Encounters

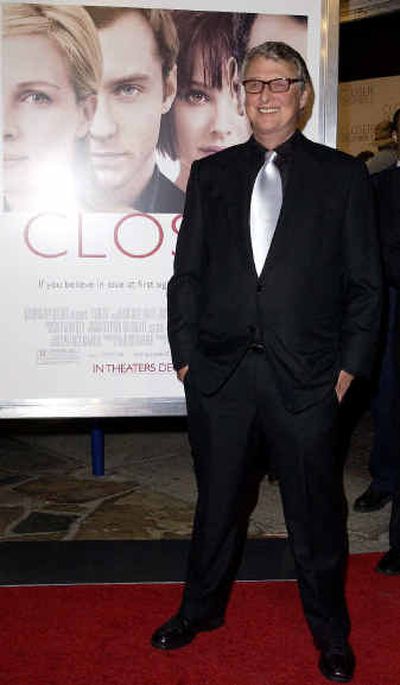

In “Closer,” Mike Nichols’ film version of the acclaimed, acidic play dissecting sexual politics, men are once again speared and splayed.

So does Nichols, who carried out similar assaults on the male ego in 1971’s “Carnal Knowledge” and in 1994’s “Wolf,” ever feel like a traitor to his gender?

“Oh my God, I feel honored someone would think so,” he says, laughing. “Any contribution I might make that would help civilization move forward a bit, I’m ready to fall on the sword.

“But I never really thought of this as any kind of attack or apology. What disturbs people, I think, is the honesty. … Do you really live somewhere these words and ideas are never addressed? Where is that place?”

Good question. Playwright Patrick Marber says “Closer” – in which two couples come together, come apart, then come together again in different formations – was rooted in personal experience, both his own and that of his friends.

The film version, which opens Friday, stars Jude Law as Dan, a newspaper obituary writer who takes a stranger, played by Natalie Portman, to a hospital emergency room after she has been hit by a cab at a busy London intersection. All is well until the novel Dan has been working on is published and his book jacket photo is taken by a photographer played by Julia Roberts, with whom he is instantly smitten.

But then a practical joke leads to Roberts’ character meeting a dermatologist played by Clive Owen, and things are subsequently tangled in ways that would be unfair to reveal here. It’s best to say that “Closer” is a searing and confrontational look at modern love and sex that will cut close to more than a few bones.

“I read the play before I saw it performed, in 1999, I think,” says Nichols, “and recognized pretty quickly it was something I might be suited for. But I understood that Patrick, who had directed it himself in London and on Broadway, wanted to direct the movie, so I reluctantly dropped the idea and moved on to something else.”

Eventually the two would collaborate, with Marber writing a screenplay that made some substantial adjustments. The women in the play, originally English like the men, are now American. And the formerly melancholy ending is now something like uplifting, or at least hopeful.

But there still are plenty of powerful moments, including a critical scene in which Owen, under the impression he is corresponding via the Internet with a woman (it is actually Law), engages in dialogue so dirty it might scorch Eminem’s ears.

“I was disturbed when I read it, but not shocked,” says the 73-year-old Nichols. “It’s hard for me to imagine that there is anyone who hasn’t heard these words, unless they are born-again Christians who are forced to make an enormous effort to disconnect from what’s being said and done in this society. That’s not to stereotype anyone – only to say this sort of thing is pervasive. You turn on your computer, and it’s there.”

Still, he says, “I have no doubt this movie will make a lot of people uncomfortable. But I also believe it has the capability to make men and women start talking to each other in ways they haven’t, and that can only be good.

“I was remembering the other day something about when Elaine (May, one half of the pioneering comedy team Nichols and May) and I first hooked up and started writing together, and how Elaine, being the person she is, would regularly say something to me that made me reconsider everything I thought was true about the world and relationships.

“I’d say, ‘Is this how women actually think?’ And Elaine would say, ‘Of course, do you never listen?’ I know I tried to after that.”