Explore national park lodges’ great indoors

T

HIS ISN’T A LOBBY — it’s a nave. That sweet scent isn’t just cedar carried in on a mountain breeze — it’s a whiff of ritual incense. The voices, muffled by the towering space, are as much the murmur of a congregation as the chatter of holiday makers.

In short, this isn’t tourism — it’s high church. And the country’s great national park lodges are not just — they are America’s summer cathedrals.

This one happens to be the Glacier Park Lodge, on the eastern edge of Montana’s Glacier National Park. But the arrival ceremony, which I never tire of observing from a comfortable mission armchair in the lobby, is just a variation of the one at Old Faithful Inn in Yellowstone, the Ahwahnee in Yosemite or any of their grand sisters holding court in the mountains, deserts and canyons of the American West.

In Glacier, it goes like this: Newcomers enter the lobby, still distracted by the demands of their journey. Inevitably, they check their strides, raise their faces in wonder at the great hall created by 24 Douglas fir trunks — tall as steeples, bigger around than a man’s hug — and seem very near to crossing themselves in the shadow of this soaring indoor forest.

Lots of lobbies wow. But here, eyes lift and jaws fall with something more than mere approval. This is what churches attempt to instill, a simultaneous sense of awe and comfort. The awe comes from the titanic scale of this timber-frame palace, hand-wrought from colossal parts in a pre-mechanical age. In just that one immense log over the foyer there must be enough lumber to build a bungalow.

And it’s easy to imagine the men swarming among the bones of the roof back in 1913, wrangling up the massive trusses with blocks and tackle and muscle and mules. You don’t build a structure like this — you just tame its wild parts long enough to lash it all together and jump back until she’s broke good and proper. They built it mostly over one stiff Northern Rockies winter.

The comfort, meanwhile, comes right from the wood, that most welcoming of materials. This same space made of marble would dazzle, but it wouldn’t delight, it wouldn’t invite. But the warm, fragrant, once-living skin of hewn beams and plank flooring and log columns welcomes us in from the wilds, not just for protection but for a snuggle. No one snuggles with marble. You don’t curl up in front of a limestone fire.

In Glacier Park Lodge, folks gather around the lobby like picnickers in an old-growth grove. In that nether-hour between the day hikes and the evening meal, groups and families sprawl over the armchairs amid a litter of hot chocolate cups and PowerBar wrappers. A dappled light from distant skylights filters down on a couple of college-age Asian girls writing postcards on the opposite arms of a mission couch. A toddler shuttles between the taxidermied mountain goat in the glass case and one of the enormous tree-trunk columns. Every time he reaches the tree, he hugs it lavishly, wrapping his arms to their tiny extremes and placing his cheek against the bark. At the base of the 48-foot fir trunk, he looks like a little blond beetle.

In a lodge, the lobby is the living room. The guest rooms are almost an afterthought. With some showy exceptions (some of the oldest rooms in the Old Faithful Inn, for example), guest chambers tend to be austere, plainly furnished bunk rooms. (Some of them are frankly homely, particularly in the many later-decade additions and wings that have been slapped on to meet an ever-growing demand). In Glacier, as at many others, the rooms don’t have televisions.

Lodges are not luxury hotels by and large; because they sit amid the continent’s most spectacular scenery, they don’t have to be. After a 10-mile trail ride, it’s the hot shower that matters, not the milled soap or the thick towel. Who pines for pay-per-view in a room where every window frames an Albert Bierstadt canvas or an Ansel Adams print?

The result is a uniquely communal tradition of lodge guests spending their free time together. Public spaces are designed for constant use. Scrabble players and puzzle makers share the long coffee tables. Around the cavernous stone fireplace, people fill a haphazard amphitheater of seats, sitting and staring as if the flames themselves were telling old tales of wild lands and wild men. Writing tables and card tables are tucked into every crevice. In the window-lined breezeway, backed by a misty view of the Rockies, two older couples play gin rummy with silent efficiency. “You stinker,” cries a white-haired man amid sudden laughter. They count their points and one of the women marks the score in a battered spiral notebook that suggests this is a vacation ritual.

“We have people who come year after year,” says Michael Buck, a volunteer tour guide from St. Paul, Minn., who has been spending summers at Glacier since 1960. “They treat it like it’s their home.”

