Lewis sees football as easy after prison

ATLANTA – Two-a-day practices in searing heat. Monotonous meetings. Curfews. Suddenly, NFL training camp is inviting to Jamal Lewis. It sure beats prison.

“Football season will be nothing now,” the Baltimore Ravens’ star running back said Friday, a day after he was released from a federal prison camp in Pensacola, Fla., where he was locked away for four months as part of his sentence for using a cell phone to help facilitate a would-be drug deal in July 2000.

“I thought training camp was the hardest thing. But going through this now, it will be a breeze.”

Lewis, 25, won’t attend the voluntary Ravens minicamp that begins today, and it is uncertain if he will be allowed to attend mandatory camp next week. His sentence includes a two-month stay at a halfway house near the downtown hotel where he addressed the media, with a scheduled early August release that would force him to miss a couple of days of two-a-days.

A request for Lewis to be assigned to a halfway house in Baltimore was rejected by the Federal Bureau of Prisons, leaving the Ravens to hope he will be granted a pass to attend next week’s minicamp.

“We hope to communicate with the authorities that there are things he has to do now to not put himself at jeopardy physically,” said coach Brian Billick, who joined Lewis at the news conference with general manager Ozzie Newsome and team President Dick Cass. “This is a unique business, so this isn’t an everyday case. But there’s some very pivotal things, with regard to rehab, that need to become much more aggressive. He needs to get into football shape, and that has to be done in a certain environment.”

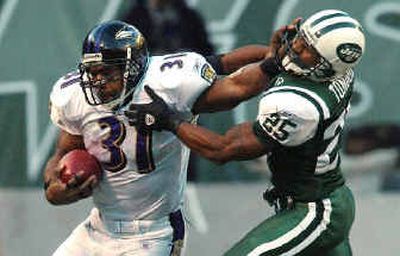

Billick and other team officials characterized Friday’s session as an important step in moving beyond the series of events that landed one of the NFL’s top players behind bars. Lewis was the league’s offensive player of the year in 2003, when he became the fifth player in NFL history to rush for 2,000 yards in a season and set a single-game record with 295 rushing yards.

“I don’t think that I’m a victim,” Lewis said. “I did my time for what I did. I don’t have any bitter feelings for the government, the prosecutors or anything. I stood up for what I did.”

Lewis pleaded guilty to a lesser charge in October as a more serious drug conspiracy charge (which carried the possibility of a 10-year sentence) was dropped. He served a two-game NFL suspension last fall, which cost him nearly $761,000 in salary.

The case stemmed from an FBI sting operation in the summer of 2000 – after the Ravens drafted Lewis fifth overall and weeks before he signed an NFL contract and reported to his first training camp. According to The (Baltimore) Sun, citing an FBI affidavit, an informant called the Atlanta native on his cell phone and in a secretly recorded conversation arranged for a meeting with his longtime friend, Angelo Jackson. The three met at a restaurant where, according to the affidavit, a price for a supply of cocaine was discussed.

Jackson was arrested when attempting to purchase the drugs; Lewis was accused of facilitating contact between Jackson and the informant.

“The lesson learned is that you have to pick your friends wisely and watch every move that you make,” Lewis said.

Although the Ravens and Lewis’ attorneys have questioned the timing of charges filed in the case nearly four years after the crime and the judge who presided over his plea agreement hearing suggested the prosecution’s case was weak, Lewis’ reputation is tarnished nonetheless.

“I think the only thing you have is your name,” Lewis said. “It might have been tarnished a little bit … but it is what it is. Things happen. I’m looked at with a magnifying glass. … I’ve put this behind me, and I’ve moved on.”

On a football field, Lewis is an uncanny blend of speed and power. In the minimum-security prison, he never considered himself special and didn’t do autographs. He shared quarters that housed 12 inmates, was awakened at 4:30 each morning, was counted three times daily and constantly was watched over by guards. Like most inmates he performed a job, passing out equipment in the tool shed.

It might not have been hard labor, but the experience gave Lewis a fresh perspective on freedom.

“It has been a hard transition,” Lewis said. “Some people think that just because it’s four months, that’s not a long time. But going day to day, that is a long time. That gives you a lot of time to think and reflect on things that are really important.”

Before reporting to prison, Lewis told teammates not to visit.

“I know how it is in the offseason, trying to get everything done, being with your family,” he said. “But after being there two or three weeks, it was like, ‘I wish one of these guys would come and see me.’ “

Teammates, including Deion Sanders, visited. So did Newsome, position coach Matt Simon and team owner Steve Bisciotti. Not a weekend passed when Mary Lewis didn’t see the youngest of her two sons.

This is the same Mary Lewis who worked for 28 years for the Georgia Department of Corrections, starting as a counselor and working her way up to warden of a halfway house.

With “tears of joy” in her eyes Friday, Mary Lewis issued a promise: “When Jamal gets back on the field, he’s got something to show all of the world.”

Said Jamal, “I’m in great shape. I got a lot of rest. Four months of rest. … I just can’t wait to really get to working out.”