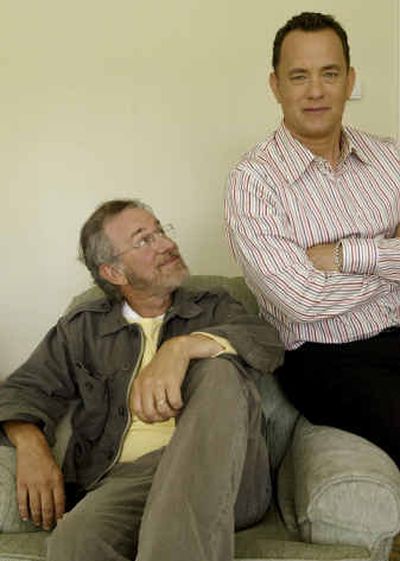

Bond of brothers

Tom Hanks had this problem. Feeling incredibly grateful that Steven Spielberg had given him a chance to do the sort of part he never imagined getting, he spent the weekend following the first days of shooting “Saving Private Ryan” dreading a confrontation he knew was coming.

“This movie was really a big deal for me,” says Hanks. “I had been pinching myself because I couldn’t believe I was doing it.

“And then we start working, and I see that the 2 1/2 pages of dialogue I had to shoot for the next scene were just bad, idiotic. And I knew I was going to have to talk to Steven about it, and because we were friends before we were collaborators, it was a lot harder than it would be usually with a director.

“So I get to the set, and I’m in the hair and makeup trailer fretting about this, and Steven comes in and says: ‘Tom, that dialogue in the next scene is just unfixable so I’m just going to take it out. I’ll cover the thing visually.’ And it was at that moment I thought, ‘You know, this thing really could work out.’ “

Now the collaboration that began with “Saving Private Ryan” continues with “The Terminal,” the third feature film starring Hanks and directed by Spielberg.

“The Terminal” was loosely inspired by the true story of an Iranian refugee who has been living in Charles de Gaulle International Airport in France since 1988, having arrived there with no passport. (He has since proved his political refugee status, but chooses to remain in the airport.)

“We talk about various projects a lot, pass things to each other,” says Spielberg. “But we seem to know which ones will be right.”

He says “Catch Me If You Can,” the 2002 crime thriller co-starring Hanks and Leonardo DiCaprio, “we sort of knew from the start would be right.”

While Hanks got involved with “The Terminal” first, Spielberg says once he saw the final script, “I got excited enough to want to do it together.”

Hanks plays Viktor Navorski, a citizen of a fictional Balkan state called Krakozhia. At almost the exact moment Viktor is going through customs at an unidentified New York City airport, a military coup in his country renders his passport invalid.

That leaves him unable to enter the United States or to return home. Viktor’s situation is complicated by an ambitious customs official (Stanley Tucci) who does his best to be unhelpful.

“Obviously making this film post-9/11 posed a number of problems, and if someone had come to me with a script in which some poor immigrant had been chained to a pole at JFK, I wouldn’t have gone near it,” Spielberg says.

“The tone was everything in this, because we’re telling a simple story. But we’re hoping to make a point or two without being too obvious.”

To Spielberg, the point was the way the United States appears to be moving away from being the great melting pot toward “tribalization.”

“We’re going through this period of self-segregation, as the sociologists call it,” he says. “But if you ever have occasion to be in the international lounge of a metropolitan airport, you realize the circumstances don’t allow that. Everybody is doing the same thing. Waiting, worrying, wondering what’s going to happen next.”

As part of their research, Hanks and Spielberg spent a day with customs and immigration officials at Los Angeles International Airport, where they were taken to what is called “the secondary room.”

“It’s where people who have problems with their papers or status, or who have simply tried to innocently bring fruit or something prohibited in the country, go to wait and wait some more,” says Hanks. “These aren’t people suspected of being terrorists; they’re just people who don’t understand the rules or are caught in some bureaucratic snafu. Man, if you ever have an urge to see some really sad faces, that’s where you want to go.”

Neither Hanks nor Spielberg wanted to make a movie full of sad faces. Their “Terminal” is a place where an angry Indian immigrant (Kumar Pallana) or a sad stewardess from Nebraska (Catherine Zeta-Jones) can, with help from people very unlike them, rediscover the best parts of themselves.

It’s where a shy Mexican food service worker (Diego Luna) can find the courage to declare his affection for the suspicious African American immigration clerk (Zoe Saldana) who daily stamps “rejected” on an ever-hopeful Viktor’s visa application.

“It was more comedy than I’ve ever done before,” says Spielberg, “but we’ve been calling it serious comedy. I’m still uncomfortable with the idea of making a movie that’s nothing but jokes. But I’ve definitely been lightening up after ‘Ryan’ and ‘Schindler’s List,’ and that’s a conscious thing.

“I know I’ll return to serious material eventually, but I really like the idea of just entertaining audiences again. And, of course, Tom and I are on the same wavelength. We make movies together for the same reason we became pals, I think. We both came from broken homes, so we tend to put a high value on families and being with our families. The things that make him smile make me smile, and we have a lot of the same interests — and that gets reflected in the movies.”

Hanks, 47, and Spielberg, 57, got to know each other when Hanks starred in a comedy produced by Spielberg’s Amblin Entertainment called “The Money Pit.” They soon became what Hanks calls “barbecue buddies.”

But with Hanks establishing himself as a comedy star and Spielberg purposely moving away from fantasy to more serious dramatic fare, their professional lives remained separate — until, Spielberg says, “we took the leap of faith with ‘Ryan.’

“I didn’t want to jeopardize our friendship, but I also knew he was the only guy for that role,” Spielberg says. “He cared about it the same way I did.”

The first thing he learned about his old friend and new leading man, says the director, was to get out of his way.

“When Tom’s got his mojo working, I know enough to just point the camera and let him go,” Spielberg says. “You know his breakdown scene in ‘Ryan?’ One take, that was it. He was just right there.

“On the set, the guy has no ego or temperament, which is great because it means I don’t have to be walking on eggshells the way you do with some big-name actors I won’t name. It means I can relax, which is a blessing.”

“That’s only when I’m taking my meds,” jokes Hanks, adding: “What I’ve learned about Steven is that he’s absolutely unshakable in his convictions, which is not to say he won’t let you do 17 takes, but that he’ll always use the one he knows works best for the film. He lets you go exploring, but he doesn’t let you get lost.”

The way the two relate to each other is evident when the conversation turns to a major plot point in “The Terminal” that incorporates a famous photograph usually called a “A Great Day in Harlem.”

In it, more than 50 jazz giants are gathered in front of a Harlem brownstone for a group portrait taken by Art Kane for Esquire magazine. One was composer-saxophonist Benny Golson, who wrote music for “The Terminal” and whom the young Spielberg first heard when he began hanging out with jazz-loving college friends.

“I spent a lot of time at the Lighthouse in Hermosa Beach and at (drummer) Shelley Manne’s Manne Hole back then,” says Spielberg. “Shelley and Benny worked on the soundtrack to ‘Jaws.’ “

“Oh, listen to him, Mr. Sophistication,” ribs Hanks, a self-described rock `n’ roll kid. “If it got beyond Miles Davis, I didn’t know about it. But, hey, I’ve spent a few years catching up. Someday I’ll be as cool as Steven.”