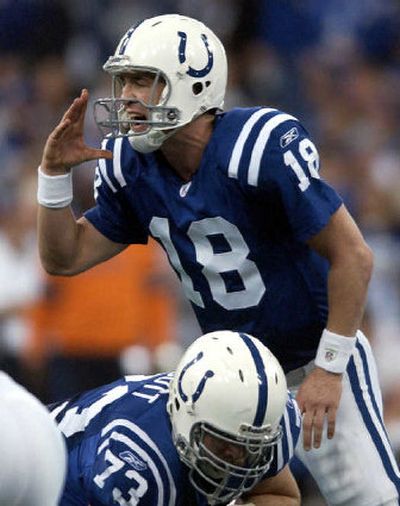

Is this the year for Manning?

INDIANAPOLIS – Peyton Manning would do anything to avoid discussing the New England Patriots or the Super Bowl.

He’d do even more to separate himself from the phrase “couldn’t win a championship.”

“Not being to a Super Bowl is something we’d like to change this year,” Manning said. “Our goal every year is to get a championship for Indy.”

The quarterback enters his eighth season determined to shed the Colts’ lingering legacy: an inability to get past the Patriots and win a Super Bowl.

It’s a heavy burden for Manning, a No. 1 pick who by nearly every measure west of New England is worth his $98 million contract.

In seven seasons, the Indianapolis Colts have gone from also-ran to perennial contender. They’ve been to the playoffs five times and reached the 2003 AFC championship game, and fans are now talking about title runs.

Manning has been the cornerstone of the rebuilding project. He produced a strong rookie season in 1998 and followed that with an NFL record 10-game turnaround in 1999. Last year, Manning set single-season records for touchdown passes (49) and quarterback rating (121.1) and extended his own league mark of consecutive 4,000-yard seasons to six.

He, Joe Montana and Brett Favre are the only players to win consecutive MVP awards, and many believe Manning could join Favre as the only three-time winner.

“Whenever I see him on TV, I stop and watch,” said Hall of Fame quarterback Dan Fouts, who never won a title with San Diego. “The things he does, the control he has and the way he executes that offense, there isn’t a team in the league that wouldn’t want him.”

But despite the seemingly flawless resume, Perfect Peyton is still dogged by the four dirtiest words in the Colts’ vocabulary: “New England” and “Super Bowl.”

At New England, he is 0-7, including crushing playoff losses in 2003 and 2004 when Manning was anything but perfect. He’ll get another chance Nov. 7, a Monday night game in Foxborough, Mass.

A victory over the Pats could change everything. The Colts expect to vie for home-field advantage in the playoffs, and if a win keeps them in the RCA Dome throughout January, Manning might finally have a shot at his elusive Super Bowl.

The key components in the offense, which produced the NFL’s first trio of 1,000-yard and 10-TD receivers, remains essentially intact. Coach Tony Dungy spent the offseason amassing more hitters on defense and more speed on special teams in hopes they could help beat the Patriots.

But once again, most of the attention will focus on Manning. The quarterback is accustomed to the scrutiny.

In high school, he endured the comparisons with his father, Archie, one of the beat quarterbacks in college football history and one of the NFL’s most talented QBs in the 1970s.

At the University of Tennessee, the younger Manning went 39-6 and set 33 school records, but was criticized because he couldn’t beat rival Florida.

When he entered the 1998 draft, the debate was whether Manning or Ryan Leaf would be the better pro. (Leaf, the No. 2 pick, fizzled and is out of football.)

Manning’s early NFL career was stigmatized by an 0-3 playoff record and questions about whether he could win a postseason game or beat the Tennessee Titans – until he did both in 2003.

Dungy believes it’s unfair to hold anyone to such a high standard.

“Say a quarterback has a 10-year career, only 10 quarterbacks could even win it,” Dungy said of the Super Bowl. “You’re always going to have quarterbacks who never get there and never win it, and I’ve seen some pretty good ones that never won it.”

For some, like Montana and Joe Namath, Super Bowl victories defined their place in history. For John Elway, it proved the culmination of an outstanding career.

But the Hall of Fame is littered with quarterbacks, from Y.A. Tittle to Dan Marino and Fran Tarkenton to Fouts, who never won a title.

Manning refuses to compare himself to players like Fouts or Marino yet because he contends he has many years left and still works incessantly to get better.