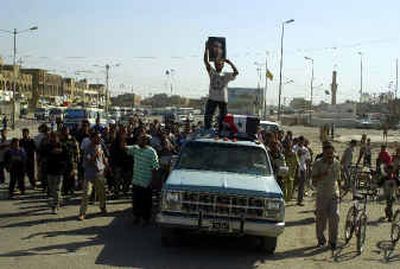

Fighting persists in Sadr City

BAGHDAD, Iraq – Standing on a street lined with shuttered stores, Karim Habib watched four U.S. tanks rumble through the impoverished Shiite enclave of Sadr City, past what was left of a police station blown up a few days earlier.

Once grateful to Americans for ridding them of Saddam Hussein, many in this Baghdad slum have come to hate U.S. troops for bringing chaos – and not much else – to their door.

“It’s like these tanks are rolling over my own body,” Habib said bitterly. “I don’t care if the fighting hurts our businesses as long as we don’t see them (the Americans) in our country.”

It seems like the fighting never stops in Sadr City, where insurgents pop out from behind crumbling walls to fire rocket-propelled grenades at U.S. tanks, raid police stations where U.S. forces are deployed and set roadside bombs timed to explode when American convoys pass.

“Sadr City is the heart of darkness, and to control it is very, very difficult,” said Amatzia Baram, an expert on Iraq at the U.S. Institute for Peace in Washington. “These guys want to fight.”

Beaten down by poverty and a dearth of opportunity, many here are growing impatient with an occupier they say has promised much and delivered little. The slum’s back alleys have become fertile recruiting grounds for fighters loyal to the radical cleric Muqtada al-Sadr, whose fiery rhetoric capitalizes on fears that a non-Muslim occupier is defiling holy lands, torturing men and violating the privacy of women.

Battling the occupation gives the downtrodden and unemployed youth a cause to rally around, Baram said.

“Their social status is below zero, and all of a sudden, they are elevated to the level of jihad warriors. … It gives them power,” Baram said. “This is intoxicating.”

The district of 2 million people was long oppressed by Saddam, whose Sunni-dominated regime crushed any sign of Shiite dissent. Once Saddam was gone, al Sadr’s movement stepped into the power vacuum, drawing trust and loyalty by providing free medical care, restoring power and fixing telephone services.

His family credentials – Sadr City is named after his father, a senior cleric killed by suspected Saddam agents in 1999 – helped win his following.

Apparently underestimating al-Sadr’s appeal, the U.S.-led occupation authority closed his newspaper, arrested a key aide and announced a warrant for his arrest in the April 2003 murder of a moderate cleric. Outraged loyalists rallied to his defense and then kept on fighting, motivated by religious zeal and admiration because al-Sadr stood up to the Americans.

“He’s like a military leader,” Habib said. “If he said: ‘I want the people to rise,’ they rise.”

Habib, who manufactures soft drinks, said the Americans asked for trouble by making false promises and then attacking the people who were making good on efforts to alleviate poverty.

“They are the ones who made the people fight them,” he said of the Americans. “They said they would rebuild the country and give the people their rights. It’s all lies.”

U.S. military officials argue their presence is needed to keep the militia from controlling the neighborhood. They say their military actions are usually coupled with reconstruction projects and that they would have focused more on rebuilding if they didn’t have to pursue attackers.

Their explanations find little resonance in Sadr City, where residents angrily swap stories – true or not – of the latest U.S. atrocity: Troops snatched young men at night; they shot a mentally retarded boy who aimed a fake gun; they randomly opened fire, scaring children.

In private, some people express anger at the Shiite militiamen, saying some of them are criminals with nothing better to do. Few would dare criticize the fighters in public, though, for fear of reprisal.

Al-Sadr aides argue that saboteurs stage some attacks, such as blowing up the al-Karama police station, to create strife and tarnish the militia’s image.

Previous cease-fire agreements in Sadr City have collapsed with each side blaming the other.

Yet while Sadr City has proven to be a tough front in al-Sadr’s battle with the Americans, it seems to get relatively little attention within the larger Shiite community.

In the southern holy cities of Najaf and Karbala, for instance, top clerics rallied to stop the violence to protect Shiite Islam’s most sacred shrines. That kind of pressure has not been applied in Sadr City, where not much is of consequence – except to those who live here.

Pieces of trash float in pools of greenish sewage water. Sheep and horses pick at mounds of rubble. Electricity outages force families to bake in the sweltering heat.

Clashes between U.S. troops and al-Sadr’s fighters have left Sadr City with shattered storefronts, bullet-riddled squat buildings and black banners mourning “martyrs.”

Fatma Hussein says she isn’t sure whom to blame – the Americans or the Shiite militia – but she knows she wants the violence to end.

“What fault is this of ours? Our children are scared,” she said. “We are hurting.”