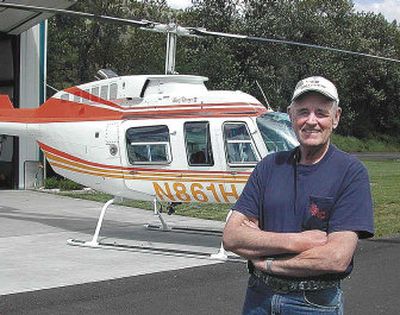

Rescuer from above

OROFINO, Idaho – When Ray Reel comes hovering onto the scene, it’s usually because bad things have happened in hard-to-reach places.

When forest fires rage in north central Idaho, Reel is there with his bucket to douse the flames or ferry firefighters to the front.

When someone is injured in the rugged backcountry, Reel makes sure medics arrive and the patients make it to hospitals.

Those who’ve flown missions with Reel say there’s something downright uplifting about how he pilots a helicopter – perhaps even spiritual.

“A helicopter doesn’t like to just sit there and hover,” says the man who’s approaching 15,000 hours of flight time, much of it linked to challenging if not harrowing calls for help.

Former Clearwater County Sheriff Nick Albers, head of the Backcountry Medics out of Orofino, has flown with Reel for almost three decades on rescues and sums up the trips this way: “It’s like he straps the helicopter on.”

Reel’s boss, Gale Wilson of Hillcrest Aircraft Co. in Lewiston, says Reel’s experience and familiarity of the landscape, especially throughout the Clearwater National Forest, make him an invaluable asset to the business as well as the community.

Friends, family and relatives recently threw what was dubbed a semiretirement party for Reel. Among those who attended were the likes of Matt Lucia and Kathie Baird, people who remember Reel as nothing less than an angel descending into their own personal hell.

“I owe him my life,” says Lucia, 34, who in late December 2000 was the only one to survive a backcountry helicopter crash that claimed the lives of the pilot and Idaho Fish and Game Department biologist Michael Gratson. Lucia, a University of Idaho graduate student at the time, was working as a wildlife technician for the department.

“I’m alive because of the skills he has and the way he can position a helicopter to find an emergency beacon,” says Lucia, who survived a night in the snow and cold.

Baird was all but dead by the time Reel maneuvered his helicopter into what some say was an impossible place during hunting season some 25 years ago. She had been shot by a Lewiston man who later said he thought she was a coyote.

“She was sitting by a campfire reading a book,” Reel recalls. He got the call while flying equipment into a lookout near Powell. Reel immediately flew to Pierce, where he picked up medical help. The team went to the site where Baird, who had accompanied her husband, Michael, and father-in-law on a hunting trip, lay bleeding and unconscious.

“She looked really bad,” recalls Reel, who carries a Bible in his helicopter. “I remember praying for her and she held on.”

At Kathie Baird’s side in the hospital days later, Michael Baird thanked his wife’s rescuers, especially Reel.

“I couldn’t believe where he landed that helicopter.”

Reel, who with his wife, Carolyn, has three grown children, learned to fly helicopters in the Army and spent five months in Vietnam at the controls of a gunship.

Most of his flights, says Reel, are within a 100-mile radius of Orofino. He estimates that he’s flown perhaps 200 rescue missions that involved serious or life-threatening injuries.

Known as a man whose quiet nature makes people really listen when he actually talks, Reel says experience is all that sets him apart from other capable pilots. And experience has taught him the most valuable lesson a helicopter pilot can learn.

“Knowing when to say no.”

He recalls the epiphany as if it were yesterday. He’d been dispatched with medics to evacuate a hunter who was injured after rolling a four-wheeler in the Bungalow area of the Clearwater National Forest. Night had all but fallen upon his arrival and darkness descended by the time Reel was ready to lift off with the hunter. Night flying anywhere is bad, Reel says. But in the backcountry, where stars are sometimes the only thing lending perspective to what’s up and down, taking off into the abyss is especially dangerous.

“Lord, if you get me out,” Reel says, recalling the prayer he recited upon easing into the air, “I won’t come back anymore.”

And he hasn’t. At least, not at night. But always when conditions are safe enough to bring others to safety.

As for retirement, Reel says he plans to continue flying through the summer and then reassess the situation. By that time, he’ll have surpassed 15,000 hours of flight time.