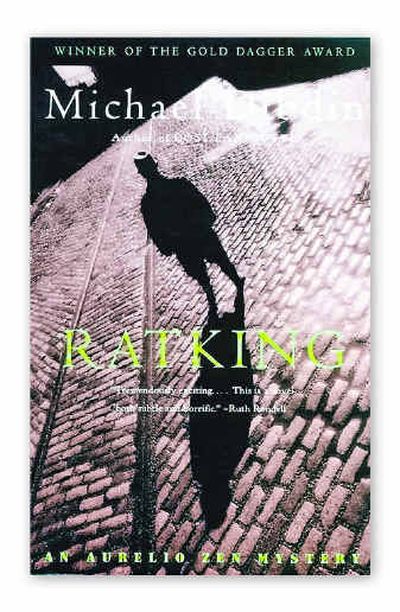

Michael Dibdin’s ‘Ratking’ selected for January

Aurelio Zen is no East Indian guru.

He is, instead, a fictional Italian police investigator who is the central character of a mystery series that is as original as it is illuminating.

Zen is the creation of Michael Dibdin, a 57-year-old Irish-born author who lives in Seattle with his wife, the author Katherine (“K.K.”) Beck.

And he’s the central character of “Ratking” (Vintage, 272 pages, $12 paper), a mystery that is the January reading selection for The Spokesman-Review Book Club.

Dibdin, who was raised in England, has written nine novels that feature Zen as the protagonist. Each is set in a different part of Italy, from the Umbrian city of Perugia in 1989’s “Ratking” to the Italian Alps in “Medusa” (Pantheon, 320 pages, $23 hardback), which came out in February.

In addition to demonstrating an impressive knowledge both of Italy’s language and its culture, Dibdin has invented a character in Zen who is as richly nuanced both in neuroticism and morals as the detective himself is dogged at investigating cases within an atmosphere of crushing corruption.

Something of a mama’s boy, whose inability to embrace intimacy is matched only by his need for it, Zen navigates as well as he can between superiors who want him to fail and the criminals he pursues, who often have mysterious connections with powerful forces.

“What makes Zen different … is his willingness to accept corruption,” says a reviewer for the literary journal Booklist, writing about Dibdin’s set-in-Venice novel “Dead Lagoon.”

“(L)ike Roman Polanski’s Chinatown, Venice is a place that resists clarity, and when it is imposed, tragedy usually results. Classical detective stories end with order-restoring solutions; Dibdin novels end with truth as an agent of chaos. Neither hard-boiled nor cozy, the Zen series has claimed its own turf: murky reality.”

In an interview with januarymagazine.com writer Linda Richards, Dibdin said that he never intended to make Zen the focal point of a series. He merely wanted to write a novel – which became “Ratking” – that included his own Italian experiences, which he had gained first as a teacher of English as a second language.

“I invented the Zen character for that book, but I wasn’t really particularly interested in him, so there wasn’t really a lot about him,” Dibdin said. “He’s really just a facilitator who comes in and makes it possible for other things to happen.”

In “Ratking,” Zen is sent to Perugia to investigate the murder of a wealthy industrialist. What he discovers there is a situation that is as politically sticky as the crime is sordid. To make things worse, there are more suspects than Zen can deal with, many of them members of the dead man’s own family.

Survival, as Zen quickly learns, is what everyone is after – he being no different.

As one character explains, “A ratking is something that happens when too many rats live in too small a space under too much pressure. Their tails become entwined and the more they strain and stretch to free themselves the tighter grows the knot binding them, until at last it becomes a solid mass of embedded tissue. Most of the ratkings they find are healthy and flourishing … have evolved some way of coming to terms with their situation.”

To solve the crime, then, Zen must find a way to get the suspects to turn on each other. Which, of course, they end up doing.

“Tangled tales,” said Guardian reviewer Linda Taylor, “are Dibdin’s specialty.”

The author’s own life is more straightforward. In fact, Dibdin is a perfect example of someone who took advantage of what life threw at him.

Educated in both England and in Edmonton, Alberta, he gave up on graduate studies to pursue writing. When a rich relative died, leaving him and his father a house in London, he moved there and wrote what became his first novel, a 1978 mystery titled “The Last Sherlock Holmes Story.”

Not interested in doing another Holmes-based book, he ended up getting a certificate to teach ESL. He snared a job in Italy (in Perugia, actually) and began soaking up the culture. The Zen books, which have been translated into more than a dozen foreign languages, are the result.

Dibdin has written a half-dozen other mysteries, too. He’s even edited and written a commentary for a collection of crime-themed short fiction. Clearly, though, his most successful creation is Zen, a complex character whom Dibdin describes with language that is as rich as it is perceptive.

In “Ratking,” for example, a middle-aged man from Verona shares space with the detective on a train.

“He turned to the third occupant of the compartment,” Dibdin wrote, “a distinguished-looking man of about fifty with a pale face whose most striking feature was a nose as sharply triangular as the jib of a sailing boat. There was a faintly exotic air about him, as though he were Greek or even Levantine.

“His expression was cynical, suave, and aloof, and a distant smile flickered on his lips. But it was his eyes that compelled attention. They were gray with glints of blue, and held a slightly sinister stillness which made the Veronese shiver. A cold fish, this one, he thought.”

Maybe. But this is one cold fish who dwells at the heart of a hot mystery series.