each day to determine which days were likely to be lightning-induced wildfire days.

Having a grasp of what days and what areas are susceptible to lightning-induced wildfires is important to understand for citizens, researchers and firefighters alike as climate change becomes more prominent.

The real value, Kalashnikov said, isn’t from these simulations being able to predict a single day, or even a single year; it comes from running the simulation over 30 years and then summarizing the data. The more information there is available about potential risk for a certain area, the more prepared policymakers, fire crews and the average citizen can be when a fire does break out, whether that’s in the summer of 2026 or the summer of 2059.

“If people are informed about potential future increases in these lightning-caused fires, that can hopefully start conversations,” Kalashnikov said. “Hopefully it’ll spur some kind of proactive actions, whether that’s funding for fire suppression, whether it’s policy changes around allowing more prescribed fires, which will dampen the risk of actual severe wildfires.”