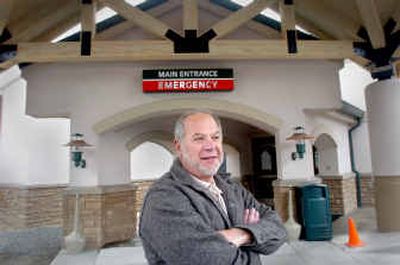

He got it done

KELLOGG – Vince Rinaldi doesn’t plan to land in the hospital any time soon, but Shoshone Medical Center is his choice for care, if the need arises.

“I’d go there in a heartbeat,” says the director of the Silver Valley Economic Development Corp. in Wallace. “It’s very good, a welcome change.”

The pleasantly pink Shoshone Medical Center in Kellogg represents new life for Silver Valley health care. Shoshone County nearly lost local hospital services a decade ago. The county’s two small hospitals fought to survive in a struggling economy further hobbled by a Superfund designation.

Shoshone Medical Center lived, but on life support until hospital trustee Jerry Cobb and CEO Gary Moore put it on the path to possible renewed health by finding the money to replace it with a new hospital.

For his efforts to save hospital service in Shoshone County, Cobb was chosen Trustee of the Year for 2005 in small hospitals by Modern Healthcare magazine. The business magazine circulates to 71,000 health care executives across the nation. It also awards a Trustee of the Year for large hospitals.

“It’s a really big deal,” says Steve Millard, director of the Idaho Hospital Association. “Jerry’s a very modest guy and won’t take credit for anything, but he should. He’s done so much for the community.”

Moore credits Cobb with the medical center’s $18.4 million transformation, and Cobb emphatically credits Moore. It took both men and help from many other people. But Cobb had experience and know-how that was hard to beat.

“He helped HUD (U.S. Housing and Urban Development) understand you could build on a Superfund site,” Moore says. “He made them comfortable with the fact that this is not a problem and they went ahead and agreed to do it.”

Shoshone Medical Center and a small hospital in Colorado asked HUD to guarantee commercial loans for them at the same time a few years ago. The two hospitals were the first. Major building programs were out of range for small hospitals because they had no way to repay loans.

For years, all hospitals received the same payments for medical procedures from Medicare. Large hospitals had enough demand for care from patients with insurance to help nourish their budgets. But most small hospitals didn’t have room for enough paying patients to bolster their budgets after Medicare’s meager payments. In 1997, Congress created a new designation – critical access hospitals – to save small hospitals from going broke and closing.

Now, Medicare reimburses critical access hospitals according to the costs of their work. Such hospitals have up to 25 beds, a 24-hour emergency room and are at least 35 miles from another hospital. Patients stay an average of four days. Twenty-six of Idaho’s 39 hospitals are critical access, including Shoshone Medical Center.

Payment changes helped SMC, but it needed more. Its building was nearly 50 years old and built for twice the population that lives in the county now. Remodels reflected a variety of decades. Replacing the building entirely was the answer. But Moore and most of his trustees doubted any institution would lend SMC enough money. Cobb believed otherwise.

Cobb has directed the Panhandle Health District’s Shoshone County operations since 1973. Since 1986, he’s helped his county learn to live on a Superfund site, an emotional process that’s buried him under as much criticism as praise.

“Life has to go on,” he says. “You can’t put a community on hold for 20 years.”

The cleanup removed 1 foot of lead-contaminated soil from the surface of the Superfund site’s accessible areas and replaced it with good dirt. Cobb and his staff developed a program that allows construction that disrupts the contaminated soil as long as the bad soil is returned to the ground and the barrier of good dirt is replaced. Contractors get licenses from Cobb’s office to work in Shoshone County. It’s a misdemeanor not to follow the program’s rules.

Government bureaucracy muddied Cobb’s life for eight years while he and his staff designed the program, but he learned to make it work for him. That experience inspired him to suggest that the medical center ask HUD to guarantee a loan for a new hospital. He was counting on SMC’s healthier financial prospects through its critical access designation to help.

“HUD asked, ‘What about your Superfund site?’ I sent information, letters educating them like everyone else,” Cobb says, simplifying a process that took months and a mountain of paperwork. “They saw we had a system in place” to build without spreading contaminated soil.

Joan Head, chairman of SMC’s board of trustees, is amazed at Cobb, an SMC trustee since 1986.

“He’s so knowledgeable. It’s wonderful to sit with him, take 30 minutes of his time and learn so much,” she says. “I don’t know how we could have done this (new hospital) without Jerry and his knowledge of the valley.”

Cobb’s understanding of how to work with bureaucracy was just as important, Millard says. Administrators of small hospitals around the country visit SMC now to learn how Cobb navigated HUD’s maze, resisted frustration, explained details and put all his experience with Superfund bureaucracy into play.

“They’re absolutely a model,” Millard says. “The next hospital that goes through that process will find it a whole lot simpler because Shoshone Medical Center plowed the ground and educated the feds.”

Cobb appreciates the award from Modern Healthcare, but the real payoff for him was hearing someone at Shoshone Medical Center’s grand opening this year say there’s no longer a need to travel out of the county for hospital services.

“The new medical center is one of the good things that are happening here,” Rinaldi says. “I think it’ll do well.”