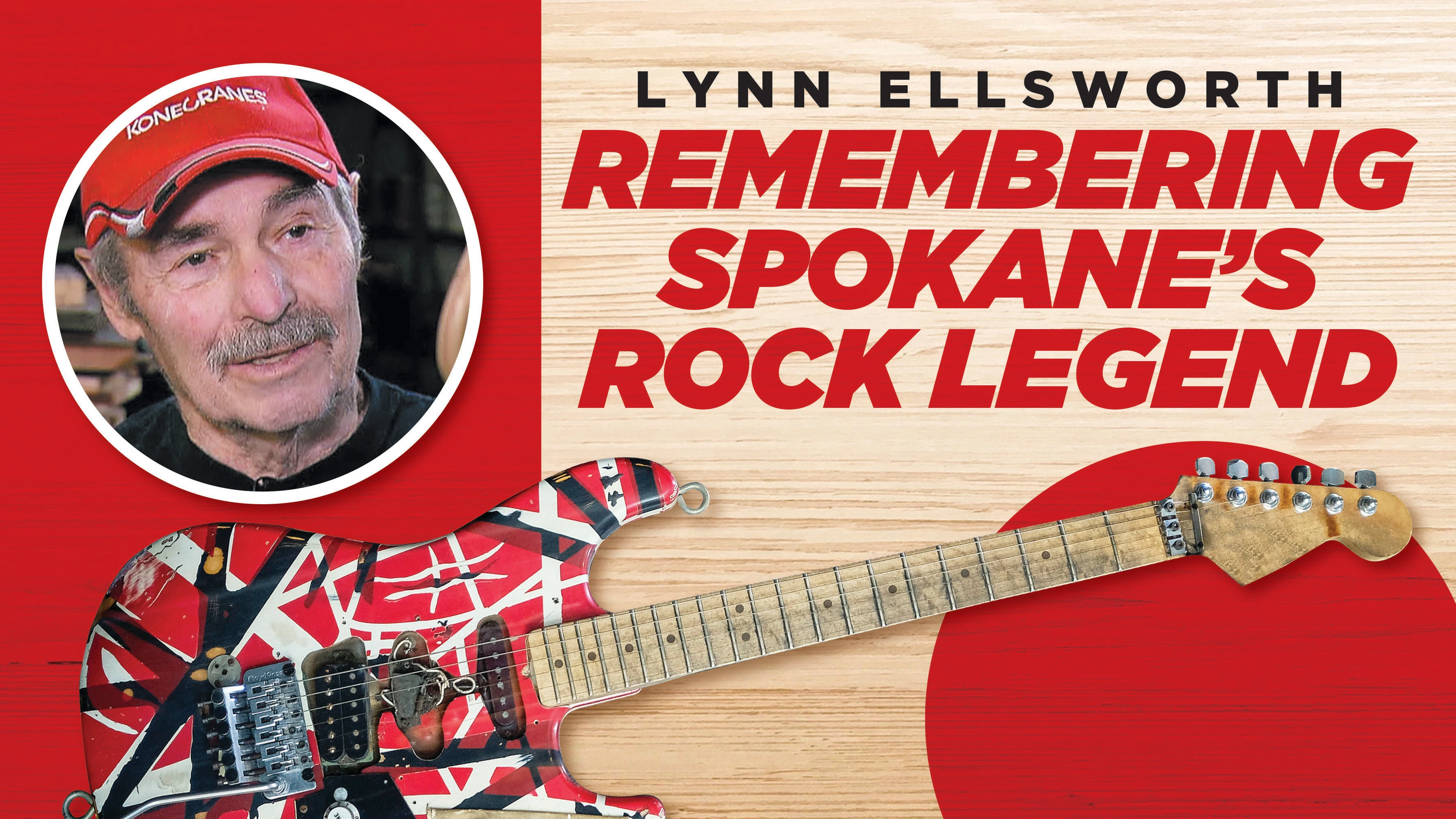

Lynn Ellsworth, a renowned guitar-maker whose work was purchased and played by some of the biggest rock -and -roll musicians of the last several decades, died April 27. He was 81.

His instruments were played by guitar legends ranging from Pete Townsend to Eric Clapton to Joe Walsh to Billy Gibbons. But it was Ellsworth’s ties to one of the most famous instruments of all time – Eddie Van Halen’s completely beat-up, red-and-white-striped guitar, often referred to as “Frankenstrat” – that helped make the Washington native’s custom guitars such highly sought-after instruments.

