Road geeks get their kicks on Route 66, or even on I-90

Erick Johnson knows why that road sign in Ellensburg belongs in Kentucky. And why a mileage sign leading into Ritzville is made of wood, and a highway shield for U.S. 99 does not belong in Seattle.

Johnson is a road geek, a person for whom highways rise from mere utilitarian pavement to the realm of art.

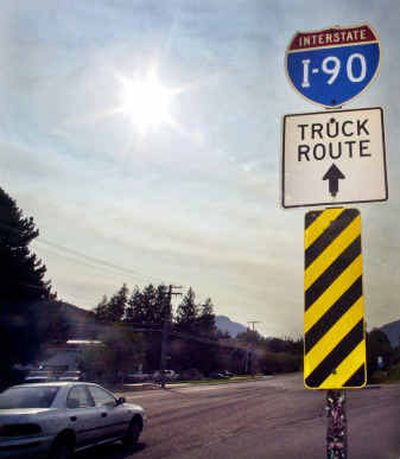

“I’ve always been interested in places and the movement of people,” Johnson, of Palmer, Alaska, said. His favorite highway is Interstate 90 in Washington, and he explores “the central role that I-90 plays in the commerce and the people in the state of Washington. It’s the only thing besides the Columbia that ties east and west together.”

On his Web site, he deconstructs the entire history of the freeway, detailing changes in river crossings, mountain pass approaches and rest area signs.

Highway enthusiasts, some who call themselves “road geeks,” know when a road sign is incorrect. They can describe, turn-by-turn, where old state highways snaked through towns. They know how many bridges cross the entire route of the Columbia River.

Some think it a travesty that Interstate 99 in Pennsylvania is west of Interstate 81, because north-south freeways are supposed to be given odd numbers in order from Interstate 5 on the Pacific Coast to Interstate 95 on the Eastern Seaboard.

Many road geeks get their fix on the Internet.

Johnson’s site, like many others, contains pictures of “sign goofs,” like the onramp to State Route 99 that has a U.S. Highway 99 sign on it. And the sign outside of Ellensburg is round, a style of sign designating state highways in Kentucky, but not Washington. And the wood sign in Ritzville? It’s a rare piece of history from the old highway that crossed Washington, U.S. Highway 10.

Johnson has traced the old path of U.S. 10, which was replaced by I-90. He feels for the historic highways and small towns that were bypassed and marginalized by the Interstate system.

“The older roads went through places that were more quirky and interesting,” Johnson said. “You had more of an opportunity to take in the sights.”

Historic preservation of old highways is a common theme among road geeks.

Two highways in Florida that were decommissioned and absorbed by U.S. Highway 41 between 1950 and 1951 might be forgotten if not for Robert V. Droz.

He has their old routes catalogued on his Web site, with each turn in the road carefully detailed. He had friends in the Florida Department of Transportation make up replica signs from the routes to hang in the office where he works as a roadway designer for Volkert & Associates in Tampa.

Droz keeps a record of every federal highway that was proposed but not built, as well as all of the highways that were constructed.

Mark Bozanich, a cartographer for the Washington state Department of Transportation, keeps a Web site detailing all of the highways in Washington.

One section features photos of every bridge that crosses the Columbia and Snake rivers. Bozanich collected the photos on trips throughout the region.

Bozanich’s site draws visitors who are looking for information about a specific highway in the state, or who wonder what an old road’s number was.

“One can go through a bunch of legal documents, but that would be more time-consuming than going through it the way I have laid it out,” he said.

Most road geeks found their love for highways when they were children driving around America on the complex web of roads, many built from 1927 to 1950.

The sophisticated numbering codes and interconnectedness of the system caused Alex Nitzman of San Diego to love roads. He operates one of the most detailed Web sites.

For example, he has a page devoted to Interstate highway signs, known among asphalt aficionados as “shields.” It contains photos of a sign from every interstate in every state in the nation.

Nitzman also explains all the differences in the signs since 1958. A series of photos, labeled and organized by year, shows minute variations from one decade to the next.

For a long time, Nitzman thought he was alone in his passion. But when the Internet came around, he found Andy Field. They combined their knowledge and together took road trips to various locations, videotaping highways and shooting photos of signs and interchanges.

Their work turned into a comprehensive guide to the Interstate Highway System.

Road geeks get together in restaurants for occasional meetings, often at sites close to a particular piece of highway construction, but Nitzman said the conversation isn’t always about roads.

“We only talk about roads 25 percent of the time,” Nitzman said.