Race day ways

There’s a hotel in Spokane Valley that isn’t listed on any visitors bureau brochure.

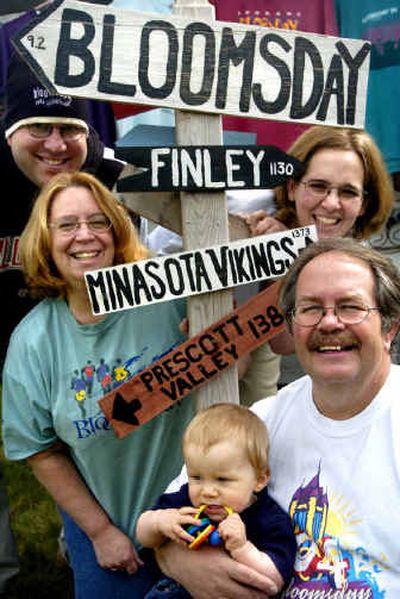

The Hotel de la Storebo opens once a year, right around the first weekend of May. That’s when 20 to 40 members of the Storebo family gather from North Dakota, California, New York and beyond to take part in Bloomsday, a tradition the family has kept for eight years now. The home is decorated with past Bloomsday T-shirts, photos from previous races and a quaint sign that reads “Hotel de la Storebo,” which greets visitors at the front door. The tradition is cherished by family members, even if it means taking back-to-back trips to the airport to pick up guests.

“The first ones come Wednesday. Then they start arriving like mad,” Pam Storebo said earlier this week.

While Bloomsday is a community tradition, a time for 40,000 people to gather for one big athletic endeavor, it’s also an excuse for individuals and families to build customs of their own. For some, like Karyn Craig, it’s a simple gesture they make year after year. She always buys a $10 pair of socks at the Bloomsday trade show in hopes that they will help her walk the 7.46-mile course faster. To others, like the Storebos, Bloomsday is an elaborate affair.

Bradley Bleck’s tradition happens at Auntie’s Bookstore in downtown Spokane. Bleck and some friends take turns reading from the James Joyce book “Ulysses,” which is about the daylong wanderings of an ordinary man, Leopold Bloom. When race founder Don Kardong created Bloomsday almost 30 years ago, he was inspired by Bloom’s adventure and by the journey described in Homer’s “Odyssey,” on which “Ulysses” is based. Joyce fans have come to refer to June 16, the day of Leopold Bloom’s adventure, as Bloomsday. Hence, the name of Spokane’s big race, even though it is held a month early.

Bleck said the annual reading at Auntie’s is on hiatus this year, but he hopes to revive it next year as a fund-raiser for the Community Colleges of Spokane Foundation.

For North Spokane resident Jude Shier, Bloomsday weekend is bittersweet. She and her youngest daughter participate in the race every year in memory of Shier’s daughter, Chelsea, who died in 1993.

“This year it falls on Chelsea’s birthday, so it’s a really important Bloomsday,” Shier wrote in an e-mail.

Dawny Taylor and her sons, ages 8 and 11, have a Bloomsday tradition, too, even though they don’t register for the race. The Taylors live close to the finish line on Broadway Avenue, and they form a cheerleading squad for runners and walkers, Taylor wrote in an e-mail.

“We sit in the front yard with the hose and offer squirts or drinks to anyone who wants them,” she wrote. “My kids have been known to draw attention to themselves by very loudly banging nails into boards with hammers. And attention they do get.”

Taylor wrote that one of her favorite parts of the tradition is being there for the last participants, the ones who cross the finish line after most Bloomies are recuperating back home.

“It’s really special to be able to be there and cheer them on, too,” she wrote. “Otherwise they wouldn’t have that cheering section.”

Another Bloomsday fan is Lisa Samuels, who lives at the corner of Dean Avenue and Lindeke Street on the final leg of the course. Ten minutes before the race begins, she and her family fill up their coffee cups and park themselves in lawn chairs in front of the house.

“Before long the lawn chairs are empty because no one can sit still from all the excitement,” Samuels wrote.

The family hollers for their doctors, teachers and the other acquaintances they see pass by, as well as for complete strangers. After the race, they have a barbecue –”rain, snow or shine,” she wrote.

“Many people just drop by and we spend the day as a family, as a neighborhood and as a community,” Samuels wrote.

Back in Spokane Valley, the Storebos also end their day with a barbecue. But the family packs in many traditions between the arrival of their first guests and when they all eventually cross the finish line.

By the end of this week, each person – including the couple’s 10-month-old grandson Lucas Lemmon – will have drawn a crayon from a sack and paid $2 to a pot. The crayons are taped to the kitchen wall next to each person’s name and after the race, when the Bloomsday T-shirt is revealed, the person whose crayon most closely matches the T-shirt color wins all the money. The process usually goes smoothly, but the year Steve Storebo dumped a box of 96 crayons instead of 64 into the sack caused some conflict. Apparently the distinctions between colors like sky blue and blizzard blue caused some debate.

Also in the kitchen are a wall of fame and a wall of shame. On the former, the Storebos post photos of family members crossing the finish line at past Bloomsdays, smiling and proud. On the latter, there are less flattering pictures of the clan.

“If you get caught eating or sleeping, you get put on the wall of shame,” Pam Storebo said.

There’s even a shot of Steve Storebo and his two brothers, who aren’t exactly petite, with their bodies crammed into a kitchen cabinet attempting some amateur plumbing.

Pam Storebo also sews a quilt of past Bloomsday T-shirts for a different family member each year. One of her quilts includes the shirt from every past Bloomsday except the years 1977, the race’s inaugural year, and 1980. Steve Storebo once saw a young boy wearing a 1977 T-shirt and asked if he could buy it from him, but the child’s father quickly stepped in to halt the sale.

In true hotel fashion, Pam Storebo puts out fresh towels and places a mint on every guest’s pillows each day – a move that earned her a plaque from her brother-in-law one year.

And during the actual race, the family keeps another custom. Although they split up so the faster Storebos aren’t held back by the slower ones, those who still are together at Doomsday Hill always stop and eat an ice cream cone once they’ve reached the summit.

Perhaps the gesture is a sign that victory is sweet, even when victory is measured in time spent with loved ones, not finishing times.