Fashion statement

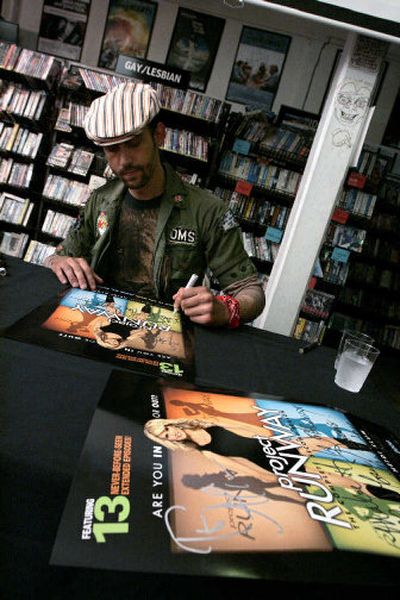

So, do you Runway? I do. “Project Runway,” the Bravo Network fashion industry reality show, is hot. And not just with teenage girls and haute-couture fashionistas. Even people like me, middle-class shoppers who buy off the rack, are hooked.

I don’t know how it happened. I hate reality TV. I don’t watch rich housewives get Botoxed in their designer kitchens in “The Real Housewives of Orange County.” I’m creeped out by the thought of watching anyone get tattooed on “Miami Ink.” I’m turned off by the idea of watching “Dog the Bounty Hunter” chase down bail-jumpers. I don’t want to watch men with huge biceps and tiny heads build motorcycles in “Orange County Choppers.” And I really don’t want to watch Hugh Heffner’s three favorite platinum-blonde playmates redecorate their rooms and share a limo with “Hef” in “The Girls Next Door.”

But I never miss an episode of “Project Runway.” Each Wednesday night my daughters and I pile onto my bed and settle in for the show.

For those of you who don’t know, “Project Runway,” now in its third season, is a reality show built around a group of people who want to be fashion designers.

After making it through the audition process, 15 designers vie for the grand prize. They are a diverse group, some young and hip, others middle-aged. Each brings a background in fashion design to the arena. At the end of the show the winner will receive $100,000 to start his or her own clothing line.

To be a part of “Project Runway,” you have to be able to sew; to design and construct a garment that fits the body and figure of the model assigned to you.

You have to grasp challenges given to you, and you have to meet the deadlines. Then, the finale of each episode is a full fashion show down the runway, where the garments are judged by super model Heidi Klum and top name designers like Michael Kors and Diane Von Furstenberg. The always sharp-tongued Nina Garcia, fashion editor at Elle Magazine, adds pointed commentary. At the end of the evening another designer bites the dust.

As silly as it sounds, it is all fascinating. And it’s not just for women.

My 19-year-old son, someone I would describe – with affection – as fashion challenged, has seen the show. He watches it on occasion.

I hear women talking about catching their husbands watching.

“Project Runway” is good TV.

I have my own reason for enjoying watching a room full of men and women scramble to meet a fashion challenge.

The only class I ever failed was my high school sewing class. My mother asked incredulously, raising her face to the heavens and waving her arms, “Who the heck fails sewing?”

In my high school in the late 1970s, the series of classes designed to send us out into the world equipped with the skills to feed ourselves, clothe ourselves and clean up after ourselves, was lumped into what was then known as “home economics.”

Home economics was taught by Mrs. Dognibini, (pronounced “Dough-bee-nee”) a dumpling-shaped, care-worn woman who bore the scars of years of teaching teenagers.

Mrs. Dognibini’s class was considered an easy way to fill a few credits for graduation, so it was usually packed with students who expected, and for the most part got, an easy ride.

The jocks huddled in the back of the room, making the girls squeal by slipping a needle and thread under the outermost layer of skin on their hands and stitching their fingers together.

The girls huddled around the table in the mock kitchen where we learned how to cook and set the table properly.

They gossiped and worked on their make-up (watching the boys in their compact mirrors) and hair, while the boys tossed balls of paper and caught them with their homemade catcher’s mitts.

And then there was me.

I was too shy to fit in with the girls who primped and preened, which was just as well. I wasn’t asked to join them.

In those days, I was petite and quiet and I blushed easily, so that made me a perfect target for the boys. They picked at me the way a cat plays with its prey. In self-defense, I hid behind my book.

The weary Mrs. Dognibini didn’t ask a lot of us. All you had to do to pass the course was complete a garment. We were taught, if we bothered to pay attention, how to follow a pattern and stitch together a simple elastic waist skirt. I don’t remember what the boys were supposed to make.

I wasn’t interested in sewing. Sewing was complicated. Threading the machine was complicated. I read. That’s why the deadline caught me off guard. Suddenly it was the night before our project was due. I had to have a skirt by morning.

Always resourceful, I dug through the bag of fabric scraps my mother kept and pulled out a length of corduroy. No time to look at a pattern. I just folded the fabric and stitched the two edges together.

Digging around a little more, I pulled out a piece of wide elastic that had been ripped off the waist of some discarded piece of clothing. It wasn’t the same color as the corduroy, but, hey, beggars can’t be choosers.

I stitched the elastic to the top of the fabric tube I’d sewn. Then I hemmed the skirt on the machine and cleverly disguised that fact by adding a piece of rickrack.

Finished! In a matter of minutes I had something like a skirt.

Well, not according to Mrs. Dognibini. The woman who had been numbed and beaten down by too many years of asking boys to unstitch their hands, and girls to stop curling their eyelashes; years of taking books away from bookworms hidden in the corner, came to life. She woke up the way, say, volcanoes wake up. There was a lot of noise and I really felt the heat.

“This,” she hissed, “Is not a skirt.”

I blinked at her, chewing my lip and rubbing the toe of one shoe against the calf of the other leg while she continued to blow her top.

“This is a zero,” she said, shaking the thing in my face. “If you make nothing out of nothing you get nothing.”

Oh.

Suddenly I wasn’t invisible anymore. Being skewered by the meek and mild Mrs. Dognibini, was good stuff. You could make it all the way through high school without seeing that happen. The entire class gave us both their full attention.

The furious little woman glared fiercely up at me, tossed the offending piece of material into the trash basket beside her battered oak desk, and then turned away.

I stood there a minute or two longer, shifting awkwardly, unsure of what to do.

It was over.

I shuffled back to my seat, whispers and sniggers followed my every move.

Then, a week later, when the year’s final report cards went home, I got to explain to my mother just how one managed to fail sewing.

Another volcano. More noise. More heat.

That’s why I love “Project Runway.” There is every bit as much drama as my high-school sewing class and, at least for me, it’s a lot more fun.

Each week, I watch people get their assignment and then sit down to their sewing machines. Their task, as Tim Gunn, the Chair of the Department of Fashion Design at Parsons The New School for Design in New York City, which is where the show is filmed, says in his soothing voice is to “Make it work,” and then “Carry on.”

That’s good stuff, too.

Unlike most reality shows, there isn’t any sexual intrigue or excruciatingly personal information exposed on “Project Runway.” There’s too much work to do. There isn’t time for that kind of fooling around.

Oh, there’s plenty of salty language, carefully bleeped out, a lot of dirty looks and – as the competition heats up – some backstabbing.

But the work never stops.

The designers are focused because it matters to them to get it right. They know that if you take something, and you make something, you’ve got something.

I could have saved myself some embarrassment and learned that lesson years ago, but I didn’t.

That’s why I Runway.