Wider Jewish outreach

The world used to be much smaller for Jewish groups trying to win Christian friends.

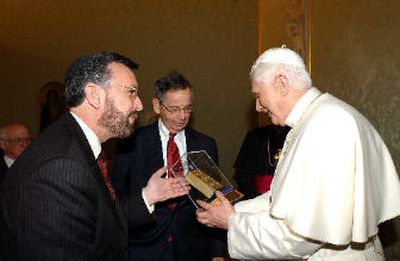

Interfaith relations once were a matter of Jewish leaders shaking hands at the Vatican, seeking out mainline Protestants in the United States and Europe, and forging ties with American evangelicals over Israel.

But the landscape of Christianity is transforming, creating a new challenge in the drive for mutual acceptance: Christian churches are growing fastest in the developing world and, within a generation or two, will eclipse their northern counterparts in size and influence.

The outlook of some of these churches is warm toward Judaism but still different than that of American and European Christians and will require an outreach strategy far broader than the one Jewish leaders adopted after the horrors of World War II.

“The balance in terms of influence is shifting southward,” says Rabbi David Rosen, who directs interfaith work internationally for the American Jewish Committee. “It’s certainly an issue we need to give much more attention to.”

The changes are not all negative. In Africa, where the Christian population grew from about 10 million to 423 million over the 20th century, many feel an affinity for Jews and Israel.

African Christians place a heavier emphasis on the Old Testament than northerners do, partly because they see in the sacred book a reflection of their modern-day suffering – from poverty to illness to moral corruption.

Jacob Olupona, a Harvard University expert on African religion, notes that many African Christians, including him, have Old Testament names.

Visiting Israel is so important to Nigerian Christians that many put “J.P.” – meaning “Jerusalem pilgrim” – at the end of their names after they travel to the Jewish state, just as Muslims who make the pilgrimage to Mecca add “al Hajj” to their names, Olupona notes.

“The African Christians see the Jewish land as sacred to them, too,” he says.

In Latin America, the situation is less promising.

Jewish leaders say the declaration of the Second Vatican Council four decades ago rejecting collective Jewish guilt for the death of Christ has not sunk in on the predominantly Roman Catholic southern continent.

Hispanics are bringing their views with them as they move to the United States in growing numbers, Jewish leaders say. About 28 percent of adult U.S. Catholics are Hispanic, and their presence in the church is increasing.

It’s “classic European anti-Semitism transported to Latin America,” says Abraham Foxman, head of the Anti-Defamation League, a Jewish civil rights group.

The shift is occurring at an already anxious time for Jewish groups.

The generation of Christian leaders who lived through the Holocaust and the creation of the state of Israel in 1948 is dying out. Pope Benedict XVI, a 79-year-old German, could be the last pontiff to directly experience the war.

Meanwhile, with the Catholic Church winning millions of new adherents in Africa and Asia, Vatican observers say it is only a matter of time before the church has its first Third World pope. The next wave of Christian leaders will have different concerns and may not view relations with Jews as a priority.

“The difficulty is, particularly in Africa and especially in Asia, there’s the sense that the Catholic issues regarding Jews are really European issues,” says Philip Cunningham, executive director of the Center for Christian-Jewish Learning at Boston College. “I think there is need to foster a consciousness that it’s more than that.”

Other potential troubles are looming.

Among them is a stream of Christian thought that focuses on the biblical message of freeing the oppressed. Its adherents across denominations worldwide tend to identify closely with Palestinians and have a negative view of Jews, Cunningham says.

Also, the fastest-growing wing of Christianity around the globe is Pentecostalism, a movement that has little contact with mainstream Jewish groups even in North America, where it originated. Leaders of the spirit-filled churches from Africa and Latin America are following immigrants from their homelands to the United States and are opening churches to serve them.

In Africa, the sometimes violent conflict between Muslims and Christians has generated some Christian sympathy for the plight of Israelis; Christians tend to see the two faiths as facing a common threat.

But Rosen says this trend is ultimately harmful since Jews and Christians must find ways to build ties with their Muslim neighbors.

The American Jewish Committee is trying to tackle the issue. It created a Latin America institute a year ago, has sent travel teams to China and recently started an Africa outreach effort.

Cunningham says Latin American Catholic bishops are aware of Hispanic anti-Semitism and have been making statements to fight it. And Jewish groups have been inviting Catholic cardinals from the developing world to visit U.S. Jewish seminaries and travel to Israel.

Rabbi James Rudin, who spent years leading the American Jewish Committee’s interfaith work, recalls that “people rolled their eyes” when he first argued that the agency should focus on the developing world.

Now, Rosen says: “We’re putting much more energy into it.”