CIA, foreign agencies teaming up

WASHINGTON – The CIA has established joint operation centers in more than two dozen countries where U.S. and foreign intelligence officers work side-by-side to track and capture suspected terrorists and to destroy or penetrate their networks, according to current and former American and foreign intelligence officials.

The secret Counterterrorist Intelligence Centers are financed mostly by the agency and employ some of the best espionage technology the CIA has to offer, including secure communications gear, computers linked to the CIA’s central databases, and access to highly classified intercepts once shared only with the nation’s closest Western allies.

The Americans and their counterparts at the centers, known as CTICs, make daily decisions on when and how to apprehend suspects, whether to whisk them off to other countries for interrogation and detention, and how to disrupt al-Qaida’s logistical and financial support.

The network of centers reflects what has become the CIA’s central and most successful strategy in combating terrorism abroad: persuading and empowering foreign security services to help. Virtually every one of the more than 3,000 suspected terrorists captured or killed since Sept. 11, 2001, outside of Iraq came about as a result of foreign intelligence services working in tandem with the agency, the CIA deputy director of operations told a congressional committee in a closed-door session earlier this year.

The initial tip about where an al-Qaida figure is hiding may come from the CIA, but the actual operation to pick him up is usually organized by one of the joint centers and conducted by a local security service, with the CIA nowhere in sight. “The vast majority of successes involved our CTICs,” one former counterterrorism official said. “The boot that went through the door was foreign.”

The centers are also part of a fundamental, continuing shift in the CIA’s mission that began shortly after the 2001 attacks. No longer is the agency’s primary goal to recruit military attaches, diplomats and intelligence operatives to steal secrets from their own countries. Today’s CIA is desperately seeking ways to join forces with other governments it once reproached or ignored to undo a common enemy.

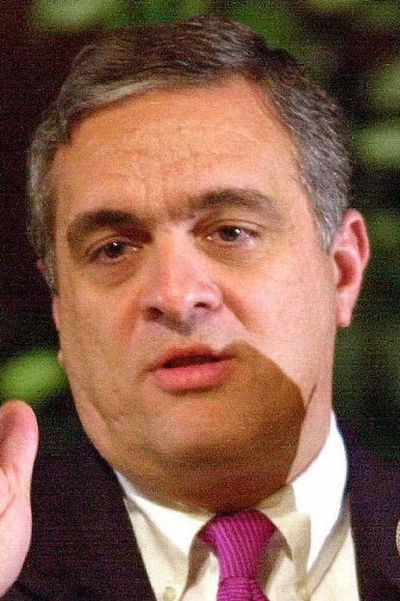

George Tenet orchestrated the shift during his tenure as CIA director, working with the agency’s station chiefs abroad and officers in the Counterterrorist Center at headquarters to bring about an exponential deepening of intelligence ties worldwide after Sept. 11.

Beneath the surface of visible diplomacy, the cooperative efforts, known as liaison relationships, are recasting U.S. dealings abroad.

The White House has stepped up its criticism of Uzbek President Islam Karimov in the past year for his authoritarian rule and repression of dissidents. But joint counterterrorism efforts with Tashkent continued until recently. In Indonesia, as the State Department doled out tiny amounts of assistance to the military when it made progress on corruption and human rights, the CIA was pouring money into Jakarta and developing intelligence ties there after years of tension. In Paris, as U.S.-French acrimony peaked over the Iraq invasion in 2003, the CIA and French intelligence services were creating the agency’s only multinational operations center and executing sting operations.

The CIA has operated the joint intelligence centers in Europe, the Middle East and Asia, according to current and former intelligence officials. In addition, the multinational center in Paris, codenamed Alliance Base, includes representatives from Britain, France, Germany, Canada and Australia.

“CTICs were a step forward in codifying, organizing liaison relationships that elsewhere would be more ad hoc,” a former CIA counterterrorism official said. “It’s one tool in the liaison tool kit.”

The CIA declined to comment for this article. The Washington Post interviewed more than two dozen current and former intelligence officials and more than a dozen senior foreign intelligence officials as well as diplomatic and congressional sources. Most of them spoke on the condition that they not be named because they are not authorized to speak publicly or because of the sensitive nature of the subject.

The CTICs are entirely separate from the covert prisons, known in classified documents as “black sites,” that the CIA has run at various times in eight countries. Legal experts and intelligence officials have said that the prisons – whose existence was disclosed in a Washington Post report earlier this month – would be considered illegal under the laws of several host countries. The CTICs, by contrast, are an expansion of the hidden intelligence cooperation that has been a staple of foreign policy for decades.