Researchers at University of Idaho help discover small moon orbiting around Uranus

For researchers at the University of Idaho, spotting a moon 6 miles wide orbiting Uranus, a staggering 1.8 billion miles from Earth, may actually be easier than finding a white cat in a snowstorm.

A team of eight scientists from various institutions, including UI professor Matthew Hedman , harnessed the observational power of the James Webb Space Telescope to find Uranus’ 29th known natural satellite, or what’s known more colloquially as a moon.

“JWST looks in the infrared, which is longer wavelengths then our eyes can see,” Hedman said. “If you look at the visible, like Hubble does or even Voyager, the planet is extremely bright, which makes it even harder to see faint moons.”

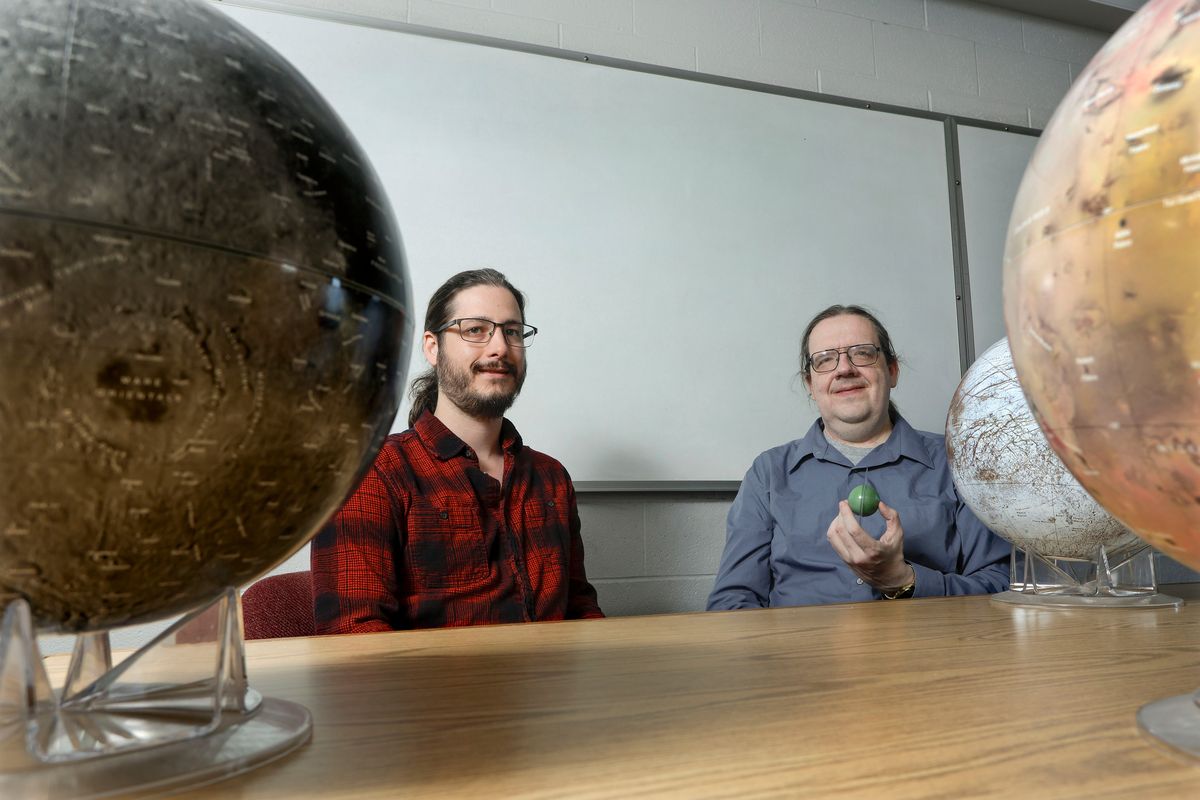

Using the Webb telescope’s near-infrared camera, scientists led by the Southwest Research Institute captured 10 40-minute, long-exposure images of Uranus in early February. Since then, researchers like Hedman and University of Idaho graduate student Jacob Herman have been studying different properties of the new moon, plainly named for now S/2025 U1. The other 28 moons of Uranus are commonly referred to as the “literary moons” because every one is named after a character created by either William Shakespeare or Alexander Pope.

Through detailed examinations of the 10 long-exposure captures, the team was able to confirm the 6-mile-wide object was a moon because its trajectory around Uranus was consistent with the laws of gravity and it was roughly the same brightness in each image. Even when Voyager 2 flew past Uranus in 1986, it discovered 10 moons, but S/2025 U1 was so tiny that it went undetected.

Uranus’ newly discovered moon is about 35,000 miles from the center of the planet. Of the 29 total moons, there are only five major ones. Another 10 moons are called irregular, as they have highly elliptical, large, inclined orbits that go in a retrograde, or clockwise in this instance, direction. Many scientists believe these irregular moons were once asteroids or objects from the Kuiper Belt that got sucked into Uranus’s orbit. The moon discovered with UI’s help joins an armada of 13 smaller inner moons that all orbit the major moons and near the planet’s rings.

Much like its more notable ring-bearing neighbor, Uranus has planetary rings stretching around it. Hedman said Uranus has nine brighter rings that can be seen relatively easily from the vicinity of Earth. Another 12 or so rings are more narrow and harder to see.

