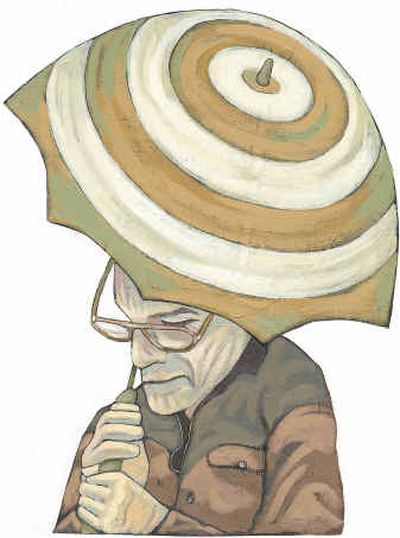

Age Gap

WASHINGTON — Bill Thomas is a rebel with a cause, a 44-year-old geriatrician who wants to overthrow an empire — the demographic empire of adulthood. That long season of life that has become like a cult, he says, a tyrannical power as vicious as the former Soviet Union, crushing dissidents by distorting childhood and marginalizing old age in a vain effort to control the world.

Say, what?

Adulthood is out of control, he explains in his latest book, “What Are Old People For?” (VanderWyk & Burnham). Adults have taken over the main continent of living, he argues, with their own set of rules and they have pushed out those who no longer fit in — the old folks — erasing millions in Stalin-like purges by sending them off to nursing homes and retirement communities, banishing them to a cultural no-fly zone of irrelevance.

He’s not kidding.

“Adults rule,” Thomas writes. “Their power is so complete, their control over our lives so encompassing.” What are nursing homes but a kind of Siberia for dissidents — elders who have been stripped of adult status? “Nursing homes function as instruments of adulthood, and they serve a purpose very similar to that of Stalin’s gulag archipelago,” he continues. “Under Stalin, the Soviet Union used the fear of the gulag archipelago to enforce Communist orthodoxy.”

In the same way, he suggests, the empire of adulthood uses the fear of nursing homes to enforce its ageist orthodoxy against growing old. Don’t ever let me go there, whisper frightened adults as they pass by their local long-term care facility.

Adult orthodoxy with its glorification of independence and focus on doing, getting and having, Thomas argues, is based on a false premise: “Adulthood pledges … an active life combined with eternal youth,” he writes. “In contemporary society, to act young is to be young. No limits are set on the means that may be employed in the pursuit of that illusion.” (Meanwhile, he points out, childhood, with its emphasis on test scores, academic achievement and organized sports, has lost its playful independence.)

Like the false orthodoxies that buoyed communism or slavery, the orthodoxy of adulthood needs to be challenged, he says, not just to liberate the oppressed (elders), but to free society from the grip of ageism.

“When (Abraham) Lincoln declared, ‘A house divided against itself cannot stand,’ he named the danger that slavery posed for the nation as a whole,” writes Thomas — just as the tyranny of adulthood now poses a danger for the nation as a whole. There is a “correlation between the liberation of elderhood and a general improvement in the well-being of all.”

All this hot-blooded revolutionary language! You might wonder: Is William H. Thomas, M.D., a little over the top?

I don’t think so. The redefinition of aging is a social revolution. Thomas is providing a language to awaken people — all of us in the thrall of adulthood — to the changes ahead in the life cycle. He takes on the role of the abolitionist as he challenges the fundamental orthodoxy of forever-young adulthood.

What about forever-old adulthood? That’s where the future lies, with the aging of populations around the world.

Thomas has walked it like he talks it. Long a champion of improving quality in nursing homes, in 1992 he started the Eden Alternative, a concept of care for the most frail and dependent, where the day revolves around close contact with plants, animals and children. Rather than an institution, the nursing home becomes a community. The Eden approach has spread to every state and to New Zealand, Australia, Europe and Asia.

After all, as Thomas explained in an interview, it was the elders in a nursing home who showed him how to break out of the cult of adulthood. He grew up in rural New York, taking for granted his extended family of older relatives. He aimed high in school, went to Harvard Medical School and set out to be an emergency room doctor. Along the way, he took a temporary job in a nursing home.

He never left. He listened to the people’s stories. They showed him how to transform losses into meaning; they offered the wisdom of being, rather than always doing. “What they set me free from was the idea that I could or should be the master of everything.”

They helped him transform his own losses into new life: the collapse of his first marriage led to renewal in a second marriage; the birth of two children with major developmental problems prompted a renewal of family life with all five children on a farm.

He saw the value in dependency and interlocking relationships between the strong and weak, the wise and the not-yet-wise.

Creating the Eden Alternative was the first step to honor elders and improve the lives of residents in nursing homes.

Challenging adulthood itself is the next step in creating an elder-friendly culture. Thomas sees new potential in forever-old; his mother became a minister at age 60. He sees the enduring value in growing old for all ages.

How does he answer his own question: “What are old people for?”

“They are the glue that holds the human community together. To deny old age is to invite anarchy in our lives,” he says.

Empires eventually crumble, Thomas points out. Numbers alone, with a swelling population of elders on the horizon, are destroying the empire of adulthood within.

“This century will be defined by our struggle over the questions related to aging and longevity,” he writes. “The liberation of elders and elderhood is not an aging issue. It is not a generational issue. It is not about government programs of public policy. It is not about aching knees, weakening eyes, or even the wrinkles that line our faces. It is a world-changing struggle that can remake the experience of life from cradle to grave. It is our last, best hope for saving our world from the all-conquering power of adults.”

Them’s fighting words.