Point of dispute

Presidential hopeful John Kerry and other U.S. politicians who support abortion rights aren’t the only Roman Catholics to face possible exclusion from Holy Communion.

Every day, divorced Catholics who’ve remarried without first securing a church annulment are banned from receiving the sacrament.

Gay rights supporters wearing rainbow-colored sashes also have been turned away by bishops who don’t want the sacrament used for political statements.

And six years ago, John Prenger was notified that he, too, was being barred. He’d left the priesthood to marry after 20 years of service in the Diocese of Jefferson City, Mo.

But the politicians argue their case is different because they haven’t directly violated church law, according to Kenneth Pennington, a church law historian at the Catholic University of America in Washington.

“A few bishops are trying to selectively bar Catholic politicians from Communion for upholding the law of the land,” he said. “This is a new idea among the bishops.”

However, the wrangle with Catholic politicians over abortion is old. It has taken center stage because of Kerry’s bid to become only the second Catholic in history to be elected president.

Sixty-six percent of Catholics say they don’t want bishops pressuring lawmakers and that it won’t affect their vote in November, according to a poll released recently by the Quinnipiac University Polling Institute in Hamden, Conn.

Most of the bishops who lead the nation’s 195 dioceses haven’t taken a public stance. Some say they are awaiting the results of a bishops’ task force that’s drawing up guidelines on how to relate to those in public office.

(Bishop William Skylstad of the Diocese of Spokane hasn’t made any public statements on the issue. He said he is working on a statement and he plans to release it next week.)

Kerry’s archbishop, Sean O’Malley of Boston, has put the onus on the politicians not to receive Communion.

But two of the U.S. church’s highest-ranking officials – the cardinals of Los Angeles and Washington, D.C. – said they would not withhold the sacrament.

Denying Communion cuts Catholics off from what many consider their most intimate encounter with Christ.

“It’s death dealing,” said the Rev. Prenger of Columbia, Mo., who left the church to become a Charismatic Episcopal priest after being barred from the table. “It’s as if the bishop told me to shoot myself in the head spiritually.”

Holy Communion is so central to Catholic spirituality that it’s the focal point of every Mass. Catholics believe they’re receiving the body and blood of Jesus, not mere bread and wine.

“Eucharist is the highest sign of our unity with each other as a faith community,” said the Rev. Stephen Bierschenk, pastor of St. Michael the Archangel Catholic Church in McKinney. “You do not need to be sin-free, but you need to be free of serious sin.”

Church officials, however, have long debated what constitutes serious sin.

Priests who leave their ministry and undergo a process known as “laicization” – return to the lay state – can receive the sacraments. But those who leave and marry without undergoing the process are technically ineligible for Communion.

“Most of those priests continue to receive the Eucharist without any problems,” said Terry Dosh of Minneapolis, former leader of Corpus, a national organization of resigned priests who’ve married. “Most priests aren’t going to deny them Communion.”

Irene Varley, who leads the North American Conference of Separated and Divorced Catholics, said Catholics who remarry without an annulment tend to be of two minds on being restricted from Communion.

“There are those who truly, truly want to follow the letter of the law, even if it means not taking Communion,” she said. “And there are those who think the rules are unfair and follow their conscience. Some priests deny them Communion, but many don’t.”

Historically, the church has put the burden on Catholics to decide whether they were worthy to receive, except in extreme cases.

Some church leaders say it’s an embarrassment to have Catholics supporting abortion legislation when it goes against fundamental church teaching.

“These politicians are making a mockery of the Catholic faith,” said Amarillo Bishop John Yanta. “A lot of these politicians feel like if you go to church, you’re a good Catholic.

“But actions speak, too. They should not come forward for Holy Communion.”

At least two bishops advocate carrying the sanctions beyond the politicians. Bishop Michael Sheridan of Colorado Springs has said the Catholics who voted them into office shouldn’t receive Communion either – at least until they’ve repented.

And Dallas Bishop Charles Grahmann argues that CEOs of media corporations that support abortion rights, anti-immigration policies, the death penalty and gay marriage should also refrain from Communion.

“These individual CEOs are as much of a threat to society as politicians who vote for abortion,” he wrote in a column for the diocesan newspaper. “Neither should present him/herself for Communion.”

That kind of sacramental censuring is foreign to many Protestants.

“We would not keep someone from coming to Communion because of a public stance they take,” said Bishop Kevin Kanouse of the Northern Texas-Northern Louisiana Synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America.

“It’s God’s gift that is given,” he said. “If it counted on anyone being right and perfect and acceptable, then none of us could take Communion.”

Many Protestants practice “open” Communion, meaning baptized Christians of any denomination can partake. Pastors do not act as a liturgical police but rely on an honor system to ensure that those who come forward are eligible.

“The presumption is that those who commune are communing in faith,” said Ronald Byars, a theologian at Union Theological Seminary in Richmond, Va. “Eucharist is not a reward for the worthy, but there for sinners aware of their need for God’s grace.”

Catholics and Orthodox Christians practice “closed” Communion, meaning the sacrament is only for baptized members of those faith communities.

“It’s simply saying that those who partake of the cup are of one faith,” said Peter Bouteneff, a theologian at St. Vladimir’s Orthodox Theological Seminary in Crestwood, N.Y.

President Clinton, a Baptist, drew criticism from Catholics when he took Communion from a priest while visiting South Africa in 1998. But many priests say it’s likely that they’ve inadvertently given Communion to worshippers who weren’t eligible.

As a practical matter, priests say it’s impossible to know the individual state of the thousands of souls coming forward for the sacrament on any given weekend.

“I never deny anyone Communion on principle,” said the Rev. R. James Balint, pastor of Prince of Peace Catholic Church in Plano, Texas. “I don’t ask for identification.

“I presume everyone is there in good faith. Some may not be, but it would be difficult for me to judge.”

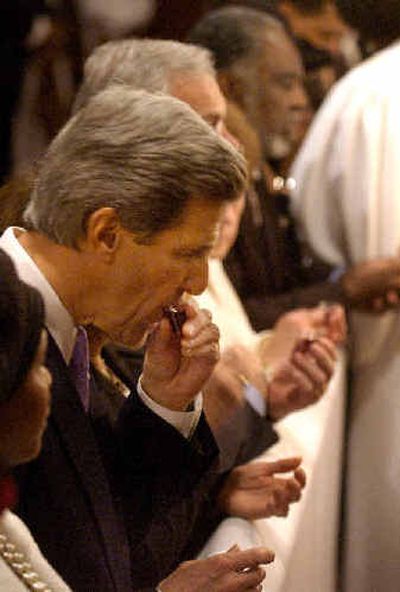

Meanwhile, Kerry continues to receive the sacrament. And recently, 48 of his Catholics colleagues in Congress, all Democrats, sent a letter to church officials protesting attempts to bar them from Communion.

“We do not believe it is our role to legislate the teachings of the Catholic Church,” the letter said. “Because we represent all of our constituents, we must, at times, separate our public actions from our personal beliefs.”