Engines of change

Ed Willey shakes his head when he hears people complain about job prospects.

“Send them to me,” he says with a laugh. “We’re the best-kept secret in town!”

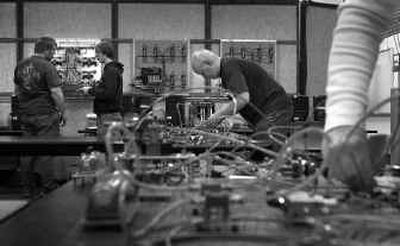

With the enthusiasm of an Army recruiter, Willey runs a little-known program at Spokane Community College that teaches students about the intricacies of hydraulics and pneumatics. In plain words, students learn how modern machines work, how to design them and how to fix them.

The reward is a two-year degree that throws open the door to good-paying jobs around the world.

As Willey puts it: “Automation is the backbone of the economy, and we teach our students all about it.”

Some graduates are moving on to jobs designing and building hydraulic cylinders for the new Airbus A380 jet through a company in Yakima.

Others, like Eric Wellington, took an industrial sales job for an aerospace company outside of Everett. He hurt his back on a previous job and wanted to apply his interest in machinery to sales.

Student Matthew Merritt recently flew to Salem, Ore., to interview for a job.

Now 30, he had worked for seven years as a welder. His pay topped out at $11.50 an hour, so he decided to work construction. Lean winters with little work and summer burnout led him to SCC, and eventually Willey’s hydraulics program.

“It’s more than I could have hoped for,” he says.

Now nearing the end of his second year, Merritt expects to earn more than $16 an hour in his first job.

“It’s basically the other way around — employers are trying to impress the students in this class because they want to hire us,” he says.

Called Hydraulics and Pneumatics Automation Technology, the SCC program focuses on the use of fluid power in modern machines. Most every machine involved in making and packaging goods, from frozen peas to circuit boards, are run using compressed air (called pneumatics), or pressurized oil (called hydraulics).

Students spend an intense first year of classes studying theory, math and communication skills needed for work place success. The second year is spent working on projects and internships where students can practice what they’ve learned.

Upon graduation, firms are lined up to hire.

The pay can start at $18 an hour, but some of Willey’s students earn double that within years, he says.

Yet the program is underused. With less emphasis placed on vocational education at area high schools, there are fewer students routed to the program and its promise of high-paying jobs.

“It’s a shame,” Willey says. “It’s like walking past a $20 bill lying in the parking lot without picking it up.”

The program has room for about 70 students and admission is not competitive.

The studies are difficult and students tend to form bonds within the program that later turn into good friendships and professional networks, Wellington says.

Despite the stereotype of industrial machinery being men’s work, women graduates have been very successful, he added.

“Our industry is not gender specific,” Willey says. “I don’t really care if you’re a man or woman. If they want to be successful, we can help them. Welcome.”

Of the graduates in recent years, more than half found work in the Pacific Northwest.

In Spokane, graduates have gone to work at big factories. Others are working for businesses like Pacific Power Tech.

“We take on graduates, sure,” says Bruce Karels, operations manager for the company’s Spokane arm.

Hydraulics graduates with Pacific Power Tech might work with saw mills or mines where hydraulic machines are used. In the Seattle area, hydraulics workers help with Boeing Co. projects and design and maintain the ferry terminal ramps that allow drivers to bring their cars onto the boats.

“We do sales, system design and also service and repair,” Karels says.

Some graduates go to work for firms with international operations. Willey has students that helped run the massive tunnel-boring machines that dug under the English Channel to link Great Britain to mainland Europe.