Detectives in training

When students enter Dennis Mucenski’s forensics class at a high school in Pittsford, N.Y., they walk right into a murder mystery. They scan the crime scene looking for clues and examine hair and fibers. They test fingerprints and blood types. Then it’s up to the teens to solve the murder mystery during the half-year course, using skills they’ve learned as forensic scientists. At the end of the semester, they present their evidence to reveal who killed the fictional Joey G.

In the past few years, television shows such as “CSI,” “Forensic Files” and “Law & Order” have put forensic science on the radar of teens — and their teachers. High school students say they watch the shows because the stories are captivating. But the fictional mysteries leave them wanting to know more about the science of solving crimes.

“Kids are responding because they are excited about the subject, the class and the teacher,” says Jim Hurley, director of development at the Colorado Springs, Colo.-based American Academy of Forensic Science, a nonprofit professional organization. “This is a subject that’s real to them. They can see how what they’re learning is used in the real world and how it makes a difference.”

The goal of Mucenski’s lab-based course is to help students become more familiar with scientific tools, such as microscopes and forceps, and to get students more involved in hands-on science lessons.

“The great thing about the course is that the students are highly motivated because they see it all on TV,” Mucenski says. “But what they don’t realize is that they’re getting tons and tons of science, too.”

Tristina Durett, 17, held a yardstick in place above a lab table at another area New York high school as her classmates took turns releasing drops of fake blood (made of water, corn starch and red stain) from different heights. The idea was to show the difference between blood patterns on the newsprint below.

“You can tell how people are shot by the way their blood splatters,” explains Lindsey Mease, 16. After watching shows such as “CSI,” Lindsey says she wanted to learn more about how scientists use technology to solve murders.

More than 100 students at her school are studying forensics. The half-year course is a growing science elective at more and more area high schools.

“Forensics is hot,” says John Domesick, spokesman for Court TV, the cable channel that created the hit show Forensic Files. “There’s been an explosion of interest on the subject that crosses all lines.”

In response to a flurry of requests received from science teachers, Court TV in 2002 launched “Forensics in the Classroom,” a free curriculum supplement for high school students and teachers. The network had hoped to reach at least 1,000 teachers interested in teaching forensic science. But by December, more than 22,000 teachers nationwide had registered for the free lesson plans, reaching at least 2 million students, Domesick says.

In the Greece Central School District, as with a growing number of districts in the Rochester, N.Y., area, the course was launched to offer students another option to meet state Regents science requirements, says Lisa Buckshaw, the district’s math and science director.

High school students in New York must earn three science credits to fulfill graduation requirements, Buckshaw says. To accomplish that, each student must complete two Regents science courses, pass one Regents exam and take a living environment course, she says.

“Many of our students aren’t necessarily taking forensics for a graduation requirement, but are taking it based out of interest,” Buckshaw says. “That’s so great to see.”

Since Greece launched a semester-long forensics class in 2002, enrollment has doubled.

“The course has a huge biology and chemistry base and has generated huge interest among students,” said Buckshaw.

Tristina was drawn to the class because it wasn’t like a regular science class.

“You do lots of labs to learn about blood types, crime scenes and things that scientists actually do to solve crimes,” she says.

In addition, students often watch parts of some of the popular TV shows in class to drive home a lesson, says Patrick Case, a forensics teacher.

Dan Heffernan, 17, who wants to work for the FBI, says he’s glad to have a good basic knowledge of criminology. But he noticed that class lessons are quite different from the TV shows.

“There are so many aspects of the show that are sped up. It takes a little longer to do everything in real life than it does on the show.”

For example, on TV, forensic scientists can scan a fingerprint and instantly find a match from those on file. In the real world, Dan says, such a task would narrow down the field considerably, but finding an instant match would never happen.

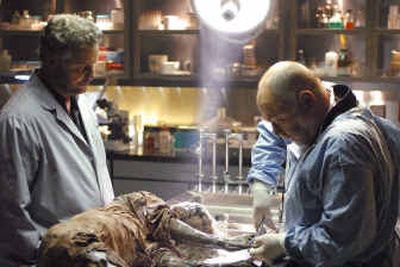

When it was time to examine hair recovered from Mucenski’s faux crime scene, juniors Kim Peters, Brittany Belt and Katie Ward, all 16, lined up three microscopes to inspect the evidence in detail. They would compare the hair from the scene with suspects’ hair.

“I thought I’d want to be a crime scene investigator,” Ward said. “But now? No way. You have to be so careful with evidence and it’s so tedious. It’s not like “CSI” at all.”

Students need to pay attention to detail in class or risk messing up, Ward adds. “And that’s not something you want to do when someone else’s life is in your hands.”