But unlike its ringed gas giant companion, Hedman said the rings of Uranus are significantly smaller, darker and narrower than Saturn’s “broad sheet” of rings. The mystery of Uranus’ narrow and contained rings has baffled scientists like Hedman for a long time. A prevailing astronomical theory is that many of the moons of Uranus act as “shepherds” for the rings of the planet.

“There’s one of the rings that might be in a place where the gravitational tugs from the moon tend to build up over time and help keep the material confined,” Hedman said. “But whether that works or not depends really sensitively on how fast the particles of the rings move compared to how fast the moon moves around.”

The perplexing mystery of gravitational influences in the Uranium system is not limited to how the moons act as herdsman for the rings but expands to how the moons interact with one another.

Gravitational pulls and the close proximity means that the moons of Uranus perturb each other in ways scientists don’t fully understand. Some of these interactions most likely resulted in collisions in the past, which would provide evidence for much of the material in Uranus’ rings.

“When people try and calculate how their orbits will change over time, those perturbations lead to the moons crashing into each other on timescales of one to 100 million years, so way less than the age of the solar system, which means some of these moons have probably crashed into each other sometime in the past,” Hedman said.

The ice giant Uranus is the seventh planet from the sun and is about 19 astronomical units away from the sun. One astronomical unit is the distance from the sun to the Earth.

Uranus was first discovered by British astronomer and composer William Herschel in 1781. Upon discovering the new planet, Herschel wanted to name it Georgium Sidus, which is Latin for “George’s Star,” to pay homage to King George III of Britain. Many scientists outside of Britain did not love that idea.

German astronomer Johann Bode proposed the name Uranus to follow the tradition of naming planets in the solar system after Greek and Roman gods. Uranus is the Latinized version of the Greek god of the sky and grandfather of Zeus, Ouranos.

Like the rest of the gas giants in our solar system, Uranus dwarfs the four terrestrial planets, including Earth, in size – so much so, that scientists believe 63 Earths could fit into one Uranus. NASA estimates that if the Earth was the size of a nickel, then Uranus would be about the size of a softball.

The famous pale blue-green hue of the planet can be attributed to methane gas in its atmosphere. More than 80% of Uranus’ mass is made of a dense stew of “icy” materials, like water, ammonia and methane.

Wind speeds on Uranus can reach up to 560 mph. Uranus also holds the record for the coldest temperature ever measured in the solar system at -371.56 degrees.

Each pole of the pale planet takes turns being in complete darkness for 42 years at a time over the course of the 84 years it takes for the planet to go around the sun. The four-decade lightless abyss on half of Uranus is because of its extreme axial tilt of about 98 degrees. Earth’s tilt is only 23.5 degrees. Because of Uranus’s significant tilt, the planet spins on its side like a rolling ball rather than rotating around like the average planet does.

“That’s one of the biggest mysteries of the Uranus system to date,” Hedman said. “The current theory is that, when you’re early in the solar system’s history, something planet-sized knocked Uranus on its side.”

Hedman was just a kid in the 1980s when the Voyager missions were streaking their way past the last few planets in our solar system, including Uranus. The stunning photos that the Voyager missions returned to Earth sparked a lifelong passion for him.

Before coming to the University of Idaho in 2013, Hedman was involved in the Cassini-Huygens mission that orbited Saturn from 2004 to 2017, before it free fell into the ringed planet’s atmosphere. His job for the Cassini mission was to analyze and make sense of the data the spacecraft captured.

As the Cassini mission started to wind down, Hedman’s focus shifted from Saturn to Uranus, which he said has the next most complex system of moons and rings in our solar system.

For Herman, who has another four or five years before he gets his doctorate in physics, the opportunity to study the outer solar system using information from the Webb telescope is a dream come true. Herman said he wanted to be a naval architect for a long time, but fell in love with physics after taking a break from mechanical engineering.

Herman is analyzing how the moon orbits around Uranus. He is also looking at the moon’s color in different wavelengths using the Webb telescope’s near-infrared camera to learn more about the composition of the moon.

While he said he can’t give away too much information about the surface of S/2025 U1, Herman did say it’s very similar to Uranus’ other moons. Similarly, Hedman said that they don’t know the exact make-up of the moon, but said it’s the opposite of fresh snow. Charcoal is the closest thing on Earth that Hedman could compare the dark material on the moon to.

NASA’s website states all the other inner moons of Uranus spotted by Voyager 2 are approximately half rock and half water ice. But Hedman said many of them are dark, as they only reflect 5% to 10% of the light shone upon them, which means the moons are probably mostly made of carbon compounds. Carbon is considered the basic building block for life.

Operated by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the Webb telescope only accepts about 10% of all the requests made through the General Observer program. This makes Hedman, Herman and the lead scientist in the Southwest Research Institute’s Solar System Science and Exploration Division, Maryame El Moutamid, a lucky chosen few.

Hedman and Herman said they will continue to research their newly discovered moon until they can’t learn anything else from it. As is a common occurrence in science, once some answers are found, more questions arise.

“In order to understand where we are, we have to understand what’s out there,” Herman said. “We’re the modern day explorers trying to understand what’s going on beyond here on Earth.”