Inquiry finds conflicts in U.N. program

UNITED NATIONS – The former director of the U.N. oil-for-food program had serious conflicts of interest that violated the integrity of the world body and helped undermine economic sanctions against Iraq, U.N-appointed investigators reported Thursday.

Benon Sevan repeatedly sought – and received – from Iraqi officials the rights to purchase millions of barrels of discounted oil while he was running the program, and then misled investigators about his relationship with an Egyptian national who sold those rights for $1.5 million in profits, the inquiry found.

The findings are the first to come from a panel appointed by U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan to investigate allegations that the $64 billion oil-for-food program was corrupt and mismanaged. Those allegations have led to calls for Annan’s resignation by some members of Congress and have spurred probes by five congressional committees. Those, like the probe by the United Nations, are continuing.

‘Troubling evidence of wrongdoing’

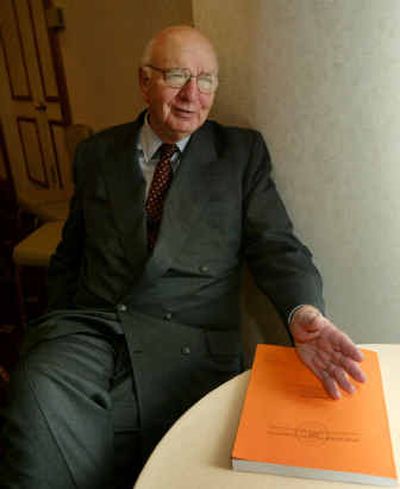

In its preliminary report Thursday, the U.N.-appointed panel, led by former Federal Reserve chairman Paul Volcker, also said that former secretary-general Boutros Boutros-Ghali was one of a few U.N. officials who improperly helped steer contracts related to the program to selected companies, and that two of his relatives were involved in the sale of the oil allocated to Sevan.

Annan announced that he will pursue “disciplinary proceedings” against Sevan and another U.N. official, Joseph Stephanides, who allegedly helped the British government circumvent the United Nations’ competitive bidding process to steer a contract to a British company. Stephanides did not respond to a request for comment.

Annan said Volcker’s report contains “extremely troubling evidence of wrongdoing” by Sevan.

“Should any of the findings of the inquiry give rise to criminal charges, the United Nations will cooperate with national law enforcement authorities pursuing those charges, and in the interests of justice I will waive the diplomatic immunity of the staff member concerned,” Annan said.

Report due on Annan’s son

Annan noted that he is awaiting a report by Volcker probing possible wrongdoing by Annan’s son, Kojo, who received $150,00 over a five-year period from a Swiss company while it profited from the oil-for-food program. The company maintains that Kojo Annan, who had been an employee, had nothing to do with its work in Iraq and that the payments were part of a standard agreement that would bar him from working for a competitor.

Sevan’s attorney, Eric Lewis, said that “Mr. Sevan never took a penny” from the program. Volcker’s commission has “succumbed to massive political pressure and now seeks to scapegoat” Sevan, Lewis said.

“Mr. Sevan’s goal throughout the life of the program was to expedite the pumping of oil in order to pay for urgently needed humanitarian supplies” in Iraq, he said.

Congressional criticism

Some in Congress viewed Volcker’s report as vindication of their criticism of the organization. Rep. Henry Hyde, R.-Ill., chairman of the House International Relations Committee, said the findings “reinforce evidence we have developed detailing lapses in program oversight, management, fiscal controls and an absence of even the most rudimentary standards of accountability.”

Sen. Richard Lugar, R-Ind., chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee, said that “part of the blame for the current imbroglio lies with the U.N.,” but “we must recognize that those nations who sat on the Security Council … during the life of the program – and this includes the United States – must also answer questions as to why they, too, did not pay greater scrutiny to this program.”

The United Nations established the program in December 1996 to allow Iraq, which had been put under U.N. sanctions after its 1990 invasion of Kuwait, to buy food, medicine and other humanitarian goods.

The program helped ease the plight of millions of undernourished Iraqis, but it also provided the Iraqi government with at least $2 billion in illicit kickbacks and payoffs, according to a report last year by CIA adviser Charles Duelfer. Volcker said that the government received far more in illicit funds from unauthorized oil sales outside the oil-for-food program to Jordan, Turkey, Syria and Egypt.

Volcker’s report also said U.N. auditors had “inadequate” resources and staff to conduct a proper investigation of the program, and it charged that the United Nations violated its own competitive bidding practices in 1996 when it selected three companies – BNP Paribas of France, Saybolt Eastern Hemisphere BV of the Netherlands, and Lloyd’s Register Inspection Limited of Britain – to monitor Iraq’s trade.

‘Most disturbing finding’

Boutros-Ghali, of Egypt, acting on the instructions of the Iraqi government, helped steer a banking contract to hold Iraqi’s oil revenues to BNP, the report said. “When provided with the short list, he contacted the government of Iraq and asked for its choice,” the report said. “Apparently the Government of Iraq indicated a preference for BNP, and the secretary general acquiesced.”

Boutros Ghali could not be reached at a number in Paris provided by the United Nations.

Volcker said the “most disturbing finding” is that Sevan solicited oil for a small company headed by an Egyptian relative of Boutros-Ghali’s. A brother-in-law of Boutros-Ghali “was a likely intermediary” between the two men, the report said.

Sevan championed Iraqi initiative

Shortly after he was appointed to run the oil-for-food program in October 1997, Sevan championed an Iraqi initiative to allow Iraq to use its oil profits to buy $300 million worth of spare parts to repair its oil infrastructure. Two days after the U.N. Security Council adopted the proposal in June 1998, Sevan traveled to Baghdad and asked Iraq’s oil minister, Amir Rashid, to grant an associate rights to buy discounted oil, the report said.

The Iraqi government granted the oil company headed by the Boutros-Ghali relative rights to buy 1.8 million barrels of oil, which were sold for a profit of $300,000.

The report continued with the following account:

Sevan subsequently made a similar request, but the Iraqis cut the oil allocation to 1 million barrels to express disappointment with his failure to counter U.S. efforts to block the export of some spare parts.

‘Continuing conflict of interest’

Sevan returned to Iraq in the summer of 1999 with a fresh proposal to expand the spare-parts arrangement. Within five days of his departure, Iraqi approved the rights to buy 2 million barrels of oil, which the oil company sold for $500,000 in profits.

Volcker’s team has not proved that Sevan received money from the company’s oil deals. Volcker is examining cash payments Sevan received between 1999 and 2003 amounting to $160,000. Sevan has filed U.N. financial disclosure forms saying the money came from his aunt, who died last year after falling into an elevator shaft.

“Her lifestyle did not suggest this to be so,” the report said. “She was a retired Cyprus government photographer living on a modest pension.”

“Mr. Sevan placed himself in a grave and continuing conflict of interest situation,” the report concluded. “The Iraqi government, in providing such allocations, certainly thought they were buying influence.”