Stop delivery

As a child, Alfred Derby watched his mother struggle with severe asthma.

He made up his mind then, at seven years old, that he would do something about it.

“I’m going to become a doctor and find the cure for asthma,” Derby recalled saying to himself.

Derby did indeed become a doctor. But he chose to specialize in obstetrics and gynecology, not pulmonology.

And when he retires later this month, he will close the doors on nearly 40 years of practicing in Spokane.

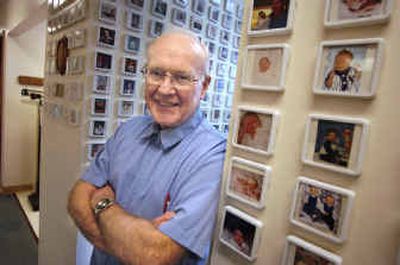

In that time, Dr. Derby has cared for hundreds upon hundreds of patients. He has delivered thousands of babies, including Spokane’s first recorded set of quadruplets.

But over the years, he also thrust himself into the center of the nation’s white-hot abortion debate, became a charter member of an armed-citizens posse, and made headlines when his estranged wife tried to burn down his house.

To his patients, though, he’s just Dr. Derby. And as news of his retirement spread, his office staff says, many of them have called in tears.

“It’s a sad day when he retires,” says Paula Freeman, a Spokane woman who has seen Derby for more than 30 years. “I don’t think we’ll find very many men like him in practice.”

Derby is 71 now and, if you squint, he looks a bit like the late Johnny Carson, with his neatly parted gray hair, trim physique and twinkling eyes. He wears a button-up shirt, jeans and loafers as he sits beside a flickering fireplace in the front room of his house, high on a hill in the Spokane Valley.

He was born in Seattle and went to high school in Walla Walla before heading west again to get an undergraduate degree in zoology at the University of Washington.

He stayed at UW for medical school (where he also took first place on the pommel horse in a gymnastics competition his freshman year). Not long after graduation, he volunteered for the physician draft into the Air Force and spent two years on Guam.

Derby wound up in obstetrics through “process of elimination,” he says.

General surgery piqued his interest most, but there were already too many surgeons, he says. So, he decided he needed to find a narrow field that he enjoyed.

When he got chosen for a military residency training program in obstetrics and gynecology in San Francisco in 1962, he found the specialty he was looking for.

But the early ‘60s were a crazy time to be in San Francisco, especially for a straight-laced military man, he says.

“The hippies were all over the place,” he recalls.

Derby returned to Washington in 1965 – this time on the East side – when he became chief of obstetrics and gynecology at Fairchild Air Force Base.

He left the military in 1968 and went into private practice, where he has been ever since.

Registered nurse Maggie Steffy has worked in Derby’s office for a quarter century.

“In the 25 years,” Steffy says, “I’ve argued with him one time.”

(A long-winded friend had kept Derby chatting while a room full of patients waited, so, Steffy says, she had to lay down the law.)

“I don’t know if I could ever work for anybody else,” she says. “It’d be very hard to train another man.”

Several other members of Derby’s office staff have also worked with him for nearly 20 years, she says.

“We’ve just all been like a family here,” Steffy says. “We’ve been through an awful lot together.”

In the mid-80s, Derby and this then-wife, Marlyn Derby, became leaders in the growing anti-abortion movement in Spokane.

Their repeated protests in front of Deaconess Medical Center landed them in jail for trespassing

Derby defended his outspoken stance in a 1989 Spokesman-Review article:

“If I were a baby and my mother was dragging me off to a butcher to rip off my arms and legs, I would hope that 100,000 people would stand in the way to rescue me,” he said.

Derby remains in the anti-abortion movement, though he’s not as active as he once was. He serves as medical director of Spokane’s Crisis Pregnancy Center and is chairman of the board of directors for Teen-Aid Inc., which promotes abstinence-only sex education.

Derby was also a charter member of Spokane’s Posse Comitatus, a group that believes citizens should arm themselves and band together to protect the community.

The group, which had offshoots around the country, has been linked to right-wing organizations, including the Aryan Nations.

But Derby says “kook balls” quickly gave the group a bad name, so he limited his involvement with the Posse.

“It never really got off the ground,” he says. “There never really was a need. It just kind of died quietly.”

In 1983, though, Derby grabbed his loaded .45 caliber automatic handgun when he saw two burglary suspects fleeing his neighbor’s home.

Derby and his wife ended up tackling the two women in a neighbor’s front yard. He popped one on the head with the side of his gun while Marlyn hit the other with a screwdriver in an attempt to subdue them until police arrived.

Derby says the police chief was set to give him a citation for his good work, until Derby mentioned the Posse Comitatus during a TV interview.

“I just became instantly politically incorrect,” he says.

Patients and those who’ve worked with Derby say that while his political views were never secret, he never forced them on others, either.

“I’ve never heard him mention it,” says Sandy Ross, 34, of Spokane, who has had three of her four children delivered by Derby.

“He’s just a very kind, Christian man,” Freeman says.

Says Steffy, “We have women come in and out who’ve had abortions. He never makes them feel bad about that … He doesn’t push his beliefs on other people, but it’s always well-known that’s what it is here in the office.”

In 1998, Derby’s private life became public when his estranged wife was sentenced to 90 days in a treatment center for trying to set fire to his house.

“We were married for 32 years and alcohol killed everything,” Derby says. The couple had two children; Lynn, a plastic surgeon, and Lance, a wine distributor. Both live in Spokane.

Marlyn Derby, a three-time candidate for Eastern Washington’s 5th Congressional seat, died in 2002.

Alfred Derby remarried about a year-and-a-half ago. KareanDerby is a labor and delivery nurse at Deaconess.

The couple can hardly leave the house without former patients recognizing Dr. Derby, she says.

“It was almost overwhelming when we first started dating,” she says.

Derby estimates that he has delivered more than 7,000 babies in his years of practicing in Spokane.

Over the years, he has witnessed numerous changes in his field.

Pain relief has come into wider use during labor, he says. Doctors have become much better at detecting potentially dangerous conditions in pregnant women. And physicians now know how to better treat certain gynecological cancers, he says.

But there have been some negative changes as well, he says, most notably the soaring cost of medical malpractice insurance.

Insurance cost about $75 a year when he was an intern in 1960. Last year, he paid $60,000, he says.

“It’s driving people out of the state of Washington,” Derby says.

Derby will miss his practice, no doubt. But he’s looking forward to retirement.

He plans to spend lots of his time with his family at a log cabin he built on 60 acres of land near Bovill, Idaho. He built the cabin in the ‘70s from trees harvested off the land. He even created a pond (known in the family as “Al’s Ocean”) and stocked it with rainbow trout.

Derby had planned on closing up shop when he turned 65, nearly seven years ago.

“It’s time,” he says. “It’s definitely time.”