Unruly Saddam lectures judge as trial resumes

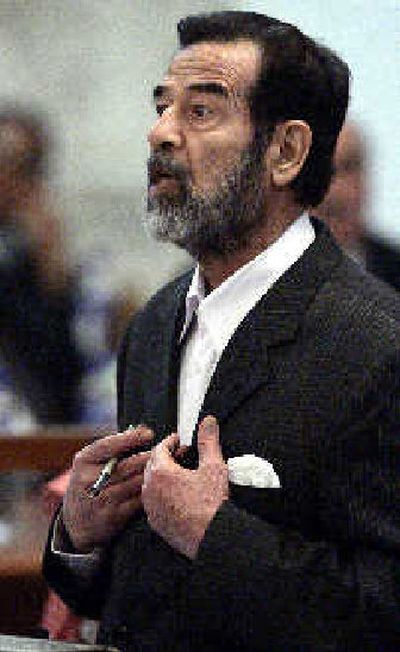

BAGHDAD, Iraq – One by one, they shuffled into the courtroom, once masters of Iraq, now broken men, standing trial for crimes against humanity and facing the gallows. Then came Saddam Hussein, swaggering, confident and combative.

His defiance appeared aimed at rallying his Sunni Arab supporters and distracting the court from the business at hand. After a brief hearing, the judge adjourned until next Monday – only 10 days before national parliamentary elections.

And rival Shiite politicians complained of the theatrics and the slow pace of a trial, which has completed only two sessions since it began last month.

The difference between Saddam and the seven other defendants was striking as the trial resumed after a five-week recess. The other defendants wore traditional Arab attire. Saddam looked immaculate in his black trousers and a gray jacket with a white handkerchief in the breast pocket.

Saddam acknowledged onlookers with a traditional Arabic greeting – “Peace be upon the people of peace” – as he took his place in the courtroom. He complained of having to walk up four flights of stairs in shackles, accompanied by “foreign guards,” because the elevator was not working.

The chief judge, Rizgar Mohammed Amin, assured him that he would tell police not to let that happen again.

“You are the chief judge,” Saddam snapped, speaking like a president to a subordinate. “I don’t want you to tell them. I want you to order them. They are in our country. You have the sovereignty. You are Iraqi, and they are foreigners and occupiers. They are invaders. You should order them.”

Saddam also complained that his pen and paper had been taken from him.

“How can a defendant defend himself if his pen was taken? Saddam Hussein’s pen and papers were taken. I don’t mean a white paper. There are papers downstairs that include my remarks in which I express my opinion,” he said.

Amin ordered bailiffs to give Saddam pen and paper.

Saddam’s combative manner seemed to inspire the others. At the end of the 2 1/2 -hour session, two other defendants spoke out, complaining of their treatment in detention or dissatisfaction with their court-appointed counsel.

The court’s tolerance of such comments drew sharp complaints from Shiite politicians who contend the tribunal is trying too hard to accommodate an ousted dictator who should have already been convicted and executed.

“The chief judge should be changed and replaced by someone who is strict and courageous,” said Shiite legislator Ali al-Adeeb, a senior official in Prime Minister Ibrahim al-Jaafari’s party.

The tribunal allowed former U.S. Attorney General Ramsey Clark and prominent lawyers from Qatar and Jordan to join the defense team as advisers, a move aimed at convincing foreign human rights groups that the trial would meet international standards of fairness.

Also, the chief judge ordered all handcuffs and shackles removed from the defendants before they entered the courtroom – another gesture toward the accused.

The defendants stand accused of killing more than 140 Shiite Muslims after an assassination attempt against Saddam in the Shiite town of Dujail in 1982. Convictions could bring a sentence of death by hanging.

None of the nearly 35 prosecution witnesses testified Monday, but the prosecution entered into evidence two videotapes – one shot in the aftermath of the assassination attempt showing Saddam in military uniform interrogating three villagers. The second was a videotaped statement by former intelligence officer Wadah Israel al-Sheik made last month shortly before he died of cancer.

Amin read the transcript as the tape played without sound. According to the transcript, al-Sheik, who appeared frail and sat in a wheelchair in a U.S.-controlled hospital, said about 400 people were detained after the assassination attempt, although he estimated only seven to 12 gunmen actively participated in the ambush of Saddam’s convoy.

“I don’t know why so many people were arrested,” al-Sheik said, adding that Saddam’s half brother and fellow defendant, Barazan Ibrahim, who was head of intelligence at the time, “was the one directly giving the orders.”

A day after the assassination attempt, whole families were rounded up and taken to Abu Ghraib prison, he said.

Al-Sheik noted that co-defendant Taha Yassin Ramadan, a former vice president, headed a committee that ordered orchards – the basis of Dujail’s livelihood – to be destroyed because they were used to conceal the assailants.

At the end of the session, Ibrahim complained he had not received proper medical treatment since being diagnosed with cancer and that this amounted to “indirect murder.” Defendant Awad al-Bandar said he and Saddam had been threatened in court last month. The judge told him to submit his complaints in writing.

Amin then adjourned the hearing so the defense could replace lawyers slain since the trial opened on Oct 19. Saddam’s personal attorney, Khalil al-Dulaimi, complained the defense needed at least a month. Amin suspended the hearing for 10 minutes to confer with the four other judges and then announced that the Monday date was firm.

The slow pace of the proceedings has angered many Iraqis – especially majority Shiites – who believe Saddam should have already been punished for his alleged crimes. Shiites and Kurds were heavily oppressed by Saddam’s Sunni Arab-dominated regime.

“Iraqis are beginning to feel frustrated,” said Ridha Jawad Taki, a senior official in the country’s biggest Shiite party. “The court should be more active. Saddam was captured two years ago. … The weakness of this court might affect the verdicts, and this is worrying us.”

However, Clark and others argue that a fair trial is impossible in Iraq because of the insurgency and because the country is effectively under foreign military occupation, despite U.S. and Iraqi assurances that the trial will conform to international standards.

On Monday, Clark told CNN it was “extremely difficult” to assure fairness in the trial “because the passions in the country are at a fever pitch.”

“How can you ask a witness to come in when there’s a death threat?” he asked. “Unless there’s protection for the defense, I don’t know how the trial can go forward.”

Clark, who was attorney general under President Lyndon Johnson, is a staunch anti-war advocate who met with Saddam days before the 2003 invasion. He has also consulted several times with one-time Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosevic, who is on trial in The Hague, Netherlands, on war crimes charges.

Nevertheless, the trial has unleashed passions at a time of rising tensions between the country’s Shiite and Sunni communities. Government security services are dominated by Shiites and Kurds, while Sunni Arabs form the backbone of the insurgency.

In Baghdad, Shiite businessman Saadoun Abdul-Hassan stayed home Monday to watch the trial on television but expressed disappointment over the pace.

“Saddam does not need witnesses or evidence. The mass graves are the biggest witness, and he should be executed in order for the security situation to improve,” he said.

In Saddam’s hometown of Tikrit, however, merchant Adnan Barzan called Saddam the “legitimate president” of Iraq and said that “those who speak about mass graves and about Dujail should go see what the new government is doing.”

“They will find real mass graves dug by this government and not by the government of Saddam Hussein,” Barzan said.