Entering a happier chapter

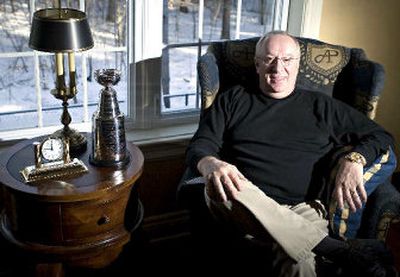

MONTREAL – Despite everything Jacques Demers achieved throughout his long and successful coaching career, he enjoys life now more than ever.

The winner of consecutive NHL coach of the year awards in 1987 and 1988 with the Detroit Red Wings, Demers lived out a dream in 1993 when he guided his hometown Montreal Canadiens to their most recent Stanley Cup.

Now running a virtual cottage industry as a TV and radio hockey analyst, he recently revealed in his French-language biography that he is functionally illiterate.

That revelation, combined with anti-anxiety medication and three years of psychiatric exploration of the ghosts of his hellish childhood and its effects, has allowed the 61-year-old a previously unknown ability to relax.

“My mind worked all the time, and it gets tiring,” says Demers, whose well-guarded secret was known until recently only by his wife, Debbie Anderson, as well as the book’s author, journalist Mario Leclerc. “Now, my mind is released. As much as winning the Stanley Cup meant the world to me professionally, I prefer to be happy.”

Anderson, Demers’ third wife, learned of his illiteracy while the couple was living in St. Louis during Demers’ stint with the Blues in the mid-1980s. She respected his plea for secrecy because he feared his pro coaching career, which began in 1972 with the WHA’s Chicago Cougars, would be ruined.

“Jacques used to be really worried about what everybody thought of him, which I guess was because he put on a big facade,” Anderson says.

Those who have seen Demers on TV notice he has papers in front of him on his desk. He can read. A little. And with great difficulty and uninterrupted concentration. The same goes for writing.

“There are words I can’t spell,” Demers says. “Sean to me was Sean Connery. You see the word spelled. You could spell it another way, S-H-A-U-N or S-H-A-W-N. You’ve got to remember, I’m asked to sign autographs. One of the toughest names for me was Jean-Philippe.”

While news of his illiteracy attracted most of the attention when the book – an English version is planned – was released, it’s the heartbreaking childhood Demers endured that tells his story. The young man learned to lie to hide the hellish reality of an alcoholic, wife-beating father.

“I don’t know if the teachers didn’t see that in me, or if they just didn’t care,” Demers says. “I can’t accuse them of anything because I can’t remember, but why didn’t they take me under their wing?”

With the help of Dr. Fernand Couillard, he gained perspective on his childhood, beginning with Demers’ first visit in December 2002.

The sessions soon made it clear that Demers had debilitating anxiety problems. Couillard prescribed anti-anxiety medication.

Initially resistant to relying on drugs for the rest of his life, Demers soon embraced their value in helping him cope with his demons.

“Since the medication, he totally changed,” Anderson says. “He was not the easiest guy to live with and he would change like this, he could get angry so fast that you’d be like, ‘Whoa! Where did that come from?’ “

The roots went all the way back to a time when spousal abuse and household violence remained behind closed doors.

“I admit it, my father was a loser, and I don’t want to be a loser like him,” Demers says. “I forgave him for what he did to me, but I can’t forgive him for what he did to my mom, because my mom never deserved anything she got – anything.”