His canvas keeps growing

THE MOOSE MOUNT peering over Leon Roulette’s living room is in the same crowd dead as when it was alive.

Elk, deer, even grizzly bears and wild sheep share the moose’s indoor home and suggest the presence of a passionate hunter. Leon, in his jeans and flannel shirt, proudly claims the title, which, he’s quick to point out, he shares with his wife, Carolyn Parker.

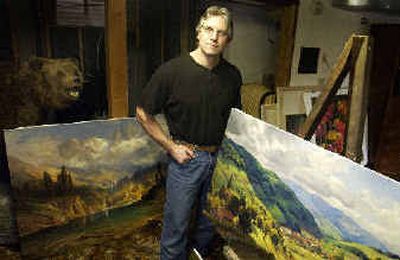

Everything about Leon, 45, and Carolyn and their 20 acres in Garwood screams hearty Idaho, so Leon’s romantic paintings of French street scenes and colorful bouquets of dahlias are as unexpected as a hot day in January.

“Landscapes, still life – there’s not one favorite thing I like to do,” Leon says, sliding his 6-foot-plus body into a heavy dining room chair. “I adapt to whatever’s the rage, but I want to make sure there’s me in all the stuff I do.”

The healthy sales of Leon’s paintings in galleries throughout the nation are relatively secret in the Panhandle, where no galleries exhibit his work. Leon is as comfortable with oil paints as he is with a hunting rifle, but few Idahoans know it.

Before he ever laid eyes on Idaho, Leon belonged here. The mountain man inside him ached for release while Leon was still in Southern California making prints of other people’s art. His name wasn’t even Leon Roulette then, but Greg Parker.

“Leon Roulette’s my art name. It sounds better,” he says, grinning. Leon was his middle name. Roulette was his mother’s maiden name. The nom d’art promised better marketing of his oil paintings than Greg Parker, and Leon believes in good business.

Clearwater Publishing dropped him in Idaho with Carolyn in 1996.

“We were plotting how to leave Southern California,” Carolyn says, as she stacks building blocks with their toddler daughter, Emma, on the carpet.

Leon’s artwork was just taking off in 1996. He’d lived for art ever since he discovered his dad’s paints and brushes when he was 5. Leon’s dad died from ulcer complications in 1962. He was a pharmacy salesman who painted as a hobby. Leon treasures the single work – a respectable painting of two Scottish terriers – he has of his father’s.

By high school, Leon had absorbed as many library books about Dutch masters, such as Rembrandt and Jacob van Ruysdael, and French Impressionists as he could. He knew art’s masters, language and styles. The more he read, the more he wanted to know. His mother encouraged his art, but Leon kept his work to himself. He sensed that art wasn’t a serious undertaking in many people’s minds.

“It was highly personal,” he says.

“My dad calls him a posy painter,” Carolyn says, chuckling.

Leon’s practical side overpowered his need to experiment in art as he became an adult. He found a job with Clearwater Publishing creating arduous silk-screenlike copies of fine art – serigraphs. He made editions of other artists’ original works for private homes, galleries and publications, and painted his own art after work.

“He’d come home and paint all weekend long,” Carolyn says. Leon finished a painting nearly every week.

Eventually, Leon quietly showed his work to some of the gallery owners he met through Clearwater. He was painting loosely realistic scenes with bold, energetic strokes and splattering Day-glo paint over part of the canvas for an abstract finish. His painting of a lake and mountains, for instance, blends comfortably into a colorful splattered area that suggests a tangle of rushes, cattails and water insects.

A gallery in Laguna Beach, Calif., began carrying his work under his nom d’art. By 1996, Leon was earning $4,000 to $5,000 a month from sales of his art. The money pleased his practical sense. It also boxed him in. He couldn’t convince himself to stop producing his popular style even after he’d evolved past it.

A hefty new mortgage in Garwood didn’t help. Clearwater had decided to leave Southern California in 1996 for a new home in Hayden. Leon managed the small company that had found a profitable niche with clients in Japan. He and Carolyn moved confidently, bought 20 wooded acres thick with wild elk, deer and grouse and threw themselves into remodeling the property’s 25-year-old house into their rustic hideaway.

But two years later, Clearwater closed, sending Leon and Carolyn into a panic. They didn’t want to leave Idaho or their perfect setting, but they needed more of an income than Leon’s paintings earned. Carolyn, a biochemist, took a job with a lab in Post Falls. Leon hired an agent and threw himself into painting full time.

“His dream was to end with the company and paint full time,” Carolyn says. “You have to be careful what you wish for.”

A return trip to California confirmed their decision to stay in Idaho. Leon and Carolyn couldn’t handle the traffic, crowds or congestion.

“It was like our worst nightmare,” Carolyn says.

Leon produced more of his popular, slightly abstract Day-glo art for the Laguna Beach gallery, but sales were slowing.

“Martha Stewart pushed class, made people want nicer things,” he says. “I was painting to society’s cheap taste, but I like doing moody, realistic Impressionism.”

His agent encouraged him to try styles that pleased him, so Leon painted old boat and harbor scenes with wide, quick brush strokes and variations of light. People liked the work, so Leon tried French street and café scenes in the style of early Renoir. Light intrigued him. He painted sunlight streaming in windows and dappling walls, floors and furniture.

His agent found a dozen galleries coast to coast that wanted to exhibit Leon’s work. His show closest to home was last month at the Douglas Gallery in Spokane. Danni Douglas, one of the gallery’s owners, was delighted with Leon and his work.

“People identify with him. He’s such a down-to-earth guy,” she says. “His art just pulls people into it. We sold probably nine or 10 out of 30 paintings. People recognize the quality.”

Leon’s Spokane show closed Dec. 4, but the gallery still exhibits his work. Some are copies Leon paints himself of some of his most popular originals – bright Iceland poppies, dahlias, a French café.

Leon has moved on to wine country scenes, suggested by a patron who loves vineyards. He finishes 40 to 45 paintings a year and believes he’s still evolving.

“The more I know, the less I know,” he says, smiling. “Painting is like a symphony. How do they get it all to work?”

When he’s not painting, Leon raises beef cattle or installs 250-pound kitchen sinks, granite countertops and slate floors. Or he hunts.

“I don’t think we’ll ever leave this area,” he says, pointing out the ice-covered pond and wooded hills through the picture windows in his living room. “We knew we belonged here.”