Digital dilemma

PARIS — The world according to Google?

Europeans have long bemoaned the influence of Hollywood movies on their culture. Now plans by Google Inc. to create a massive digital library have triggered such strong fears in Europe about Anglo-American cultural dominance that one critic is warning of a “unilateral command of the thought of the world.”

For Europeans, the fear is that the continent’s contribution to the pillars of recorded knowledge will be crushed by a profit-oriented California company — and may end up presenting a U.S.-centric version of the world’s literary legacy.

Google’s ambitions are grand — if a bit more modest than the hostile corporate takeover of the tiller of world literature that many critics seem to be imagining.

The project, announced in December, involves scanning millions of books at the libraries of four universities — Oxford, Harvard, Stanford and the University of Michigan — as well as the New York Public Library and putting them online. It will take years to complete.

So great is the concern that six European leaders have jointly proposed creating a “European digital library” to counter the project by Google Print, as the new venture is known. Other countries are expected to come on board.

Failing to digitalize — declared the heads of state in France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Poland and Hungary in an appeal to the European Union — is to risk that “this heritage could, tomorrow, not fill its just place in the future geography of knowledge.”

Jean-Noel Jeanneney — who as president of the French National Library oversees a collection of 13 million books — presented a vision of Google potentially hijacking “the thought of the world” in a book he published this week entitled, “When Google Challenges Europe.”

“I think that this could lead to an imbalance to the benefit of a mainly Anglo-Saxon view of the world,” Jeanneney said in a telephone interview. “I think this is a danger.”

He noted that French cinema thrives only because the government took steps to ensure its survival against an American onslaught.

Peering into the future, the critics see an age where if you can’t be found on Google you’re nobody. That may be OK for the likes of Dante and Shakespeare, but many fear lesser known authors would suffer.

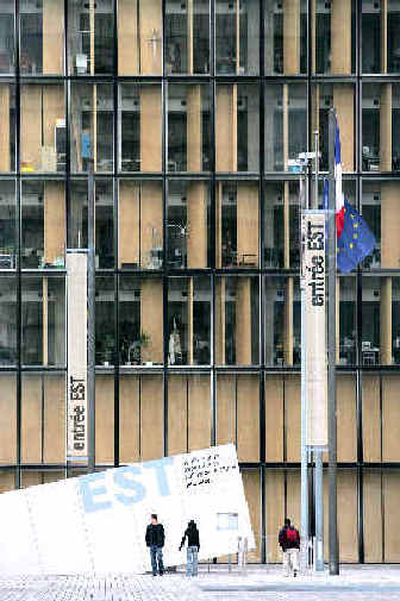

“There is increasing concern, I think, that something not registered on the Net will not be seen as existing,” Hungarian Culture Minister Andras Bozoki said in an interview during a European culture forum this week in Paris. A European project would provide a “voice” for smaller countries and their literature, he added.

While giants of Hungarian literature, for instance, are most certainly on the shelves of the libraries on Google’s digitization list, they might not make the cut in the selection process — or perhaps only do so in translation. Or take, for example, the 19th century writer Cyprian Norwid, a favorite of the late Pope John Paul II. Will Google provide his poetry in the original Polish?

Many works that the French consider sources of cultural inspiration for Europe and beyond could also miss the cut in a market-oriented selection system, Jeanneney said.