But Van Halen purchased a guitar body made by Ellsworth long before his namesake band hit it big.

On the cover of Van Halen’s 1978 debut album, Eddie Van Halen is holding a white guitar with black stripes that looks a lot like a Stratocaster. Except it wasn’t a Fender Stratocaster. It was the guitar body Ellsworth had crafted. It also was the guitar the Eddie Van Halen played on the album.

Van Halen loved to modify that guitar, and even painted it several different ways before it ended up primarily red with black and white stripes.

Ellsworth’s Eastern Ash guitar body was a key part of an instrument so famous that a copy of it is in the Smithsonian Institute’s National Museum of American History. The original is considered a priceless piece of art and was even put on display at the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art in April 2019 in an exhibit of the most important instruments in rock ’n’ roll history. Wolfgang Van Halen, Eddie’s son, said in a recent interview the guitar was “locked down and safe in a way that if the world ended it would still be OK.”

When Ellsworth retired in 2012, he decided he was going to move to Spokane, a place he said he always loved to visit, and knew would be the last place he ever lived. Yet, he never stopped making guitars. Though famous guitarists would still reach out to him, Ellsworth’s guitars began being purchased by more and more notable guitarists across the Pacific Northwest.

Many of those people considered Ellsworth to be a friend, someone who would talk with them for hours. It also wasn’t unusual for Ellsworth to show up at local shows, to hear guitarists play the instruments he made for them.

“He always had a way of making me feel good when I’d see him, but that was Lynn. That’s how he was,” said his friend Pat Barclay. “He never hesitated to let me know how strongly he admired the way I played – which was an honor coming from him.”

Before they met about five years ago at a show, Barclay knew who Ellsworth was. He knew him as a premiere maker of the Fender Stratocaster-type electric guitar and the cofounder of the renowned company Boogie Bodies Guitars.

Ellsworth teamed up with another luthier pioneer, Wayne Charvel, to create the company in 1976. Ellsworth specialized in making guitar bodies from his shop in Puyallup and shipped them to Charvel to finish.

At the time, other companies were ramping up mass production of lower quality guitars, which led to the rise of Boogie Bodies as one of the first companies to offer replacement parts.

This led to “hot-rodding,” which is when a guitarist replaces stock parts of their instrument with nicer pieces to make it more powerful and attractive. Though it earned widespread recognition, the company fizzled around 1980.

But Ellsworth continued making custom guitars. As many luthiers do, he would attend shows to try to get his creations noticed by worthy guitarists.

"I met Lynn at a show, and he came up and noticed I was a left-handed upside-down guitarist,” Barclay said.

This refers to left-handed musicians who play a guitar made for right-handers, but flip the instrument over to play with their dominant hand.

“He decided I needed a guitar from him. And I thought that was very generous,” he said.

Their relationship grew fast. Either at live shows, belly up at a bar or spending time with Barclay’s clients as a community access specialist, the two connected by sharing stories from their younger years.

Barclay would share interesting anecdotes about his days of touring with B.B. King, Martha and the Vandellas, and Boz Skaggs. And Ellsworth would share about his relationship with some of rock ’n’ roll’s greats.

“He always had a good story,” Barclay said. “I mean, he was personal with these guys because they really enjoyed what he did when he built their guitars for them.”

It impressed Barclay that despite his health declining from a long struggle with diabetes, Ellsworth made it to many local shows in his later years. More impressively, Barclay said Ellsworth never eased up from what he cherished most about his relationship with his dear friend: their degrading, yet loving, banter.

“We are always giving each other trouble,” he said. “My most fun with Lynn was targeting each other back and forth like that because we were good at it.”

Another Spokane guitarist, Cary Fly, shared this appreciation of Ellsworth. He said calling each other profanities was endearing. It was somewhat of a “secret language,” he said.

“That meant I love you. That’s how we was: a gruff, grumpy guy,” Fly said. “But right underneath that was the biggest aquifer of love and tenderness and empathy – like an M&M.

“We would say those weird words and make people who overheard us think we hated each other,” he said. “But no. We loved each other.”

Ellsworth first introduced himself to the blues musician and vocalist at a venue in Seattle.