Buck is a trim retiree in a white dress shirt and a Glacier Park ball cap. His main job is driving lodge guests around in a “jammer,” one of the park’s vintage red sightseeing buses with roll-back canvas tops. Much of the old fleet, long beloved for open-top drives on the spectacular and nail-biting Going-to-the-Sun Road, was recently restored and returned to service. Similarly, several of the 1920s-era touring boats are still at work on Glacier’s mountain-rimmed lakes. This is a park with a keen fondness for its old days.

Buck describes the experience of early-20th-century visitors, mostly middle-class tourists who could have been expected to spend their holidays in Europe. But after Louis Hill, the ambitious president of the Great Northern Railway, built this lodge, he successfully filled his trains with Glacier-bound passengers by beseeching them to “See America First.” When they arrived, they were greeted at the station by traditionally dressed Indians from the adjacent Blackfeet reservations and driven in wagons the short distance to the lodge.

“He wants the place to really impress them,” Buck says. “They’ve been on the train for at least two days, crossing nothing but grasslands at a speed of 45 miles an hour. Then they pull up to this.” He gestures at the looming facade, rising like a mountain ridge off the plain. “The Blackfeet were the waiters and the entertainment, and some nights the drumming ceremonies would go on all night right here in front of the hotel.”

Years later, the red jammer buses replaced the wagons and more lodges and chalets were built around the park.

“The idea that they’ve been able to preserve this building in this kind of condition is just dramatic,” Buck says. “The only thing really new about it is the sprinkler system.”

Well, there are credit card machines in the gift shop and Sweet ‘N Low in the dining room and a few other nods to modernity. But that sprinkler system is undoubtedly the most important update in a hotel that is essentially a stack of one-match kindling sitting in a wildfire zone.

Fire! It’s hard to imagine a more prestigious and loved group of buildings that are more chronically imperiled than the great wooden lodges. As firestorms return to the West each year like wilderness hurricane seasons, these stolid buildings begin to seem more like sand castles than stockades. At the end of some future summer, it’s entirely possible that one of these lodges will not be standing.

Glacier has had its close calls. During last summer’s fires, 136,000 acres of the park burned. And one of the park’s other post-and-beam wedding cakes, the exquisite Lake McDonald Lodge, was evacuated and remained swathed in threatening smoke for weeks. Lake McDonald, on the park’s west side, is a smaller resort, a lakefront hotel with alpine trim that opened in 1914. Its lobby, surrounding a grand walk-in fireplace, is lined with log rail balconies and crowded with watchful moose, elk, mountain goats and other wildlife trophies. It’s a special room, and its loss would break every tourist’s heart that ever beat within its walls.

But within recent memory, Yellowstone’s venerable Old Faithful Inn, said to be the largest log building in the world, came nearest to a bonfire finale. The voracious flames of the 1988 fires that blackened more than a third of Yellowstone licked at the lodge’s very eaves. This eminent American icon was spared only by a new external sprinkler system, a tiny providential shift of the wind and the heroics of firefighters and bellmen chasing embers off the roof — steeply pitched against a blizzard but helpless against a spark.

The dining room and lobby of the Old Faithful Inn — with its lodgepole pine pillars, burled log railings, split trunk staircases, lava rock chimneys and wrought-iron fixtures — are nearly the rival of the splendors outside its doors. The inn celebrates its 100th birthday this year.

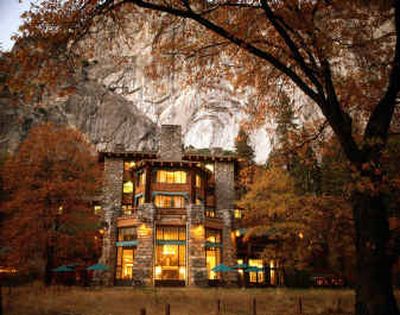

Our summer visits to national park lodges are pilgrimages to a younger, wilder America, and we want them not just in the wilderness, but of it. The Grand Canyon’s long and low El Tovar lines the southern lip of the canyon like another strata of geology. In Yosemite, the blocky granite face of the Ahwahnee tucks into the base of the high gray cliffs like an outcropping, not an add-on. Oregon’s Crater Lake Lodge, opened in 1915 and recently completely restored, fits snugly into the rim of rock that forms the walls of the deep, dramatic lake.

It’s not that these great lodges are camouflaged. In fact, they brim with personality and, once seeing them, none of them wears a face you’re ever likely to forget. But still, each manages in its own way to be of a piece — and at peace — with its feral landscape.

And, like a chapel in the wild, that’s what a national park lodge offers us: a small place in a vast space where we might find peace, with nature.