Arnie will always be No. 1

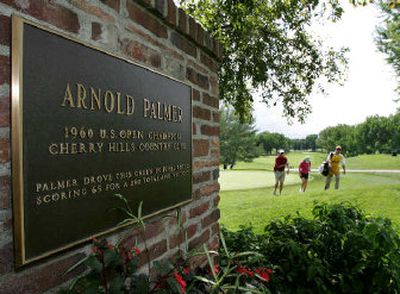

CHERRY HILLS VILLAGE, Colo. – The brick monument set to the side of the tiny first tee box beckons as both an honor and a challenge.

It honors Arnold Palmer, who hit the shot of his life from that elevated location at Cherry Hills Country Club.

It challenges anyone who hits a shot from there ever more.

This week, the 156 players entered in the U.S. Women’s Open will get their chance. Today’s opening round will be their first chance.

“There’s no point in hitting driver because there’s no chance,” Laura Davies insists.

But heading into the final round of the 1960 U.S. Open, Palmer figured it was worth attacking the green on the 313-yard, par-4 hole. So, he hitched up his pant legs, grabbed a driver and cranked the ball through the thin, mile-high air. It flew about 300 yards, bounced hard in the rough and trickled out, onto the green.

The result was the first of four straight birdies, the beginning of what still stands as the greatest comeback in U.S. Open history.

“Actually, I hit it so good, I wasn’t sure it wouldn’t go over the green,” Palmer said Wednesday in a telephone interview from his office in Latrobe, Pa. “So, I was happy to see it hit in the rough and go onto the green.”

That Palmer, the gambler’s gambler, would take such a chance and produce one of the best shots in the history of golf wasn’t a given until a lunchtime conversation with golf writers Bob Drum of the Pittsburgh Press and Dan Jenkins of the Fort Worth Press.

Back then, the final two rounds were played Saturday, and after his third round left him seven shots out of the lead, Palmer went to lunch and asked the writers how far a 65, which would leave him at even-par 280, might go toward winning the tournament.

“Doesn’t 280 always win the Open?” Palmer said.

“Two-eighty won’t do you a damn bit of good,” Drum replied.

Infuriated, Palmer left his hamburger at the table and stormed off to the first tee.

His eagle putt went 2 feet past the hole and Palmer settled for birdie. Still, the tone had been set. Palmer’s four straight birdies helped him to the 65 he had predicted. The seven-shot deficit he made up still stands as the greatest final-day comeback in U.S. Open history.

Forty-five years later, Palmer said he still believes the shot on No. 1 at Cherry Hills is the one he will always be singularly identified with.

Could someone else become a part of that history this week?

A generation ago, no woman would think about making the shot. But the players are better, and so is the equipment, and the hole, which has been lengthened by about 30 yards, is eminently reachable for the top players.

During practice rounds, fans crowded around the first hole to watch the top players hit.

Despite being egged on, Annika Sorenstam simply pulled out a 4-iron and hit a shot safely down the middle of the fairway.

Michelle Wie went for it, but came about 15 yards short, into the thick rough, and later conceded that she probably won’t do it once the shots start counting.

“I don’t think that’s the right play there,” she said.

If there’s any player who might take a chance, it would figure to be a big hitter like Davies, but she doesn’t think the risk is worth it. The rough in front of the green is 4 inches long, much gnarlier than it was in Palmer’s day.

“If they had cut the rough down in the front edge, it might be worth it,” she said. “But there’s no point leaving it 20 yards in that stuff.”

Arnie’s advice if he were on Davies’ bag? Take a wild guess.

“You don’t have to ask me that,” Palmer said.

He conceded, though, that “it takes a certain personality” to try to drive a par-4.

Certainly, the King had it.

He was at his peak in 1960. The win at Cherry Hills gave him the first two legs of the grand slam and was the third of seven major championships he won in a seven-year span.

“Arnie’s Army” was taking off and Palmer was bringing a game for blue bloods and the country-club set straight to the common man.

It was gambits like the one he took on No. 1 at Cherry Hills that made it happen.

Today, besides the plaque and the rough, which is a little higher, the hole looks essentially the same as it did in 1960. A small ditch runs along the right side. It was that same ditch that Palmer hit into on his first shot of the tournament, en route to a double bogey.

“I felt like I had a chance to win the Open, and starting off with that happening is rather upsetting,” he said.

A few years after his victory, Palmer was called on to help redesign the golf course and, oddly enough, he wanted to move the tee box to a spot from where the green could not be reached.

He said his friends at the course talked him out of that move.

“They said, ‘Arnie, you made the hole famous. Put it back where it was,’ ” Palmer said. “They objected to that, and I’m happy they did.”