Movie Magic

The “Polar Express” screenplay describes an enchanted scene: A wide-eyed boy runs through the observation car of a 1950s locomotive steaming across the Arctic Circle to visit Santa Claus as two other children sing about Christmas cheer. What you see on a movie soundstage, though, is as removed from that image of holiday merriment as Hollywood is from the North Pole. Instead of a child dressed in pajamas, there’s Tom Hanks in a blue and black bodysuit so tight it should be worn only by Olympic athletes. In place of the gleaming train are a few pieces of set construction painted a drab gray, marking no more than a door here and a railing there. And where the script calls for brilliant starry skies, the background at this point is an enormous metal

grid holding 64 infrared receivers.

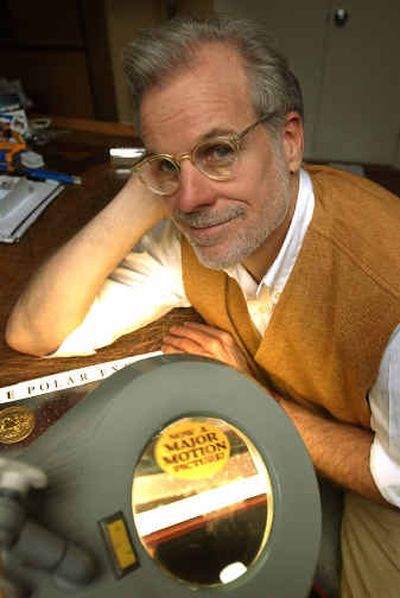

From his historical composites in “Forrest Gump” to his marriage of animation and live action in “Who Framed Roger Rabbit,” Robert Zemeckis repeatedly packs innovative tools into his movies.

But with “The Polar Express” – which opens in theaters Wednesday – the 52-year-old director may be taking his biggest leap yet, one which very well could create a new film genre somewhere between animation and live action.

Adapted from Chris Van Allsburg’s slim but richly illustrated children’s book of the same name, “The Polar Express” was made almost exclusively with a method called “performance capture,” which drops digitized human actors into a computer-animated world. The technique has been used in some video games and to a limited extent in earlier movies; Warner Bros. says “Polar Express” is the first feature made solely with the process.

While the mathematics of the process are beyond understanding, the mechanics are not.

Banks of fixed infrared receivers precisely record the body and facial movements of actors reading dialogue and performing scenes on an essentially blank stage. All of those recorded movements are dumped into computers, which are then used to create a digital character who can be outfitted with any costume, equipped with any prop and placed into any environment. (Animals in the film, from caribou to reindeer, were created by digital animators.)

To fashion a “Polar Express” character’s skiing atop a speeding train in a blizzard, Hanks mimes the action with 60 reflective balls on his bodysuit and 151 markers on his face. The infrared receivers record his moves, while the train, the skis and the digital snow are added after the fact.

It’s basically the same procedure director Peter Jackson employed in his “Lord of the Rings” movies to generate the character of Gollum, though the technique is far more refined. It is neither cheap nor easy; the sky-high “Polar Express” price tag and the creative gamble was so steep that Universal Pictures declined to make the film, even with Hanks attached.

While live-action studio movies can be filmed and edited in less than a year and cost on average $63.8 million, Zemeckis spent some 20 months making the $170-million “Polar Express.”

After a year and a half of post-production, he has a lot to show for all the time and money.

The Lycra-encased Hanks has been scaled down and transformed into a photo-realistic 8-year-old boy (Hanks plays five roles in the film), clothed in convincing pajamas. Where he and co-star Nona Gaye once ran through a mostly empty soundstage, they now have been placed inside an elaborately designed train rattling down the tracks. Twinkling galaxies and Northern lights illuminate the sky, as a snowy arctic wilderness fills the horizon. It’s simultaneously realistic and fantastic, reminding you of Van Allsburg’s oil pastel illustrations as well as such computer-animated movies as “Finding Nemo” and “Shrek.”

As with a computer-animated film, there’s technically no camera in a performance-capture movie. Thus, Zemeckis can navigate a three-dimensional world without minding the laws of nature. Indeed, his “Polar Express” lens flies out windows, over waterfalls, underneath hot chocolate carts, into keyholes, even up through the pages of a World Book encyclopedia.

When he took up Van Allsburg’s book three years ago after a false live-action start by director Rob Reiner, Zemeckis wrestled with how to adapt the story. The Caldecott Medal-winning book tells of a young boy’s train trek to the North Pole and the gift Santa gives him that restores the boy’s Christmas faith. It’s barely 1,000 words long. As spare as the book may be narratively, it is richly illustrated with 15 paintings inspired by the 19th century German artist Caspar David Friedrich. The challenge was how to expand the book’s story while preserving its distinctive look.

Zemeckis and screenwriter Bill Broyles set out to write a screenplay that would stick to the book’s beginning and end but cook up an entirely new middle about the train trip. Had he made the movie in live action, Zemeckis says, he would have had to “throw out all the glorious paintings.” Close readers of the book will recognize that each and every illustration is represented in the film.

Although Zemeckis briefly contemplated having Hanks play every “Polar Express” character, in the end he performed the roles of the lead boy, his father, the train’s conductor, a hobo and Santa Claus. Each of those is voiced by Hanks except for the boy, whose lines were read by child actor Daryl Sabara.

Hanks was able to do all five of his characters in just 38 days of principal photography, a fraction of what it would take in live action. Like the other “Polar Express” actors, he didn’t have to worry about hours of makeup, hitting his marks, or waiting for lights to be hung. He squeezed into his reflective suit, stepped onto a stage and acted, while the infrared receivers recorded every single thing he and his co-stars did. Hanks isn’t worried that performance capture will put actors out of work. If anything, he says, it could improve their lives.

“Any actor can now play any role,” he says. “Height doesn’t matter. Race doesn’t matter. Hair color doesn’t matter. Even gender doesn’t matter. If Meryl Streep can perform a great Abraham Lincoln, now she can do that in a movie.”

Like a movie-directing kid in a cinematic candy store, Zemeckis says it will be difficult to leave performance capture for live action.

Although he has not announced his next directing job, he is producing the thriller “Monster House,” which is being directed by Gil Kenan on a performance-capture stage.

“It’s going to be hard to go back,” Zemeckis says. “It’s so liberating not to deal with any physical restrictions.”