“He brought me two guitars, one of which was made out of a toilet seat,” he said, as he shared a long-lasting chuckle. “He was groovy.”

That was in 1971. He would bring two guitars for Fly to test out at most of his shows for the next few years until one impressed him so much, he played his whole set with it.

He started doing real good guitars, and then of course he started Boogie Bodies shortly thereafter,” Fly said.

It was Ellsworth’s ability to make high-quality parts for guitarists that led to the creation of one of the most famous guitars on the planet, Van Halen’s beloved Frankenstein of a guitar made of parts from different guitars – like a musical version of the fictional creature.

“It’s the most famous rock ’n’ roll guitar ever,” Fly said. “And those Boogie Bodies were the real thing too. If you have one of those today, their worth a lot of money because they are really, really nice.”

Fly said the creations were way ahead of their time because of their incredible finishes and pickups, or the mechanism that captures vibrations produced by instruments.

In addition to being behind some of the best guitars on the market, Ellsworth was also known as the inventor of the 2TEK Bridge, which isolates each string, allowing them to independently ring, thus enhancing the clarity of every note.

Some of his lesser-known creations were the Guinness Book of World Record’s largest guitar in 1980, a line of ultralight electric guitars cut from wood of burnt decks from homes damaged in a fire near Lake Pend Oreille, and collectors’ guitars made from wood of a barn and boat dock called the Barncaster. Only 12 were made.

Though he earned fame and recognition, Ellsworth never acquired great wealth. He wasn’t very concerned with earning profit, according to his later business partner of Lynn Ellsworth Guitars, Patrick Coleman.

“He was innovative and likable and a pioneer of the profession – just not the greatest businessman,” he said. “He used to say, “You know what $2 and fame buys you? A cup of coffee.” His wife, Diane Ellsworth, agreed.

“He just really enjoyed making them and giving them away, practically,” she said. “He had to sell some to buy more wood.”

Decades ago, Ellsworth would often travel to the Lilac City for his career as a medical sales rep. Eventually, he fell in love with the town and made the move where he met his wife.

Diane Ellsworth said he was impressed with the talented guitarists in town and loved hearing them play his guitars.

“He would just sit there and stare like they were his babies,” she said. “When somebody would buy one and it wouldn’t come home, it was sad. That was really hard for him.”

Through sniffles and giggles, Ellsworth remembered the many eccentricities of her late husband. She recalled how he would pay for wood with a wad of $2 bills, drive around town in a Cadillac hearse and persistently play loud music in their Millwood home.

“He was hard of hearing from all those years backstage,” she said, laughing. “But he loved music, so our house would always just be shaking with Billy Idol or, my gosh, ‘Stranglehold’ by Ted Nugent.”

During her 16 years with Lynn Ellsworth, she said she has probably acquired more guitar-tech knowhow than most guitarists – a notion that made her laugh and cry simultaneously.

And she wasn’t the only one. Today, Blake Ellsworth is carrying on the legacy of his father.

Dianne Ellsworth recalled a time when he attended a meeting with her, his father and a few dozen local blues players where he brought a hot-rod red Stratocaster.

“Even now, I have goosebumps thinking about the way that guitar sounded,” she said. “Everybody in the audience looked at Lynn and I, and we just kind of nodded our heads.”

Lynn Ellsworth, who specialized in turning a hunk of wood into a beautiful body, often mentioned how proud he was that his son, who mastered the skill of hot-rodding with the parts his dad carved, made better guitars than him, she said.

Blake Ellsworth manufactures and sells instruments under his company name, Bad Azz Guitars, using the methods he learned first-hand from growing up in his father’s sawdust-coated guitar shop.

“It’s important for me, especially now that he’s passed to, you know, continue to carry on the family name in guitar building,” he said.

In addition to his luthier techniques, Blake Ellsworth also inherited his father’s unwavering work ethic, appreciation of a good joke and the gratification only felt by a true craftsman.

“He would take raw wood and route it, shape it, sand it and finish it until it became a beautiful, playable instrument – started from nothing,” he said. “But what he enjoyed most was watching people’s reaction and the happiness that they get from playing his instrument.”

“And now I enjoy it too.”

Lynn Ellsworth is survived by his wife; his sons, Phil and Blake Ellsworth; his daughter, Amie Kasarda; and nine grandchildren. He was preceded in death by his daughter, Heidi Ellsworth.