PEDALING A TRADITION

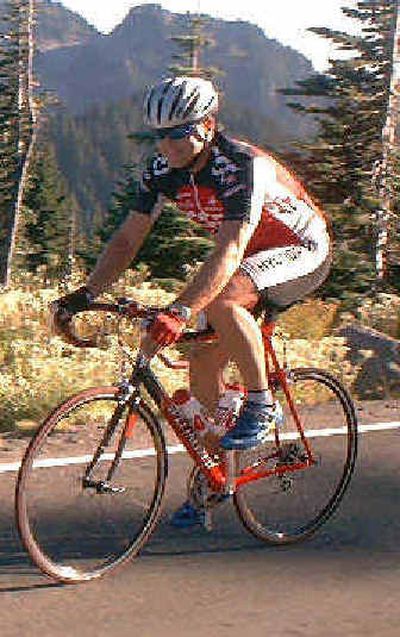

For three decades, Mark Buescher has planned much of his life — job selection, the birth of his children, you name it — to maintain the tradition of getting a sore butt on the third weekend in May.

Next weekend, Buescher plans to claim the record for the longest participation in the Tour of the Swan River Valley when he rides for the 30th time in the pack of bicyclists to celebrate the tour’s 35th anniversary.

Pedaling 230 miles in two days out of Missoula was kid stuff at first. Now the event, and all the training that goes into it, has the 44-year-old Spokane respiratory therapist freewheeling toward middle age with thighs of steel —not to mention a posterior callous that must rival the leathery padding on the feet of African tribesmen.

“Last year I rode 1,600 miles in the spring to get ready for TOSRV,” Buescher said, adding that he takes a week of vacation at the end of April each year to pile more mileage onto his bike odometer.

This year, because of the mild winter, he’ll likely have more than 2,200 miles heading into next weekend.

Few of the 300 or so participants show up that well prepared. After all, TOSRV West is a fun-style ride, not a race.

It’s a bicycle social and progressive dinner. Some riders, like Buescher, just breeze through it faster than others.

“I’m a little obsessive about it,” Buescher admitted.

“I grew up in Missoula, and when I was about 13, my brother challenged me to ride every street in town,” he said. “I was too young to work and too old to be in the house all the time. We had a large family and apparently I had a lot of energy to burn off. When I was 15, they encouraged me to ride the tour.

“I rode the first one the way all kids rode in 1976 — in jean shorts, tennis shoes and a T-shirt. We camped at Seeley Lake, and I remember we had some Icy Hot (topical pain reliever) to put on our legs. I’m a freshman in high school, so I’m thinking that if it feels good on my legs, it would probably do wonders for where I was hurting the most — on the hot spots on my butt where my jeans were rubbing me raw.

“It burned so bad down there I had tears in my eyes, but I never told my friend what I’d done.”

Buescher has ridden TOSRV in bikes weighing as much as 30 pounds. His first “good” bike was a Raleigh Grand Prix 10-speed that cost $173.

Eleven bicycles later, he’ll ride this year’s event on a Specialized Tarmac that weighs only 17 pounds while still being strong enough to lug Buescher’s 195-pound frame. Cost: $5,500.

“Each year, technology helps me compensate for age,” he joked, adding that his old Brooks Pro (leather) saddle weighed 3½ pounds. This year he’ll perch on a Selle Italia SLR (carbon-titanium) saddle that weighs ¼ pound and cost nearly as much as his first bike.

Buescher’s wife, Jan Gerards, is a financial advisor who has an appreciation for the practical application of his biking passion. “It’s cheaper than a lot of hobbies people do,” she said, “and he recycles bike parts by making lamps out of them.”

Less vigorous diversions have been tempting, he said: “I was golfing for a while, starting to get pretty good, but I was getting so damned fat I had to decide where to put in my time, riding or golfing.”

His job with Northwest MedStar, a helicopter emergency response service, offers blocks of daylight off-hours that cater to a biker’s urge for the open road.

“But when I moved here, I told them at every job interview that I had to have the weekend after Mother’s Day off,” he said.

TOSRV has become the center of his early season biking universe, the goal that gets him out of bed on a less than pleasant day in March to catch the testosterone-charged group that rides from the South Hill most mornings before breakfast.

Last weekend, he pedaled the two-day Scenic Tour of the Kootenais Ride based out of Libby, but nothing quite stacks up to the tradition he started as a kid.

“I’ve seen TOSRV change over the years,” he said. “It used to be a loop ride, but they changed it to out-and-back from Missoula when (U.S.) Highway 93 got so busy and dangerous that riders were dropping out for safety reasons.”

Riding the same 115 miles from Missoula to Seeley Lake and back is surprisingly diverse even for a guy who’s pedaled down that road 29 times. “The scenery is totally different heading the other direction,” he said.

However, Buescher will always remember being on Highway 93 in the 1980 TOSRV when a huge dark cloud tumbled over the Bitterroot Mountains. Buescher was in college and his geology professor had been giving considerable emphasis to the rumblings of Mount St. Helens.

“So I knew immediately what was happening when the ash started coming down,” he said, noting that nowadays he occasionally heads to Longview, Wash., in June to ride the 82-mile Tour de Blast.

Many other weekend rides throughout the region have sprung up from TOSRV’s roots, but Buescher said the Missoulians On Bicycles, Inc., the group that sponsors TOSRV, still serves up the best food.

“It’s unsurpassed,” he said. “Great sandwiches and hot soup for lunches, a pancake breakfast feed, and the lemon bars on the third stop each day are what you ride for.”

Well, almost.

The lure of the ride is a complex combination of calories, camaraderie, endorphins and accomplishment. Spring mountain weather that might range from cold rain or light snow the first day to a scorching 80-some degrees the second day is part of the challenge.

Names come to mind for certain TOSRVs, such as the Hay Bale Ride. “That was the year a guy drove by our pace line near Ronan pulling a flatbed trailer loaded with hay,” Buescher recalled.

“He turned and two bales rolled off the trailer. They were spinning and rolling in our direction. They missed us, but a man riding behind us hit a bale dead center at full speed and it body-slammed him to the ground. Broke his clavicle.”

More than anything, the pace line itself has become the ride’s main attraction, owing in part to the day he and his three partners slept through their alarm at the Seeley Lake campground where many of the cyclists slept after the first day of riding.

“We woke and we were all that was left in what had been a sea of tents,” he said. “We threw our gear in the shuttle truck, got on our bikes and hammered past as many riders as we could. It was a rush.”

A road racer from Idaho saw the raw talent in Buescher and his high school buddies one year. “He whipped us into a rotating pace line and we felt like the U.S. Postal Team; we were flying!” Buescher said.

That’s the feeling he craves every year.

“We get a group — no more than seven or eight, otherwise it gets to be a Slinky and it’s dangerous. Everybody takes a pull in the front and then drops back in the draft.”

Like a well-oiled machine, they power down the road. “You just roll,” he said. “It’s really fun.

“If somebody wants to join us, we explain the rules. We use voice and hand signals to be safe.”

His fastest experience was the year his pace line was joined by his nephew, an Idaho state track champion.

“We averaged 22.9 mph,” he said, noting that they felt like human rockets. “Then we figured out that the riders in the Tour de France average 25 mph over 30 days in much more challenging terrain. It’s a humbling experience, but I love it.”